The slogan of the Jacksonville Block by Block event, put on by the Jessie Ball Dupont Fund and the Reinvestment Fund, is a simple six word declaration.

Our homes. Our neighborhoods. Our opportunities.

On Tuesday morning, a cavalcade of Jacksonville civic leaders converged at the Jessie Ball Dupont Center (formerly the Haydon Burns Library) in the heart of downtown to discuss what was billed as a “detailed new analysis of Jacksonville’s housing markets designed to help inform decisions about Jacksonville’s future.”

To set this up, there literally was a block by block approach, hence the name. A canvassing of neighborhoods, looking at houses, apartment houses, and condos, ascertaining the status of a given property. A granular analysis, to be sure.

Sherry Magill, the Dupont Fund president, led off by discussing a major issue in Jacksonville: the lack of affordable, safe, and decent housing, a problem which stems, in part, from the foreclosure crisis of the last decade, but which also has other roots also.

Ira Goldstein of the Reinvestment Fund spoke next, discussing a major public policy challenge: socially and environmentally responsible development, that builds wealth and opportunity for lower and moderate income individuals and neighborhoods.

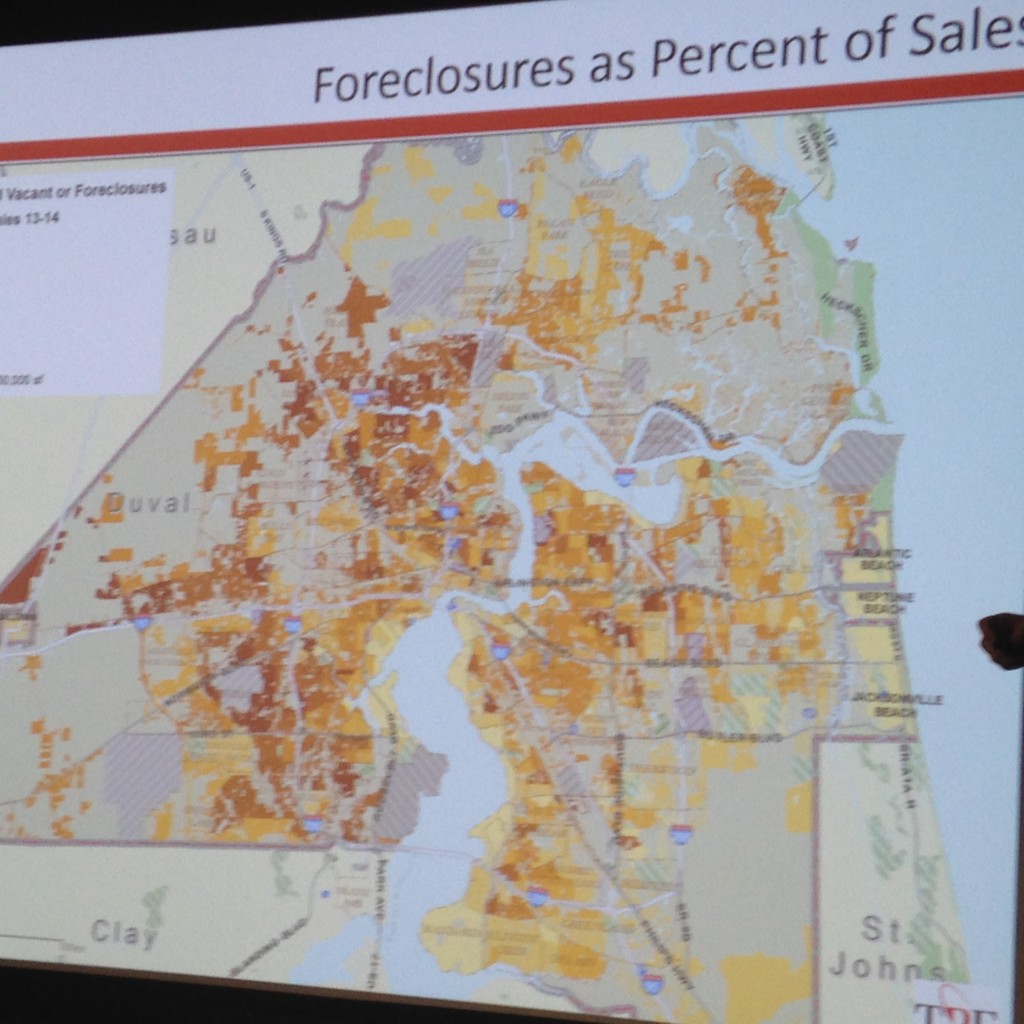

To that end, the group did a market value analysis at the census block level, accounting for variations within neighborhoods and looking for opportunities to identify issues going forward.

Neighborhoods, said Goldstein, are “not some homogenous thing” and a block group analysis depicts the “mosaic.”

Such detailed analysis is an advantage for policy types, allowing them to maximize the impact of scarce public subsidies and “build from strength,” leveraging assets ranging from roads and rivers to stable community institutions to either gentrify neighborhoods or reverse what may seem to some to be inevitable declines.

Jacksonville has over a decade of property sales data, which facilitates this analysis… an analysis that reveals what inevitably will be the focus of policy decisions going forward.

One fun fact: from 2000 to 2013, Jacksonville’s population went up almost 14 percent; available housing stock, however, increased by over 19 percent, the bulk of it built during the housing boom that preceded the foreclosure crisis.

Another fact worth mentioning: Jacksonville’s Hispanic population has, comparatively speaking, exploded over the same 2000 to 2013 time span, increasing by over 130 percent to become over 8 percent of the population.

A third fact that merits focus: as in most areas, real household and family income decreased in the same time span by roughly 10 percent.

Jacksonville, characterized by sprawl, has “nodes of strength” in housing markets throughout the city. Predictably, however, the weaker markets predominate in parts of the Urban Core, the Northside, Northwest and Midwest Jacksonville, and the Westside.

To this end, Goldstein advocates “interventions” that range from code enforcement and streetscape enhancement to foreclosure prevention, buffer tools that allow struggling neighborhoods to “draw strength” from strong proximate markets.

And foreclosures are a particular issue: over 82 percent of sales in 2013 and 2014 were either foreclosed or bank-owned properties.

Investor ownership of homes, meanwhile, predominates most in the weaker markets mentioned above, creating what Goldstein calls “potential concerns” that include “wealth stripping,” a loss of “local stakeholders,” and a “loss of local control” that begets code enforcement issues that are harder to resolve with absentee ownership.

Another topic of local interest: developing “attraction strategies” to ensure that those who work downtown live downtown or in surrounding neighborhoods.

The city, of course, has worked, both on the City Council level when Denise Lee headed the Blight Committee, and on the executive branch level, in mitigating the issues that cause neighborhood decline.

Its efforts to prevent what Councilman Bill Gulliford calls “zombie foreclosures” were described by Goldstein as a unique approach that “make the cost of doing nothing high” for derelict bank ownership.

For two members of the Lenny Curry administration, much of what Goldstein discussed was familiar.

Chief of Staff Kerri Stewart noted that “many cities are [like Jacksonville] moving toward a data-driven approach” to “inform public policy decisions” related to managing neighborhood stability.

Describing Tuesday’s program as the “tip of the iceberg,” Stewart noted that Jacksonville’s data will facilitate its moves in this area.

The big surprise for Stewart? Investor activity.

With that in mind, a next move might be to convene groups of investors, finding a way to maximize city government investment “to make private investment go further.”

For Lee, meanwhile, who is now Director of Blight in Jacksonville under Curry, what Goldstein said jibed with her experience in city government, especially when she led the City Council’s Blight Committee.

“So much of this related to what we talked about in Blight,” Lee said of the committee meetings that included input from various city departments and community stakeholders on issues ranging from dealing with vacant, blighted structures to the crime and threats to public order said structures often serve as staging grounds for.

For Lee, the goal has been to “put something in place that is long lasting,” and addressing “abandoned houses” is important to accomplishing the larger goal of breathing life into neighborhoods that seemingly were left for dead.

“Jacksonville has already started dealing with Blight,” Lee said as she settled into a breakout meeting with a couple of dozen other policy people.

The subject of that meeting? Using a market analysis to address vacancies and blight.

Our homes. Our neighborhoods.

Our opportunities.