Donald Trump crushed Marco Rubio’s White House aspirations in 2016, besting “Little Marco” in a vicious contest notable for crude insults and arguments over who was more dependent on makeup and tanning beds.

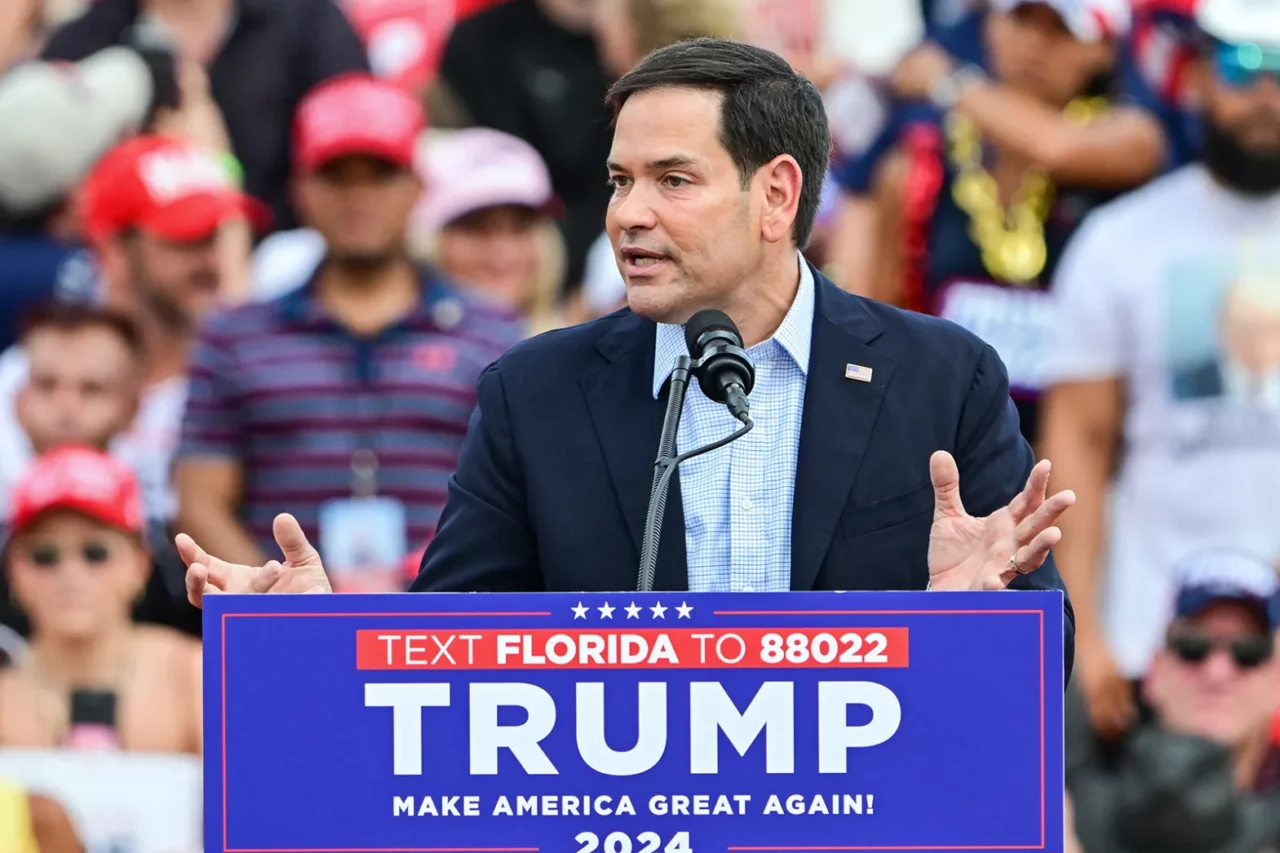

Eight years later, the 53-year-old senator from Florida is on the short list to be Trump’s vice president, along with North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum and Ohio Senator JD Vance. At a Miami campaign rally this week, Trump teased the idea of selecting Rubio as his running mate, telling the crowd that the lawmaker may not be a senator for much longer.

Joining forces would ease the path for Rubio to make his own presidential run in 2028, and may give Trump access to one-time Rubio donors who tend to favor Republicans but aren’t part of the MAGA movement. But perhaps most importantly, adding the son of Cuban immigrants to his ticket could help the former president shore up his standing with one of the fastest-growing demographic groups in the U.S. Latinos.

Creating inroads with Hispanics and Latinos has never been more critical — nationwide, they accounted for half of the increase in eligible voters since the 2020 election, some 4 million people — and many are in swing states. Pennsylvania, which Trump lost in 2020 by fewer than 82,000 votes, saw its total Hispanic population grow 10% from 2020 to 2023, or by 104,000 people, according to census data. Nevada, another key state where Trump came up short, has seen a similar surge.

“Marco can sit with Hispanic voters and talk about what they or their parents went through to get here,” said Rebeca Sosa, a veteran politician in Miami who Rubio has called his “godmother” for the guidance she provided over his career. “He can convince Hispanic voters that the Republican party is the party that doesn’t accept any communists.”

Rubio has made his Cuban heritage and opposition to communism central to his conservative political identity. In remarks to Hispanic audiences, he often tries to link the Democratic party with the types of leftist ideologies that many Cubans, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans and other Latinos fled to get to the U.S.

“No community in this country knows better than this one what they are doing,” Rubio said in Spanish at the Trump rally in Miami. “You’ve seen this film before, right? We’re not repeating that here.”

Latinos have long been a key constituency within the Democratic caucus, but those ties seem to be fraying, and Rubio could be well positioned to take advantage. While 59% of Hispanic voters cast ballots for Joe Biden in 2020, a Gallup poll conducted last year found Hispanic support for Democrats at a record low, with the margin over Republicans down by more than half from 2020 to 2023.

Trump and Biden have roughly equal support from Hispanic voters in swing states, according to a Bloomberg News/Morning Consult poll from early July. About 47% of Hispanic voters said they’d back Biden, with about 43% preferring Trump.

Of course, having a Hispanic candidate on the ticket wouldn’t guarantee support from Hispanic voters. Those concerned about treatment of migrants might be turned off by elements of the Republican National Committee’s 2024 platform, which calls for sealing the border and stopping the “migrant invasion” and carrying out the “largest deportation operation” in U.S. history.

Trump has accused immigrants coming to the U..S of “poisoning the blood of our country.”

“His messaging and policy don’t resonate inherently with Hispanic voters,” said Fernand Amandi, a Democratic pollster and lecturer at the University of Miami. Rubio’s Cuban heritage and anti-communism rhetoric has pull in Florida, but may not be as well received by Mexican-Americans and other groups in the rest of the country, he said.

“Rubio’s constantly condemning and trying to cut funding for education and health care, which are things Hispanic people in the U.S. value,” he said.

With the Republican National Convention set for next week, Trump is likely to announce his running mate in coming days. His campaign says there’s been no decision made. “The top criteria in selecting a vice president is a strong leader who could make a great president,” Brian Hughes, a senior adviser, said in an email.

Rubio’s press office declined to comment.

“Whether I’m in the Senate, or I get a chance to serve in the executive branch, I want to be a part of these issues we’re facing at this moment in our nation’s history because they’re that important,” Rubio said in an interview with CNN after the presidential debate in June. “But that’s his decision to make.”

In Florida, once considered a swing state evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats, the emergence of conservative Latino movements has helped the GOP get the upper hand. And Rubio is popular, cruising to re-election in 2022. His allies paint him as a stable, time-tested politician and gifted bilingual public speaker.

But just as significant might be his track record at raising money from GOP donors who have never given to Trump.

Ken Griffin, the founder of Citadel, gave $5.1 million to Rubio’s allied super PAC to support his unsuccessful bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 2016. Larry Ellison, co-founder of Oracle Corp., and hedge fund manager Paul Singer each donated $5 million. Norman Braman, the former owner of the Philadelphia Eagles, contributed $7 million, more than any other donor.

Griffin has said he is waiting for Trump to choose his running mate before deciding whether to support his re-election. Braman, Singer and Ellison didn’t immediately reply to requests for comment.

Among members of Trump’s VP shortlist, Rubio is closest to the traditional Republican establishment that prioritizes tax cuts and conservative social policies. He clashes with Trump and his populist tendencies on some foreign policy issues — Rubio is a well-known China hawk and has been a vocal advocate for a ban on the social media app TikTok, which Trump has flip-flopped on.

Rubio has also been a critic of Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine and a proponent of NATO, co-sponsoring a bill that prevents U.S. presidents from leaving the organization. Trump has long criticized NATO and in February said he would encourage Russia to “do whatever the hell they want” to member countries that don’t “pay their bills.”

One complication with Rubio joining the ticket is that the Constitution requires presidential and vice presidential candidates to come from different states, meaning the senator might have to change his official residency. But that aside, his presence on the ticket would highlight Florida’s increasing influence in the Republican party. Trump’s campaign manager, Susie Wiles, is a longtime operative from Florida who has crossed paths with Rubio both in DC and Tallahassee.

Rubio became the Florida House speaker in 2006 when he was 34. He shocked the Republican establishment when he won the primary for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat in 2010.

“Saying Marco was an underdog is an understatement,” said Jay Demetree, Rubio’s former finance chairman. He said Rubio’s embrace of Tea Party policies, including strident opposition to the Affordable Care Act and deficit spending, helped win the support of “hardcore Republicans, people who were really aware of the issues.”

“He’s developed a knack with donors,” Demetree added. “Frankly, I think for a lot of Republican donors in this election, having somebody like Marco as the VP would give them a sense of security.”

Some critics see Rubio’s embrace of Trump as based on pragmatism — the MAGA movement has taken over the GOP, and those who want to maintain influence in the party need to be on board. Dan Gelber, who was the Democratic leader of the Florida House of Representatives when Rubio was speaker, said he has shown flexibility before with his enthusiastic embrace of the Tea Party as it rose to prominence.

“Marco has exceptional political antennae,” Gelber said. “He realized before many that the Tea Party was not something in the hinterlands, but that it was becoming the center of the Republican party.”

Rubio and his wife Jeanette, a former Miami Dolphins cheerleader, sat in the front row for the July 9 rally at the Trump National Doral Miami, a few miles from the western suburb where he grew up. A Christian country music soundtrack played as he approached the podium.

“What a nice golf course, huh?” Rubio said. “Who owns this place anyway?”