By the time the next president enters the Oval Office, U.S. airlines could be flying regularly scheduled flights to Cuba, a result of President Barack Obama‘s detente with the island. American businesses are eager to invest. U.S. citizens are already making more tourist trips to the island and Cuban-Americans are free to send more money to their relatives.

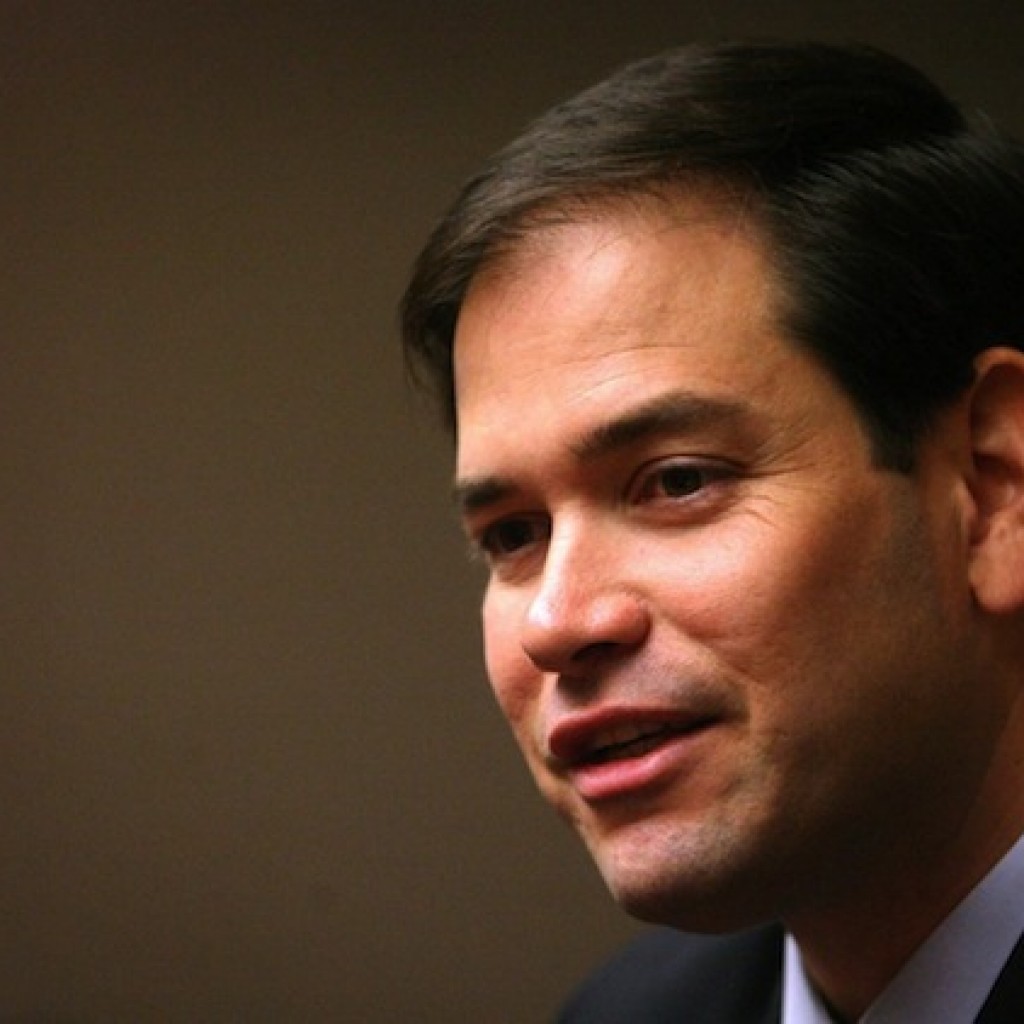

Politicians are sometimes loath to make policy changes that take rights away from people. But Marco Rubio says he has no qualms about fully rolling back the opening set in motion by Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro – Fidel‘s 84-year-old brother – about a year ago.

He also thinks U.S. business people tantalized by the prospect of investing in the island will change their minds after the reality of dealing with the Castro government sets in. Cuban law generally prohibits majority foreign ownership of businesses on the island, although it allows joint ventures with the government and has allowed majority ownership in a new free trade zone.

“American companies think they want to invest in Cuba,” Rubio said. “They have no idea what the terms are. The terms are, they don’t own anything. You can’t go to Cuba and open a business and own it.”

He applies a similar theory to public opinion polls finding most Americans support Obama’s opening with Cuba. Most poll respondents “are just giving their opinion on an issue that they really don’t pay attention to,” Rubio said. “I think when you present to people the reality, those numbers begin to change.”

Cuba has released some political prisoners as part of the detente and made some changes favored by businesses. Rubio sees those changes as largely cosmetic and says Obama essentially gave the Castros a financial lifeline to maintain their power and possibly entrench the current system after the brothers die.

While Rubio agrees with little Obama has done in office, he pointed to the president’s diplomatic opening with Myanmar, also known as Burma, as a more effective model for dealing with authoritarian governments. After years of estrangement, the U.S. restored full diplomatic relations with Myanmar after the country’s leaders made a series of sweeping economic and political changes, including a transition from military rule to a quasi-civilian government.

This month Myanmar took another step forward by electing a fully civilian government for the first time, with opposition hero Aung San Suu Kyi‘s party emerging victorious.

“I’m not telling you what’s happened with Burma is perfect,” Rubio said. “But even that opening came with some elements of democratic opening that allowed opposition groups and forces and ideas to enter the political marketplace.”

“Nothing was asked of Cuba,” Rubio said.

To the White House and supporters of Obama’s opening with Cuba, Rubio is living in the past. Fifty years of hostilities did nothing to push the Castros from power and Obama administration officials say there’s no indication that sticking with the same policy will suddenly achieve that outcome.

Rubio knows his hard-line views on Cuba are also competing against a surge of public interest in the island. Even with continued travel restrictions, Americans are flocking to Cuba in record numbers for modern times. The island has attracted the occasional vacationing celebrity and plenty of U.S. media attention.

Rubio says he shares the curiosity with Cuba. He enjoys watching the television show “Cuban Chrome,” which explores how people keep decades-old American cars running even though spare parts are hard to come by under the U.S. embargo. And he wants to go to the island one day and see the cemetery where his relatives are buried and the farmlands his grandfather told him about as a boy.

“It’s all very interesting,” Rubio said. “My problem is when people come back and say, ‘I visited Cuba and it’s a wonderful place, the people are happy, the government is great.’ That’s what I mind.”

Republished with permission of The Associated Press.