When NASA officials refer to their singular human-spaceflight program “Journey To Mars,” they’re not talking about the 800 to 1,000 days it will take for astronauts to get there and back.

At Kennedy Space Center, indeed all of Cape Canaveral, and worldwide for that matter, spaceflight and human-spaceflight facilities and organizations are incubating private, commercial-space programs to get to and do anything in Earth’s lower orbit and perhaps beyond. For NASA, that’s an intentional redirection, taking all of that off NASA’s plate, and allowing America’s official human spaceflight program to focus almost all it has on Mars now.

NASA’s Journey To Mars already is well underway, as far as space agency officials are concerned. This is it.

It’s a 20-plus year journey that NASA is undertaking, through science and technology advances, experimentation, baby-steps in space, funding, bureaucracy and politics. At the far end, the space agency, which not too long ago was rocketing astronauts into space several times a year, is focusing its human spaceflight efforts only on a mission likely to take place in 2035 or later.

Like any 20-year journey, NASA is proceeding largely on faith.

That’s because much of the science and many of the technologies the agency needs are not yet mature; only some of the spacecraft and support vehicles and hardware it needs are even under design let alone built, and even those built are not adequately tested; and because no one knows what politics and federal funding will look like even next year, let alone for each of the next 20 years running.

“There’s been a lot of excitement about ‘The Martian’ movie. It looks pretty easy in the movie…. But it’s not real,” Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA’s associate administrator for Human Exploration and Operations, said at a recent briefing on The Journey To Mars.

“This Mars mission is a huge, huge, challenge, and it is not like what you see in the movie, and it is not like what people are talking about,” Gerstenmaier continued, in his address to the Human Exploration and Operations Committee of the NASA Advisory Council. “We have a ton of preparation. We have a ton of work to get done to be ready to do this. It is not going to happen quickly, but it can be done methodically.”

That requires consistent federal funding that already has totaled billions of dollars and will require tens of billions more. It requires steady and reliable science and technology development through a myriad of independent efforts. There is no “Mars mission” budget line. The agency filters money through numerous budget lines, each of which can be cut or expanded, forcing the agency to reshuffle priorities.

And not everyone thinks this journey will go anywhere.

Among skeptics, George Abbey questions the funding, political backing, overall plan and hardware. He’s a senior fellow in space policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute in Houston, after having served in NASA for 37 years, the last five as director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

“There is no credibility to their program because they have no way to do it,” Abbey said.

He was a big proponent of the space shuttle program. Since it was retired in 2011, Abbey pointed out that NASA has no vehicles capable of accommodating assembly of big objects, like space stations or Mars vehicles, in space. Such capabilities, he said, cannot be replicated by the capsules NASA has or has planned.

But it’s more than that. NASA already is seeing delays and cost overruns on the rocket and capsule it’s planning to use to go to Mars, he said, and it has no fixed funding for all it will need.

“You don’t have the budget to do anything at this point,” Abbey said.

He’d prefer to see NASA go back to the moon, and said everyone else, the Russians, Europeans and Chinese, also are looking at going to the moon.

“Anyone who thinks going to Mars is going to be an easily task really doesn’t understand,” he said.

Alan Stern is a former associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, now associate vice president of the Southwest Research Institute for the Space Science & Engineering Division. He remains involved in several NASA programs and planning committees – he was the principal investigator for last year’s New Horizons visit to Pluto – although he resigned his administrator’s role in 2008 in a dispute over Mars programs funding.

Stern is more confident, and not worried about NASA’s needs to develop technologies and hardware to get to Mars. NASA has the talent, he said; money and politics are the problems.

“I think NASA knows its greatest challenge is finding a political consensus to get the budget level needed to support this program,” he said.

University of Central Florida political scientist Roger Handberg has been studying space policy for 30 years, and said NASA will persevere, but much of its success will be decided politically.

None of this year’s presidential candidates [with the exception of U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz] has addressed the Mars mission in any depth or with any firm commitment, he said. Looking forward, NASA is not a priority for presidential politics, so they have no need to do so. Cruz chairs the Senate Subcommittee on Space, Science and Competitiveness and is a Texas Republican plugged into Johnson Space Center policy and needs. In November he gave an interview to the Orlando Sentinel in which he expressed strong support for the Mars mission. Otherwise, Handberg said, the candidates all talk about NASA in historical terms, about what how wonderful the Apollo mission was for the country, as Florida’s Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio did last week in a campaign stop in The Villages. But then they never mention NASA when they talk about budget or policy priorities.

And regardless of what any of the candidates might commit, 20 or more years is several presidential tenures, Handberg added.

“NASA is going to do what NASA has been forced to do since the end of Apollo: start a program on a wish and a prayer and one-year’s funding, and they’re going to have to scrap every year to keep it funded,” Handberg said. “If it’s a 20-year program, it could become a 25- or 30-year program. But their resolve is so strong they will continue.”

And even in the best of circumstances, nothing at NASA happens quickly.

“I don’t know why it takes us so long to do things, but it does,” Gerstenmaier said.

It is, after all, a government agency, and everything is pursued bureaucratically, one tiny step at a time. New ideas and technologies are potential distractions. Yet unexpected outcomes would require some start-overs or abandonment of projects. Gerstenmaier cautioned that none of those should be considered failures, because that’s what experimentation is all about. NASA also has strict protocols for addressing risk, especially in human spaceflight programs.

NASA’s Mars astronaut capsule, the Orion, is completed and has been launched once in a test. It performed flawlessly. But there is more development ahead to prepare it for Mars.

The agency’s Mars rocket, the Space Launch System is not completed, and behind schedule. When it is ready, it will be the most-powerful rocket ever built, surpassing the Saturn Vs that carried Apollo to the moon. Its launches from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center, starting with an unmanned test launch of an Orion, perhaps as soon as 2018, will be spectacles not seen in more than a generation.

Numerous other components, including a human habitat module for the spacecraft [astronauts can’t spent the nine-month trip just sitting in the Orion] and habitats for the Martian surface, are no where near ready to be developed and not funded.

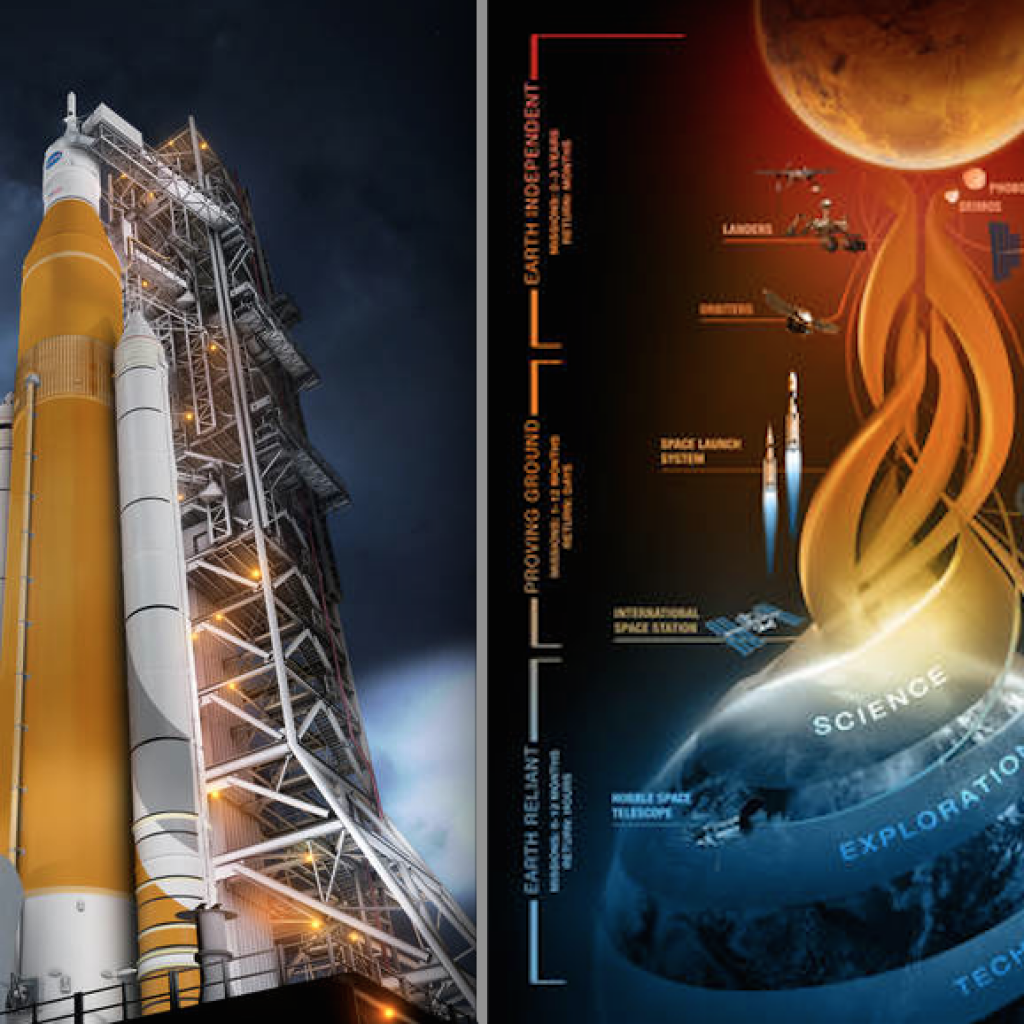

NASA’s plans essentially call for planning and building all the systems on Earth, doing research and development on them aboard the International Space Station, and proving them in three or four short SLS/Orion missions into cisunar orbit, the region of space out near the moon that NASA is calling its “proving ground.”

Then NASA wants more warmup missions somewhere beyond the proving ground. The first ‘somewhere’ is currently planned to be an asteroid, probably no sooner than 2025, and even that mission is being contemplated only as a research trip to prepare for Mars. It’s part of the journey. And it’s controversial, with plenty of time and potential for it to be scrubbed in favor of something else, such as a new moon mission.

Martian orbiters and more Martian landers have to be sent up to study the red planet. A few years prior to an actual human trip, SLS rockets must start transporting tons of buildings, equipment and supplies, some of it to Mars and some of it to space stations that would be developed along the way, in Martian orbit and perhaps in cislunar orbit. Most of that is no where near planned.

And much of the return trip, including needs for fuel, oxygen, water, etc., is largely only in concept stages right now.

This year NASA is planning its timetables, and hopes to have them more concrete by this fall.

Late this year that probably will mean NASA will begin setting up its labs for detailed study of longterm human space ventures and other technologies. Those labs will be at the space station. And that means some tough decisions, because there is a finite amount of room there, so something up there now, and plans for other experimentation, are going to have to go, Gerstenmaier said.

The space station’s life has just been extended to 2024, with the new budget. Is that enough? Gerstenmaier said that discussion will have to be had another day.

As for Mars, it’s a long ways away.

Yet unlike almost anything NASA has done since Apollo, a Journey To Mars has real potential to excite. Handberg called it a true history-making mission, the first since Apollo.

And that’s where NASA is focusing its human-spaceflight mission.

“The agency wants to send humans to Mars. It has the talent to do it, and the capability to do it,” Stern said. “I think if the United States backs NASA, we would inspire the world in ways you can’t even imagine.”