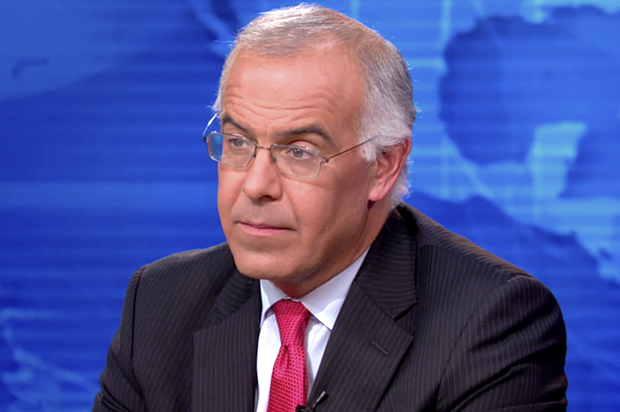

With his twice-weekly forum on The New York Times Op-Ed page, along with weekly gigs on NPR’s All Things Considered and the PBS NewsHour, David Brooks is regarded as one of the pre-eminent political pundits in the country.

So when I had the opportunity to speak with him about an hour-and-a-half before his scheduled appearance at the Palladium in St. Petersburg Wednesday evening, I asked him what he thought the greatest challenge facing the U.S. in 2016.

He believes it’s our increasing social isolation, something that was reflected in a column he wrote earlier this week, titled, “Dignity and Sadness in the Working Class.”

“The number of people who have five or six friends is dropping, the number of people involved in community organizations is dropping, the number of people who are in marriages is dropping, the number of people who are chronically lonely is increasing,” he said while speaking in an anteroom inside the Palladium.

“And so all the little web of connections that make up normal happy lives is fraying for a lot of people, and they’re falling between the cracks. And when they fall between the cracks, that leads to opiates, that leads to spiking suicide rates which are showing up, that leads to higher mortality rates, obesity rates … and so, it’s really the loss of connection.”

The 55-year-old Brooks has been traveling the country extensively over the past seven months, talking to an audience of hundreds who paid $65 to hear him about speak at the Palladium behind the publication of his latest book, “The Road to Character.” (Proceeds from Wednesday night’s event went to the St. Petersburg College Foundation).

In his recent travels, he says he’s found a level of disaffection among Donald Trump supporters that revolve around a sense of loss, adding that these Trump voters “tend to be richer people in poorer places.”

“The average Trump voter is making $74,000 a year,” he says, noting that’s not a bad salary outside some of our biggest cities. “They feel that they’re playing by the rules, but (feel) that a lot of people are getting off scot-free and aren’t playing by the rules. And then there’s just this overwhelming pessimism, and nostalgia, that things were one way, and now are they’re sliding downhill, and they’re sliding away from us.”

Brooks is dismissive of critics who say that his paper and the mass media, in general, haven’t been hard enough on the Manhattan real estate mogul turned GOP presidential nominee.

“We’ve written 8 million pieces criticizing his university, his charity and on the Op-Ed page, have we ever wrote a pro-Trump thing?” he asks rhetorically. “People are upset that Trump is still doing fine, so they have to blame somebody, so they blame the media.”

He mocks the notion that “if you just wrote that one piece, it will turn it all around. That’s not the problem here, ” referring specifically to a series of stories written over the past month by Washington Post reporter David Fahrenthold about Trump’s charitable foundation.

The biggest revelation there has been that Trump spent more than $250,000 from his charitable foundation to settle lawsuits for his businesses.

Earlier this summer, Brooks wrote that if the campaign remained static, Trump would probably end up getting somewhere between 38 percent to 44 percent support in the general election, unless he somehow could fuse a right-left hybrid populist movement together.

But with less than seven weeks to go before the general election, there’s no indication he’s done that, yet polls show him remaining extremely competitive in his race against Hillary Clinton in the fall.

“I think for the long term if there’s going to be a populist movement it has to cross the color line, he has to get some African-American support, and he certainly hasn’t done that,” he admits.

Brooks also notes that what is new about this election cycle is that college educated voters used to split in a general election roughly 50-50, but not this year.

“I spend a lot of time with businessmen, and they talk like Democrats now,” Brooks says. “They were sort of socially moderate, fiscally conservative but they’re for trade, and they’re for immigration. And I think those people are going to end up as Democrats, especially because they’re hanging around New York or Boston. And they look across at the Republican Party, and they see Trump and they say, ‘well that’s not me.’

“And so, I do think that that the professional class is going to migrate over to one party, and the nonprofessional class is going to migrate to the other — with the exception of race, that’s the barrier — but I think that’s where things are headed.”

Brooks thinks U.S. politics are changing, with the divide more with the professional classes who likes the forces of globalization, trade and immigration versus those who don’t. “It’s new battle lines, and it’s not the old debate between big government versus small government anymore.”

Like any publicly famous social commentator, Brooks has his critics on the left and the right. He was considered the “house conservative” when he began writing columns for the Times in 2003, but has been known to disappoint fellow travelers often over the years.

He has come down recently against San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick‘s refusal to stand for the national anthem to protest racial inequality and oppression in the U.S. — an issue that has catapulted the 28-year-old football player on the cover of this weeks’ Time magazine.

Brooks’ negative take elicited more than a thousand responses to the Times website before it stopped accepting comments. In asking him about the column, it’s obvious he stands strongly behind the piece.

“I would just say that there are a few things that bind us; there are a lot of things that divide us, racial experiences and class experiences, but there are also a few things that unite us, and one of them is the national anthem, the Pledge of Allegiance, our shared patriotism for the country, our shared gratitude for the people who gave us this country, and hopefully some shared belief in the ideals,” he says.

“And so I’m all for protesting the things that are disgraceful about the country, but I hate to do it in a way that tears at what is left of our unity, which is already so tattered and frayed. And I do think if you — the reason that Martin Luther King Jr. sang the national anthem and quoted the Declaration in his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech was because the ideals of the country are exactly what the solutions to the problems of the country, and so paying homage to those ideals gives you this awesome lever to fight against inequality,” he added.

“And so I would hate to throw away that lever, and I would hate to separate you from anybody else who’s also American, and frankly I hate to insult people who really get emotional about those things.”

Brooks has spoken and written extensively about Barack Obama since he came on the national scene and began running for president nearly a decade ago. He has no time for conservatives who say race relations have worsened since Obama’s election.

“I think he’s been sort of a role model in terms of his personal behavior,” he says. “It’s not like somebody from the Obama administration is going out and shooting people in the streets … so the causes that are really inflaming us are not related to the president.”

“I think he may regret later in life he didn’t spend more time in his administration working on the plight of African-American men in particular, that more resources weren’t thrown at that problem and so I think that’s something he’ll probably do post-presidency. Some of the incarceration stuff, there was grounds for more work on that or just people coming out of prison, or inner city boys growing up in single parents’ households.

“I think a lot of work needs to be done there, and I think he’ll regret that he didn’t do more.”

New York Magazine once wrote that Brooks and Obama both “fetishize balance.” It wasn’t a compliment.

“I admire balance,” Brooks laughs when asked to comment on that comparison. “I think most political issues are competitors between partial truths and so mostly, on most issues both parties have a piece of the truth and I trying to balance those pieces is the heart of politics.”

Brooks has previously said that he’s more of a “3,000-word guy” whose challenge every week is to write 800-word columns, and says his worst columns come when he tries to “cram too much” into a piece. But he still enjoys writing them, and says he hopes to continue to pen them for at least another decade.

“It’s tremendous satisfaction having had your say, whether or not anybody listens, just to have the chance to say my piece, and the other nice thing — writing twice week it sounds easy but it’s hard to come up with ideas all the time, but it does keep your mind fresh … you’ve got to find something else that’s interesting, but you just gotta keep going. It does keep you learning stuff. It also keeps you forgetting stuff, because you go through so much (and) my memory is not good as it is.

“And another thing. I’m convinced something like my job will exist for another 10-15 years. The industry seems to be a little more stable than it did, and I’m hoping to do it if they’ll have me for another 10 years.”