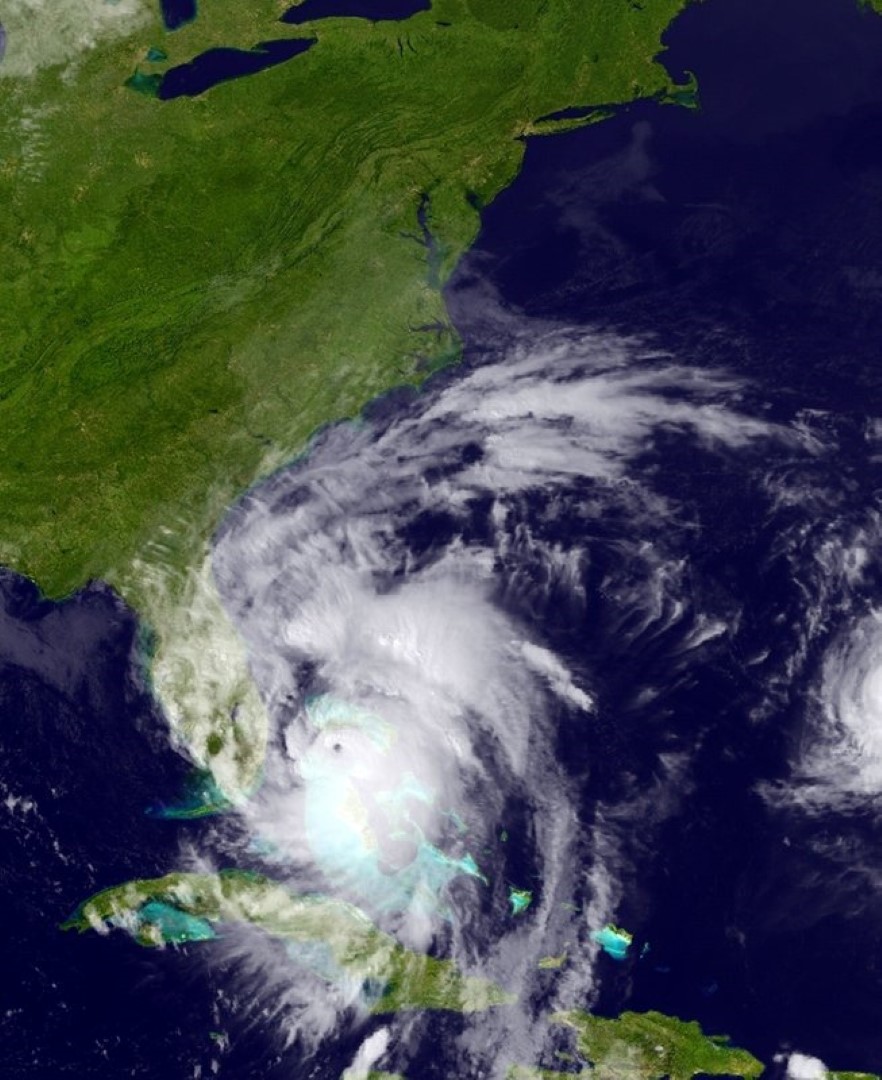

In its record-long week as a major hurricane, Matthew has threaded the needle with its track, staying over warm waters that provide fuel and avoiding land that could starve it. That’s been a bit of good news for Florida, but if does actually hit land farther up the coast — and that’s still a big question mark — that region would pay the price for Florida’s good luck.

Here are some questions and answers about Matthew:

———

Q: What does Matthew not quite hitting Florida mean for Georgia and the Carolinas?

A: It keeps the danger level higher, meteorologists say, because the close-but-not-quite-over-land track has kept Matthew’s eye relatively strong. It’s now been a week and counting as a major hurricane.

Matthew has found “one of the most ideal tracks that a hurricane can find to maintain that intensity,” said University of Miami tropical meteorology researcher Brian McNoldy.

“It probably would be weaker if it would have gone over land in Florida instead of what it’s doing,” agreed senior scientist Christopher Davis at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

Q: How tight a needle has Matthew threaded?

A: Matthew is traveling up the Atlantic’s warm Gulf Stream. A bit to the east, the water is cooler, providing weaker fuel. Just 10-to-30 miles westward is the coast, where the air is drier.

When a storm moves over land from warm water, it is like the ultimate severe diet: Eventually, it starves.

“This is a case that will probably save a lot of the coastal cities from pretty destructive wind, but the hurricane itself will maintain a lot of intensity,” McNoldy says.

Just outside the eyewall, the wind speed has dropped dramatically; by noon Friday, no place on Florida had sustained winds that were hurricane force, even though Cape Canaveral had a gust of 107 mph, says former hurricane hunter meteorologist Jeff Masters, meteorology director of Weather Underground.

That makes storm surge more of a problem than winds, at least in Florida, according to McNoldy and Masters.

———

Q: Why is Matthew hugging the coast, but not making landfall?

A: There’s no scientific reason meteorologists know of. Hurricanes are guided by atmospheric currents, not ocean flows or the cut of the coastline.

“At this point it’s just luck,” McNoldy says. “There is no real reason why this whole curve is going the shape of the coastline. It could have gone 20 miles east, 20 miles west.”

Even when Matthew passed between Haiti and Cuba, it mostly avoided land, especially mountains that could dramatically choke storms.

“It’s quite strange actually,” McNoldy says. “The atmosphere doesn’t really know about the curvature of the coastline.”

———

Q: How unusual for Matthew to stay strong so long?

A: It’s not just unusual — it’s a record, if you look at it in a certain way.

At more than a week of major hurricane strength, with sustained winds over 110 mph, Matthew beat the old record of six days for storms after Sept. 25, according to Phil Klotzbach, meteorology professor at Colorado State University. Klotzbach uses this date — after start of fall — because atmospheric and water conditions are quite different in the later part of hurricane season, making it harder for storms to stay strong.

Matthew has been moving over water several degrees warmer than average, on a track relatively free of higher, weakening winds. These conditions, especially the winds, are likely to change.

———

Q: So will the U.S. continue its “drought” of major hurricane landfalls?

A: It’s been nearly 11 years since 2005’s Hurricane Wilma, since a major hurricane made landfall in the United States, a record long time. Meteorologists had been thinking Matthew would end it, but now they say there’s a good possibility the drought will continue.

South Carolina still has a decent chance of being hit directly, but even then, Matthew could weaken just a bit and slip below major hurricane status, Masters says.

The nearly 11-year drought is an artificial construct, just random chance, Masters says. For example, Superstorm Sandy struck during that time and was devastating, but technically wasn’t a major hurricane in terms of wind speed, even if it was major for destruction. And in 2008, Hurricane Ike missed being a major hurricane at landfall by just 5 mph, so if definitions had been slightly different, no one would be talking drought, Masters says.

———

Q: Has anything good come out of Matthew’s hugging Florida?

A: Most likely yes, says Davis. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration planes fly out of western Florida and the proximity has enabled them to make many research trips.

Plus, the storm has been close enough to NOAA radar to provide scientists with good inside-the-action data, Davis says.

“In a sense, you can look at this as being a benefit in some ways to hurricane research,” Davis says. “A silver lining perhaps.”

Republished with permission of The Associated Press.