The streak survives.

For the 10th year running, Florida dodged a hurricane, setting a new record, while the rest of the eastern seaboard escaped a hit by a major hurricane. It helped that the 2015 season – four hurricanes, a depression and seven tropical storms, including one that triggered a state of emergency across Florida – largely followed the preseason playbook that called for fewer storms thanks to a powerful El Niño weather pattern heating up the Pacific.

Elsewhere was a different story. More than 40 people died at sea, including 33 aboard the El Faro, a 790-foot cargo ship that sailed into a fierce storm as it swelled to Category 3 strength in just six hours. On the tiny island of Dominica, at least 30 people were killed in lethal mudslides.

Whether the lengthy quiet stretch signals an end to an era of bustling storm production that began in 1995, or was simply a factor of the El Niño, remains to be seen. Whatever the case, fewer storms have little to do with the streak.

“Just because we’ve had a good string of luck doesn’t mean it’s going to continue the next year,” said Michael Brennan, a senior hurricane specialist at the National Hurricane Center. “Storms go where they’re going to go.”

The season got off to an early start with a preseason opener that hinted at some of the unpredictability to come.

On May 7, Tropical Storm Ana formed off the coast of South Carolina, becoming the earliest storm to ever make landfall, Brennan said. The storm caused minor damage as it trekked across three states before fizzling off the coast of Massachusetts.

Bill and Claudette followed in June and July, nearly exactly a month apart. Both were short-lived. But while Claudette remained far off the coast of New England, Bill, which formed in the Gulf of Mexico, rolled across Texas, triggering heavy rain, tornadoes and flooding blamed for two deaths.

In late August, Danny became the first hurricane of the season and quickly grew to a Cat 3 before shifting atmospheric winds – called wind shear – killed it.

Although forecasters had predicted the El Niño-fueled wind shear would keep storms from intensifying, in the Caribbean those winds turned out to be even greater than expected, said Phil Klotzbach, a research scientist at Colorado State University’s Department of Atmospheric Science who works with William Gray, one of the first scientists to identify the phenomenon of wind shear.

The El Niño, which forecasters initially thought might lose steam over the summer, has instead shaped up to be one of the strongest on record, and certainly since the last powerful event in 1998 that fueled bad weather across the world linked to an estimated 23,000 deaths and $35 billion in damage.

“In mid-August through early September, we had whole pile of storms and then they just died in the middle of the ocean,” Klotzback said. “That usually doesn’t happen. They hit land or head north and die over cold water. But with the strong shear, when they approached the islands, they just got sheared to death.”

The storms didn’t always cooperate.

In late August, Erika formed nearly a thousand miles east of the Leeward Islands and spent the next five days vexing forecasters. As it churned across the Atlantic, Erika produced a cone of uncertainty that was nearly as uncertain as the storm itself, with shifting conditions pointing the storm in different directions.

Forecasters say weak storms can often prove the trickiest to predict because they can potentially strengthen and come under the influence of different atmospheric conditions.

With Erika, forecasters repeatedly warned the storm could take one course under one set of conditions and another if the storm strengthened. Computer models, which crunch huge amounts of data and typically help sort out the scenarios, were no help. The models kept coming up with different outcomes.

Fearful that a storm would catch residents off-guard after such a long quiet stretch, Florida declared a state of emergency and repeatedly urged resident to make storm plans.

Eventually, Erika broke up as it passed over Hispaniola. But not before dumping heavy rain across the Caribbean, triggering mudslides made worse by a regional drought. In addition to the deaths on Dominica, another four people died in Haiti.

A day after Erika fizzled, Fred popped up off the coast of Africa and became the first ever hurricane to form so far east, Brennan said. For the first time, the hurricane center issued a hurricane warning for the Cape Verde Islands. While maximum winds reached just 85 mph, middling strength for a Cat 1 storm, Fred still killed nine fishermen in a region unaccustomed to hurricanes.

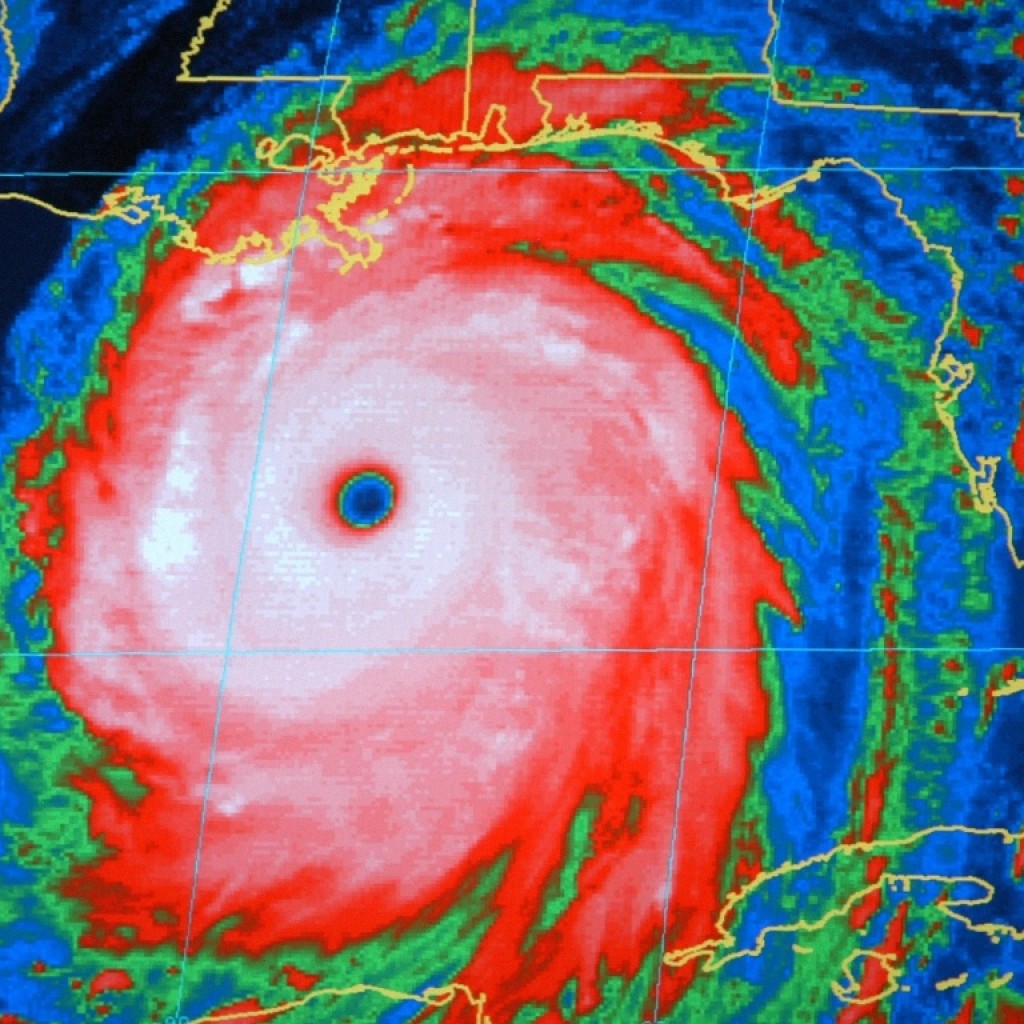

Over the next three weeks, wind shear mostly kept storms in check. Then came Joaquin, becoming what Klotzbach called a “wild card.”

After forming northeast of the Bahamas, Joaquin moved south and stalled, normally a death move for a storm because its mixing winds usually churn up cold water from deeper in the ocean, weakening the system. But around the Caribbean, where water temperatures this year were at record highs, warm water was also deeper than usual.

“It’s one of few areas where a hurricane can stall and not die very quickly,” he said.

In just six hours, Joaquin grew from a tropical storm to a fierce Cat 3 hurricane. Eventually it neared Cat 5 strength with winds reaching 155 mph.

For two days, the storm pounded parts of the Bahamas. Flooding cut off some islands, leaving residents short of clean water and food, while high winds ripped off roofs and downed trees and power lines.

Despite warnings from the hurricane center that Joaquin was a dangerous storm likely to grow, the El Faro set sail from Jacksonville, taking a path that put it and its crew of 33 on a collision course with the powerful storm. On Oct. 1, as Joaquin whipped up 120 mph winds about 10 miles north of uninhabited Samana Cays in the southern Bahamas, the El Faro sat powerless about 35 miles from its eye. At 7:30, the U.S. Coast Guard received a distress call reporting the ship had lost propulsion, taken on water and was listing about 15 degrees.

A heavy-duty HC-130 was launched to find the ship, but fierce winds hampered the search. Efforts to reach the ship by two hurricane hunter planes also failed.

The first sign of the ship came three days later when searchers found an El Faro life ring. Eventually rescuers discovered a body in a survival suit. Hoping to find others, rescuers radioed for a nearby cutter to pick up the body and moved on. By the time the cutter arrived, the body had disappeared.

The National Transportation Safety Board, which launched an investigation five days after the ship disappeared, finally located its hull sitting upright and largely intact on the ocean floor 15,000 feet deep. Searchers deployed an unmanned submarine to inspect the wreck and found that the bridge and the deck below it had been ripped from the hull. Also missing were the mast and its base, where the ship’s black box was mounted. In addition to navigation data, the black box would have recorded the crew’s conversations from the bridge possibly providing critical clues to the final moments aboard the ship.

Earlier this month, searchers finally located the bridge, but not the black box. They looked for five more days before giving up.

Without Joaquin, the 2015 season would have gone down as one of the mildest on record. But factored into the mix, forecasters say the storm accounted for half the power of the entire season, showing once again that the number of storms forecast is little comfort in the face of one big storm.

“We’ve been exceptionally lucky for a long period of time,” Brennan said. “But you can’t count on that to continue.”

Republished with permission of the Associated Press.