Ben Carson is the only 2016 candidate for president who has never led a state or company or run for political office. No matter, he says. Surely someone who can perform life-or-death surgeries can run the country.

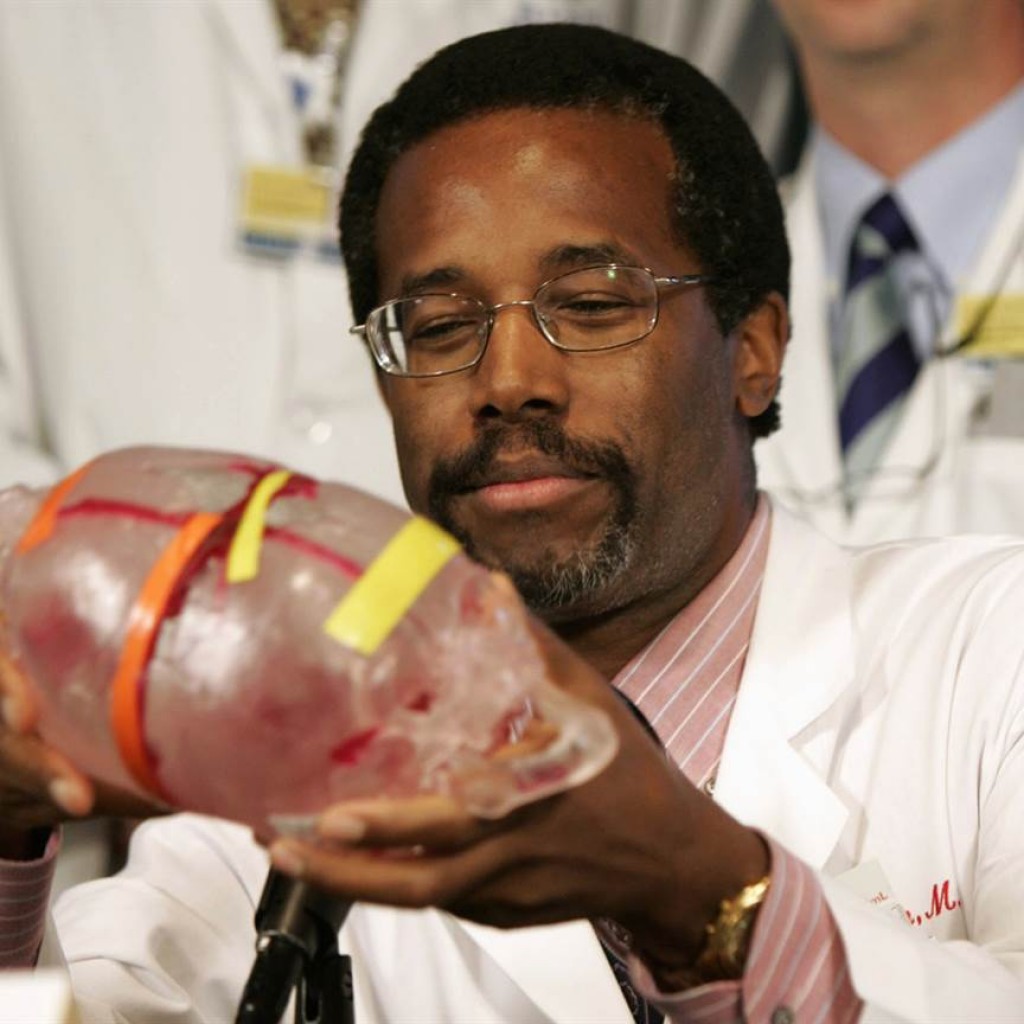

Carson challenged the medical status quo as a storied neurosurgeon — cutting out half of a child’s brain to end her seizures, separating twins joined at the head — in a three-decade career at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

“I believe in getting the best out of everybody,” Carson told The Associated Press. “In my operating room, everybody was free to speak.” He said, “I want that person who is cleaning the floor, if they see something, to say something.”

But the White House is a long way from the operating room, where the doctor with the technical skill unquestionably is the one in charge, not the best deal-maker or diplomat seeking consensus. Carson’s lack of executive experience produces deep skepticism from critics in both parties.

Yet he’s among the leaders in the Republican presidential campaign. In a new Associated Press-GfK poll, Carson has the highest positive and lowest negative rating of any Republican sized up by registered GOP voters, with 65 percent giving him a favorable rating and just 13 percent rating him unfavorably. Moreover, 62 percent of such voters think he could win the presidency if he is nominated, second only to the 71 percent who think of Donald Trump as an electable candidate.

Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who ran the Clinton administration’s “reinventing government” program, says she, like many others, is in awe of neurosurgeons and other doctors who heal people.

“We love them but, hello, that doesn’t even remotely resemble what the job of president is,” she said. Conversely, “I would not want my neurosurgeon experienced in the art of negotiation.”

At least one similarity between the professions: crises at any hour.

“He was never one of those surgeons that throws things or yells and screams,” said Dr. Violette Recinos, who was trained by Carson and now directs pediatric neurosurgery at the Cleveland Clinic. As a resident at Hopkins, she often had to wake the surgeon late at night when a patient needed immediate care. “No matter what time I called him, he was never angry, he was never grouchy,” she said.

Longtime colleagues don’t know what to make of Carson’s political persona, contrasting the doctor they saw as devoted to patients of all backgrounds with his divisive comments such as a statement that a Muslim shouldn’t be president. Pediatricians were dismayed when Carson questioned whether children get too many vaccines at once, even as he disputed any link with autism. And though he opposes abortion rights, Carson has defended co-authoring a 1992 study that used fetal tissue, telling CNN there’s a difference between performing abortions and using tissue someone else already stored.

“People have asked me what his politics were like,” said Dr. Henry Brem, neurosurgery chairman at Hopkins, who joined the faculty with Carson in 1984. “There was no politics in the hospital, zero. It was never discussed.”

Brem said Carson was “very willing to think outside the box. A lot of patients came to him that other surgeons were not willing to take the risk to operate on.”

Could the political rhetoric tarnish Carson’s medical legacy?

“There’s a part of me wishes he’d never entered the political fray,” Dr. Damon Tweedy, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Duke University, said in an interview about a hero of his youth.

Tweedy recently wrote in The Washington Post about how Carson was an inspiration for him and many other black medical students, with his rise from childhood poverty to become a pediatric surgical pioneer who established scholarships for kids. So Tweedy was stunned when Carson compared President Barack Obama‘s health care law to slavery.

In medicine, Carson is best known for leading a 22-hour operation in 1987 to separate German twins joined at the head — the first such attempt when both babies survived.

But Brem said Carson’s larger contribution was in reviving a radical operation that had largely been abandoned as too dangerous: He removed half the brain of a child with a rare condition inflaming the entire left hemisphere.

“There was a lot of fear in doing that,” recalled Brem, explaining that it works in children young enough for flexible remaining brain tissue to compensate.

Carson wrote in his autobiography “Gifted Hands,” that doctors in the past may have chosen inappropriate patients for the procedure or lacked the skills. Regardless, “we were at least giving this pretty little girl a chance to live,” he wrote.

It worked, and soon other desperate families were calling.

Carson said he doesn’t miss what medicine had become by the time he retired as chief of pediatric neurosurgery at Hopkins two years ago. No more simply flying in a child from, say, Guatemala for complex surgery. “Now it’s like, every penny, nickel and dime has to be counted, you go through 600 bureaucrats,” he said. “It just wasn’t exciting.”

And he dismisses criticism of his lack of political experience: “You need skill to bring in trustworthy people who understand the complete corruption of the system as it exists now,” Carson said. “You don’t have to be part of that.”

Republished with permission of the Associated Press.