Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum continues to make good on his promise to campaign in and compete for all 67 Florida counties during his campaign for governor.

Following up a well-received speech in Tampa, where he cautioned against a “Democrat lite” approach, Gillum hit Jacksonville on Sunday.

Jacksonville’s major challenge for Democrats: bridging the divide between various intraparty groups, including younger people inspired by Bernie Sanders and the older establishment types who reflexively backed Hillary Clinton a year ago in the presidential primary.

Finding a way to excite Democrats down-ballot locally has been tough for statewide candidates of late, despite a Democratic edge in party registration.

With that trend in mind, Gillum is smart to get going early.

Putting in the work in Jacksonville, including engaging young grassroots supporters, is key. And in Jacksonville, he found himself evangelizing for a brand of social justice absent from local politics and politicians.

It is a message activists have yearned to hear for a while now. And in Gillum, they have a ready exponent.

But the trouble comes in getting people to hear it. During a day in Jacksonville, Gillum made three stops and worked a national TV hit in. But he didn’t draw much local media interest.

For them, 2018 is remote. However, for Gillum – who regularly talks about his “18-month strategy,” – the time to launch and to get attention is now.

—

With that in mind, Gillum made many stops: the first at a popular Jacksonville church.

“I don’t know if we’re in a bad reality show or another season of 24,” Rudolph McKissick, Jr., the pastor of Bethel Baptist Church said about this “strange political season,” by way of introducing Gillum at the 7:45 a.m. service.

The pastor referenced VP Mike Pence and Gov. Rick Scott being in town Saturday, saying “the only thing that changes anything is a vote … seems like anytime we have the chance to shift things in the right direction, we don’t vote.”

“Anything I can do to get him elected the next governor of Florida, I will do,” the pastor said, noting Gillum’s family ties locally.

—

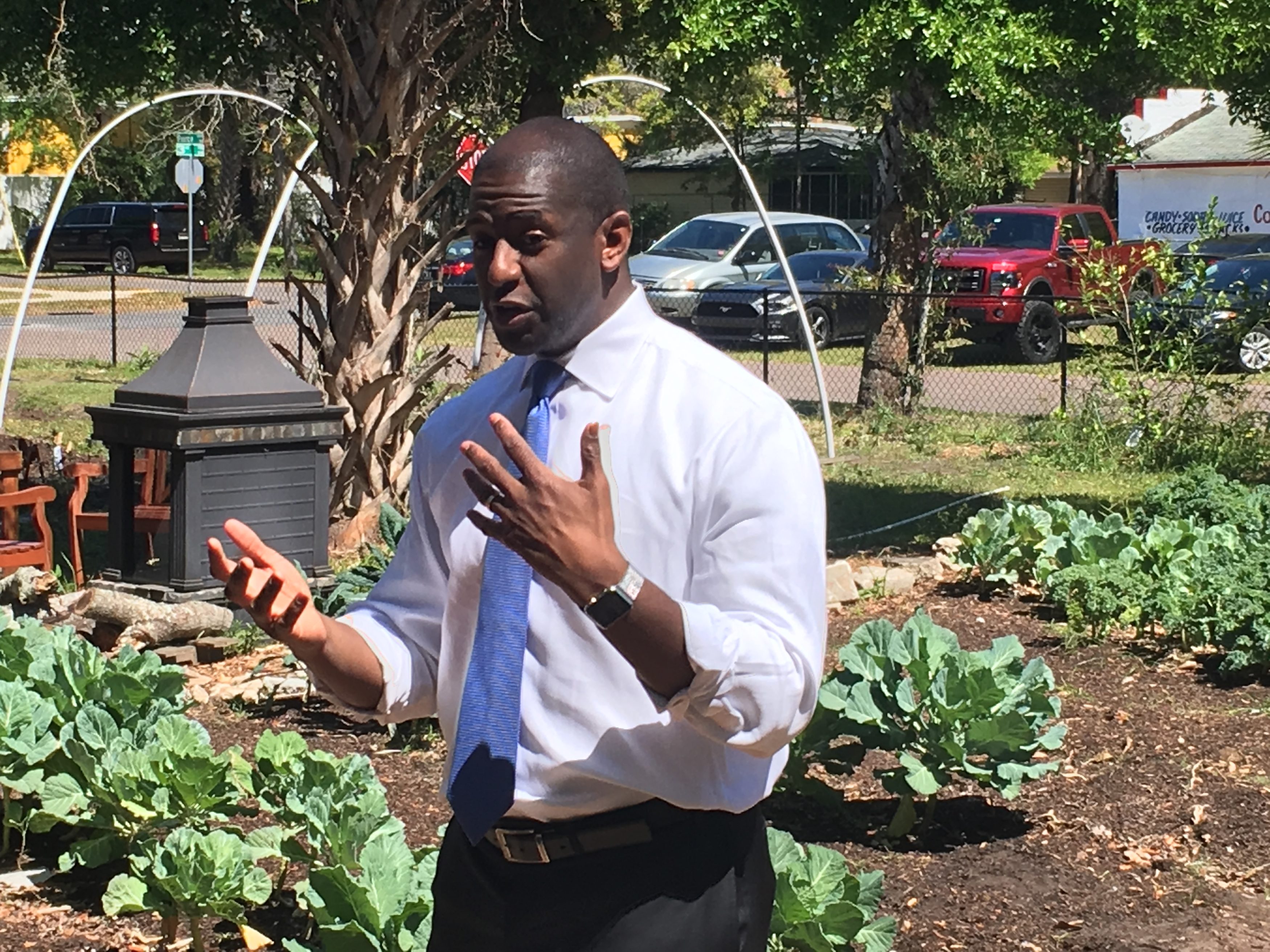

After a spot on MSNBC, Gillum’s next public stop was at the New Town Urban Farm near Edward Waters College.

The Urban Farm took an unused plot of land and turned it into a community garden – a real need in a food desert.

The land, founder Diallo-Sekou told us, was a vacant lot that had rubble in it previously.

The neighborhood is still transitional: an interesting backdrop to the speech was a pickup truck blaring Barry White as it trolled the block, with a sign on the side soliciting donations of clothes for military veterans.

But the Urban Farm is an oasis in the middle of an area always on the news for the wrong reasons, and it was an appropriate venue for Gillum talking about subjects at the heart of his appeal: finding ways to ensure that people have the leg up they need so they don’t end up a statistic.

“There’s a budget director in Washington, D.C. who said that there is no evidence that after school food assistance programs did anything to change the outcomes for kids,” Gillum said.

“That’s what I want as an educator: a hungry kid – attempting to get them to learn a lesson, understand, comprehend … if I’m that kid, and all of us have been there, if your stomach is growling, you can’t think of anything but the sound,” Gillum said.

His thirty-minute Q&A wasn’t one with applause lines or rah-rah moments: it was Obamaesque in its relating policy to real life for those in this state trapped by poverty and its myriad incapacitations and indignities.

Gillum spoke of a farm in his own youth, on his grandparents’ property in South Dade, where collards, squash, tomatoes, and fruit grew in a residential area.

“We lived off the land. Literally. In a place as urban as this, Miami-Dade, Florida. Here, you’ve got land and opportunity,” Gillum said, to do the same thing.

—

In much of Jacksonville, the physical hunger is palpable. But so too is the hunger for civil rights. Gillum addressed an issue close to his heart: the re-enfranchisement of the state’s 1.5 million who have lost their rights to vote.

“They paid their debt to society. Yet they come back into communities, and they still lack the ability to participate fully in our democracy. The majority of these individuals have committed crimes that are nonviolent – largely, drug-related crimes,” Gillum said.

“We cannot be tried twice for the same crime,” Gillum says. “Yet it seems you can be punished forever for having made a mistake.”

In addition to the vote, re-entry, such as through Ban the Box, is a Gillum priority.

And it’s personal.

“I’ve got brothers who have lost their rights. They’ve committed wrongs, and they have to pay the penalty for that. When they got back out and started trying to reintegrate into society, it was very difficult for them to find a job,” Gillum said.

“I’ve got some real entrepreneurial brothers. But actually, it’s survival. If they had a choice, they’d probably be working somewhere with somebody making a decent, honorable wage to take care of themselves and their families. But because door after door after door got shut to them, they had to create a way for themselves,” Gillum said.

“And that meant, for my brother Chuck who lives here in town, opening up a carwash. And going around with his mobile detailing unit and power-washing businesses and cars and sidewalks, and hiring other former felons,” Gillum said, emotion driving his voice.

Then he dialed it back.

“I think it’s a no-brainer … felon re-enfranchisement … to democratize those brothers and sisters,” Gillum said.

—

Leaving the Urban Farm behind, Gillum’s next stop was a fundraiser/meet-and-greet at a downtown art gallery 3 miles away.

A different venue and largely a different crowd.

Gillum smiled and posed for selfies, looking relaxed, as people like Sen. Tony Hill and other local political types mixed and mingled.

There was no charity truck blasting slow jams inside the gallery space. However, wine was available.

The key to Gillum’s viability is going to be bridging environments like the Urban Farm with the fundraising circuit, succeeding in both spheres – especially while he’s the most prominent Democrat in the race.

And, before it’s too late, ensuring that local market media in the state is paying attention to his message.