On July 16, 1949, seventeen-year-old Norma Padgett claimed that her husband Willie was assaulted and she was raped by four black males near Groveland, Florida. Groveland is located in Lake County in central Florida.

In July 1986, I co-authored the first scholarly article on the Groveland case in the Florida Historical Quarterly, along with historians David Colburn and Steven Lawson. It wasn’t until 2013, when Gilbert King‘s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Devil in the Grove, focused national attention on Groveland.

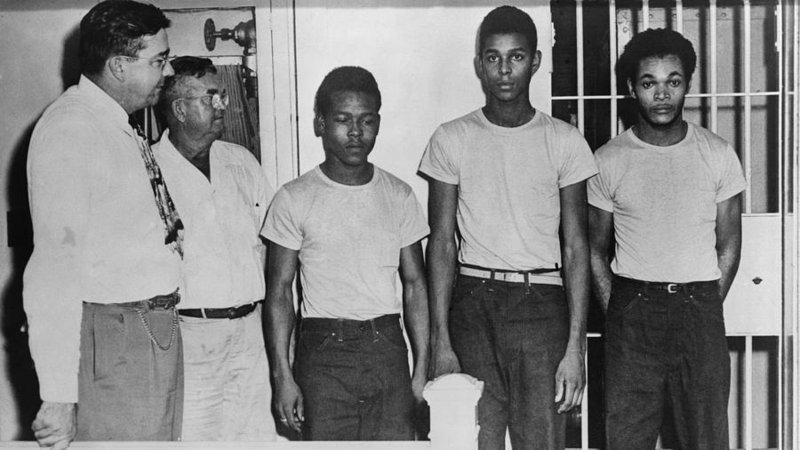

The Padgett’s told Lake County Sheriff Willis McCall that they had left a dance and their car stalled. The four blacks — Walter Irvin, Sam Shepherd, Charles Greenlee and Ernest Thomas — supposedly offered to help, but then assaulted Willie Padgett and kidnapped and raped his wife, Norma.

Sheriff McCall boasted that he was educated at the “University of Hard Knocks.” After winning office in 1944, McCall made a name for himself by attacking labor unions and civil rights groups. He accused communists of stirring up trouble among Lake County’s black citizens.

Within hours of the alleged rape, Greenlee, Shepherd and Irvin were arrested and beaten in order to extract confessions. Thomas fled the area but was killed “in a hail of gunfire” by a 1,000 man posse in Taylor County.

The fate of the three survivors seemed apparent. The day after the alleged rape, a 200 car caravan of 500-600 men descended on Groveland and demanded that Sheriff McCall turn over the three blacks to the mob. McCall lied and said the three had been transferred to Raiford State Prison. In reality, the three were hidden away in the county jail in Tavares.

Local newspapers called for revenge. The editor of the Mount Dora Topic demanded that the honor of the rape victim “be avenged in a court of law …” Another paper wrote: “We’ll wait and see what the law does, and if the law doesn’t do right, we’ll do it.” The Orlando Morning Sentinel, the largest newspaper in central Florida, ran a front-page cartoon depicting four electric chairs with the headline, “The Supreme Penalty” and the caption “No Compromise.”

The Groveland case quickly drew parallels to the Scottsboro Boys. In 1931, nine black men were accused of raping two white women aboard a train passing through Scottsboro, Alabama. In a hysterical and circuslike atmosphere, all of the defendants were quickly convicted, and eight were given death sentences.

The Scottsboro case attracted both national and international attention. The Communist Party and the NAACP intervened and won several significant victories before the U. S. Supreme Court. In May 1950, some 20 years after the original arrests, the last of the Scottsboro boys walked out of jail.

In Groveland, there were doubts that Norma Padgett had been raped. Only 17, she had fled to her parents after several beatings by her husband, Willie.

On the morning after the rape, Norma was seen outside a restaurant near Groveland. The restaurant owner’s son drove her into town and said she did not seem upset and never mentioned being raped.

It was not until Norma encountered her husband and a deputy sheriff that she spoke of being raped. Defense attorneys speculated that the Padgett’s concocted the story to protect her husband who had beat Norma after she refused him his “matrimonial rights.”

After a show trial where no evidence was presented that Mrs. Padgett had been raped, the jury deliberated for 90 minutes before returning a guilty verdict and death sentence for Irvin and Shepherd. Greenlee, only 16, was given a life sentence.

In April 1950, the St. Petersburg Times published an investigative report concluding that it was physically impossible for Greenlee to have been at the crime scene. Witnesses testified that Greenlee was 19 miles away at the time the crime allegedly occurred. They also concluded that much if the evidence to convict the defendants was manufactured by the prosecution.

The U. S. Supreme Court overturned the convictions in 1950. Justice Jackson said the pretrial publicity was “one of the best examples of one of the worst menaces to American justice.” The circus atmosphere prevented a fair trial, and there was evidence that the confessions were coerced.

In 1951, Sheriff McCall went to Raiford Prison to transport Irvin and Shepherd back to Tavares for a new trial. McCall claimed he had a flat tire and was attacked by the prisoners in the process. Shepherd died, but Irvin, despite being shot three times at point-blank range, survived his injuries. Irvin claimed that he and Shepherd did not attack McCall, but were killed in cold blood by the Sheriff.

In a 1952 retrial of Irvin, he was once again convicted and given a death sentence. Governor Leroy Collins, in 1955, commuted the sentence to life in prison. Irvin was paroled in 1968 and died the following year. Greenlee was released in 1960 and died in 2012.

Four innocent black men suffered grievously for a crime they never committed. Thomas was killed by a vigilante posse, and Shepherd was killed by Sheriff McCall. Greenlee also spent a decade in prison, and Irvin also spent two decades in prison for a crime they did not commit.

On April 27, the Florida Senate passed a resolution apologizing to the families of the four black men who the Senate said were “victims of racial hatred.” I am sure they are comforted in their graves.

___

Darryl Paulson is Emeritus Professor of Government at USF St. Petersburg specializing in Florida and southern politics.