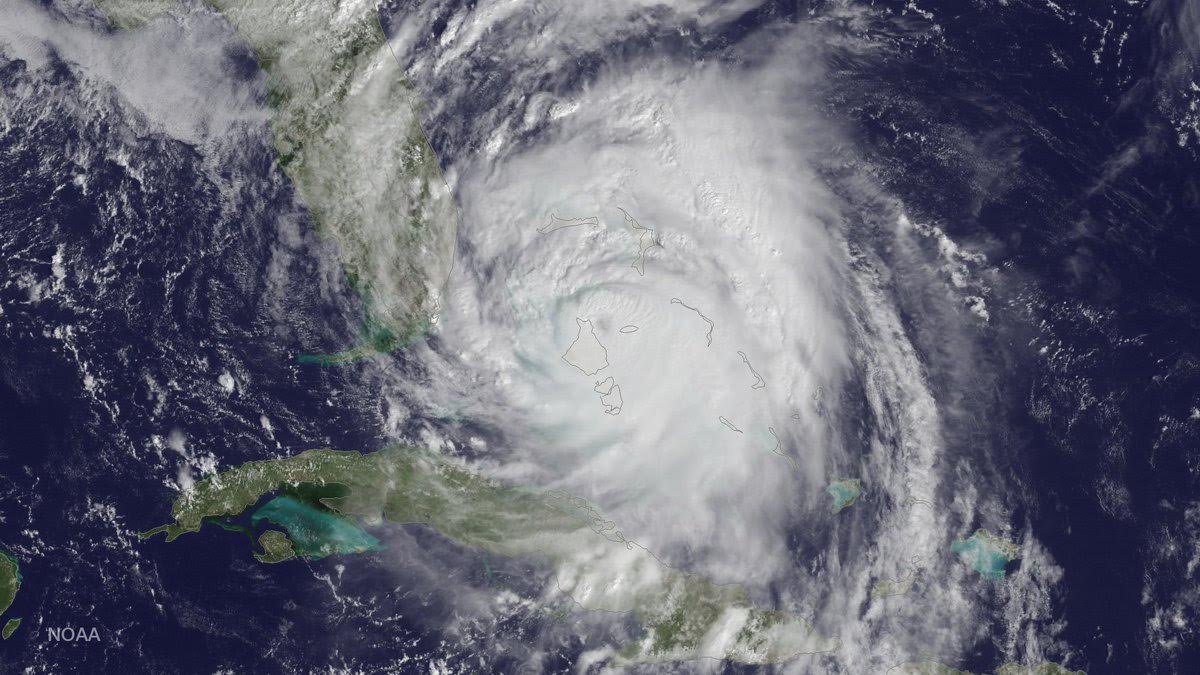

Hurricane Matthew’s close-but-not-quite-direct-hit path along the Florida and Georgia coasts skirted the difference between disaster and catastrophe, meteorologists said.

Even though Matthew eventually made landfall in South Carolina as a minimal hurricane Saturday, the path it took in the days before was a stroke of luck for the United States that meteorologists will spend years trying to understand and explain.

Here are some questions and answers about Matthew’s path that one meteorologist likened to threading a needle:

—

Q: How close a call was it for Florida and Georgia?

A: Just a 50 mile shift to the west, or even 20 or 30 miles, during the time it glided north along the coastline meant the difference between a storm that now looks like it will end up causing several billion dollars in damage and one costing $50 billion, said both Colorado State University meteorology professor Phil Klotzbach and former hurricane hunter meteorologist Jeff Masters, meteorology director at the private Weather Underground.

“People got incredibly lucky,” Klotzbach said. “It was a super close call.”

“Thankfully it was a tight enough storm that 50 miles made a pretty big difference from a wind perspective,” Klotzbach said.

Mark Bove, a meteorologist for the insurance giant Munch Re, said “if this went in as a Category 3 or 4 into Florida it would have been significantly worse.”

Still, the storm surge was bad, especially in Jacksonville, Klotzbach said.

And as lucky as the track was for the United States, it was unlucky for Haiti and the Bahamas, Klotzbach pointed out.

“It maximized the damage in the Caribbean and minimized the damage in the U.S.,” Klotzbach said.

—

Q: Why did it not go into Florida or Georgia?

A: Meteorologists are still trying to figure that out but the best answer may just be dumb luck with maybe an assist from Tropical Storm Nicole. Meteorologists said they will be studying to see if there is any good answer but so far they don’t have one.

Hurricanes are guided by atmospheric currents not anything on the ground or in the water. And this time those air steering currents — particularly high-pressure system in the western Atlantic and northeastern United States — happened to guide the storm on a path that was almost perfectly parallel to the Florida-Georgia coast, Bove said.

That, Bove said, is “pretty darn unusual.”

Masters said it was just plain luck, but Klotzbach said it is possible that the presence of Tropical Storm Nicole may have had a little bit of a hand in the path.

—

Q: So was evacuating coastal Florida and Georgia foolish?

A: Definitely not.

Even though the storm didn’t make landfall in Florida, insurance meteorologist Bove said he was certain that evacuations saved lives.

“There was plenty of storm surge all along the coast,” Bove said. “And that is deadly and unfortunately people really underestimate what storm surge can do.”

Klotzbach said people in Florida who evacuated should consider evacuation like seat belts in a car. It didn’t save you this time, but you should be glad it wasn’t needed.

—

Q: Will Matthew go down in the history books?

A: Oh yes. Data is still coming in, but it set all sorts of records so far.

Most notably Matthew goes down as one of the most potent and long-living major hurricanes — not at landfall but just spinning in the Atlantic over its lifetime.

One key meteorological measurement of a storm — Accumulated Cyclone Energy or ACE — looks at total energy based on how long a storm lasts and its wind strength over a lifetime. It’s based on measurements every six hours. In the post-1966 era of monitoring, Matthew ranks eighth among Atlantic hurricanes in ACE and likely will end up around sixth before it is completely gone, Klotzbach calculated.

And Matthew was a major hurricane — with winds of at least 110 mph — for 7.25 days, ending Friday. That makes it tied for fifth longest time as a major hurricane of the satellite era and the longest ever for a late season storm, Klotzbach said.

It also had the seventh lowest barometric pressure for storms making landfall in South Carolina. The lower the barometric pressure, the stronger the storm.

Masters said Charleston measured the most moisture ever in its air when Matthew came by. And Fort Pulaski, Georgia, and Mayport, Florida, measured the highest storm tide amounts on record with Matthew, Masters said. Charleston and Fernandina Beach, Florida, came close to records.

Republished with permission of The Associated Press.