Woodrow Wilson was more focused on the end of World War I than a flu virus that was making its way around the globe, ultimately sickening hundreds of thousands of Americans, including the President himself.

George W. Bush stood with a bullhorn on a pile of rubble after the 9/11 attacks on lower Manhattan and promised that the people who were responsible “will hear all of us soon.”

Barack Obama was in office for just a few months when the first reports came in about the H1N1 virus, which would eventually be declared a pandemic like today’s new coronavirus.

Most American presidents will confront a crisis — or crises — before they leave office, whether it is a natural disaster, war, economic downturn, public health threat or terrorism.

What matters is how they respond, historians say.

“The number one thing a president can do in a moment like this is try to calm the nation,” said Julian Zelizer, a presidential historian at Princeton University.

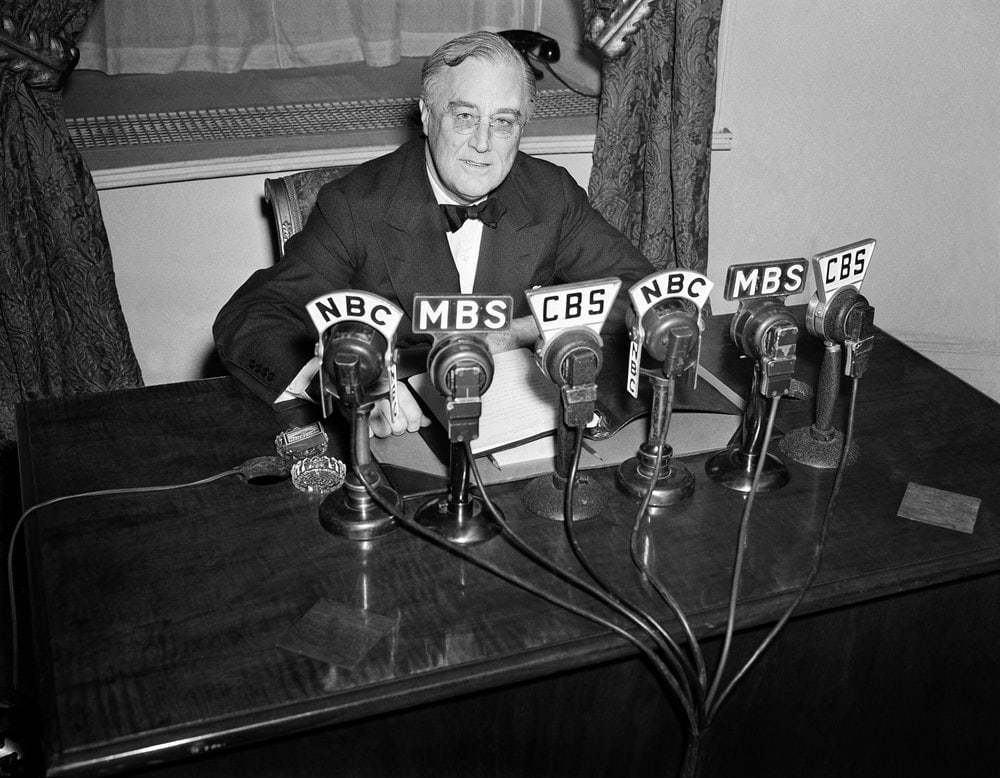

It’s what Franklin D. Roosevelt did during an extraordinary 12 years in office, guiding the nation through a bleak period of Depression-era unemployment, a severe Midwest drought known as the Dust Bowl and battle against the Nazis and Japanese in World War II.

During the influenza of Wilson’s time, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, including about 675,000 in America, presidents were not involved in public health issues in the same way that President Donald Trump has become engrossed in the U.S. effort against the new coronavirus.

Such issues were left for public health professionals at the state and local level.

“Wilson never issued any public statement whatsoever,” said John M. Barry, author of “The Great Influenza,” a book about the 1918 flu. “He was entirely focused on the war. Period.”

In fact, Wilson was so focused on the postwar peace talks that he was a party to in Paris that he, too, ended up stricken with the flu. He recovered.

Trump, on the other hand, seems intent on being the public face of the effort against what has become his most serious challenge in a reelection year. Trump, who has no scientific or medical training, now leads a daily White House briefing on coronavirus efforts by a task force he tapped the vice president to lead.

Trump styles himself as a “wartime president” fighting an “invisible enemy” responsible for hundreds of deaths and thousands of infections in the U.S. — numbers that will continue to rise as the virus spreads — and a dramatic upheaval of everyday life.

Millions of people have been ordered or urged to stay home for the foreseeable future, cut off from simple pleasures like going to restaurants, shopping malls or movies in a bid to slow the virus.

But Trump’s crisis management has earned mixed reviews, with praise from many supporters and criticism from detractors, including mayors and governors who are desperate for Trump to more robustly use his authority to help them get much-needed protective gear and supplies for doctors and nurses.

The president’s early attempts to minimize the severity of the situation, and to suggest that it was under control, have been panned, though he recently adopted a more urgent tone.

But the damage has been done, said Scott Morrison, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, citing lack of public trust due to Trump’s early handling of the situation.

“Not having trust and confidence is a huge liability heading into something this catastrophic,” said Morrison, senior vice president and director of the Global Health Policy Center at CSIS.

Obama was a few months into his first term in 2009 term when reports started coming in that April about the H1N1 flu. He addressed the situation that month, assembled a team and ultimately declared both a public health emergency and a national emergency to deal with the threat.

“This is obviously a very serious situation, and every American should know that their entire government is taking the utmost precautions and preparations,” Obama said as he opened a White House news conference that month.

He said public health officials had recommended that schools with confirmed cases consider temporarily closing, and that he had asked Congress for $1.5 billion in emergency funding to help monitor and track the virus, and to build a supply of antiviral drugs and other equipment.

“Everyone should rest assured that this government is prepared to do whatever it takes to control the impact of this virus,” Obama said.

Dr. Howard Markel, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for the History of Medicine, said Obama was “very hands on” during H1N1 — but not as visibly as Trump. Obama’s director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted daily briefings from Atlanta.

“He took a step back because he allowed his experts to run the show,” Markel said of Obama. “He didn’t have to be in front of the podium, but you knew he was there.”

Nearly 12,500 deaths due to the H1N1 flu were reported in the U.S. between April 2009 and April 2010, when the World Health Organization declared an end to the pandemic.

Obama spent nearly $1 billion and sent U.S. military personnel to West Africa to help with the response to an outbreak of Ebola in 2014.

Still feeling his way through his first year in office, Bush became a wartime president the instant hijackers recruited by the al-Qaida militant network flew commercial airliners with passengers into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a Pennsylvania field on Sept. 11, 2001.

Days later, Bush stood atop the rubble and memorably spoke for the nation.

“I can hear you!” Bush blared through the bullhorn as emergency responders cheered. “The rest of the world hears you! And the people — and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.”

Weeks after that appearance, Bush authorized military airstrikes against Taliban military installations and al-Qaida training camps in Afghanistan. U.S. military engagement in Afghanistan continues to this day.

___

Republished with permission of The Associated Press.