One of the biggest takeaways from watching several hours of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional testimony was the sheer lack of understanding among many lawmakers about how Facebook actually works.

One of the biggest takeaways from watching several hours of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional testimony was the sheer lack of understanding among many lawmakers about how Facebook actually works.

The latest controversies surrounding this global social network, from Cambridge Analytica to Russian election meddling, have been twisted and misconstrued by pundits and politicians — similar to an elementary school game of telephone. Few understand what actually happened and even fewer know what needs to be done to solve the social network’s challenges.

All of this was best revealed when Sen. Orrin Hatch purposely questioned how Facebook could make money without a paid subscription model. Zuckerberg paused and then responded with a smile, “Senator, we run ads.”

Facebook does have user data issues, which show up through apps and ads. The Cambridge Analytica controversy, which involved a third-party app developer selling user data to an advertising agency, was made possible by a 2014 vulnerability (now solved) in how Facebook shares data with app developers. Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. elections was an advertising issue, with masked Russian agents paying to place divisive, emotionally charged social media posts in front of various groups of the American electorate in hopes of creating confusion and consternation.

To clarify what’s actually at stake, answering several questions that keep popping up, but that few seem to understand, will be helpful.

Does Facebook sell user data?

No. In 2017, Facebook made 98.2 percent of its revenue from advertising. The remaining 1.8 percent was a result of people buying virtual goods from games they play on Facebook (think Farmville), with the social network taking a small cut from each transaction. These payments, similar to how Apple takes a cut on every app purchased through iTunes, are shrinking each year as more users move to mobile — where fewer users play Facebook games and buy virtual goods.

Rather than sell user data, Facebook leverages it to offer advertisers some of the best and most accurate targeting tools available anywhere today. If you want to place your ad in front of a 36-year-old woman in Nashville, for instance, you could use Google, but their targeting tools are primarily built on guessing games (supposing, for example, that people who visit 14 particular websites are likely 35 to 44 years old). With Facebook, users voluntarily provide this data, making it unprecedented for its accuracy and potential to place highly relevant ads in front of the right groups of people.

That’s what this all comes down to: Facebook wants its users to be presented with as many highly relevant ads as possible. If Facebook users consider the ads in their news feeds to be relevant, then they are more likely to click through and engage with the content and take an action, whether that means buying a product, attending an event, downloading a mobile app, or voting for a political candidate. If advertisers do not receive a sufficient return on their investment, they will abandon Facebook and shift their advertising budgets to other advertising platforms.

Our firm has conducted Facebook advertising campaigns — promoting products and issues — for more than a decade, spending millions of dollars on behalf of hundreds of clients. At no time have we had access to the personal data of individual Facebook users. Even when Facebook is provided with a list of people to target with ads (e.g., a company’s existing customers or subscribers), Facebook encrypts that data and removes all personally identifiable characteristics.

For example, no one could specifically target “John Smith in Springfield, Missouri” by name with a particular ad. You could target groups of hundreds, thousands, or millions of users with advertising content that you hope is relevant enough to encourage them to interact with the content and take additional action.

In the Russian election scandal, foreign agents attempted to cloud and cause fallout on the American political landscape by creating Facebook Pages about various controversial issues, running ads encouraging people to follow those pages and then publishing divisive content into their news feeds. They used the ad targeting tools mentioned earlier for nefarious purposes, attempting to manipulate Americans.

Did this Russian campaign impact the 2016 U.S. election and its campaigns? That all depends on whether you believe people have control over their own viewpoints or if they are molded entirely by the messages they see on a daily basis. We all surely hope the outcome was not shaped by this dark work.

What actually happened with Cambridge Analytica?

In 2014, Cambridge University researcher Aleksandr Kogan created a Facebook quiz app called “This Is Your Digital Life.” In order to use the app, 270,000 Facebook users gave Kogan permission to access their public profile, page likes, friend lists and birthday. By gaining access to these friend lists, Kogan also received access to the friends’ public profiles.

When media and politicians refer to 87 million users, they are talking about those friends’ public profiles. It’s important to note, however, that the information Kogan received about users’ friends from their public profiles is what anyone could have accessed with a simple search for Facebook users. Kogan did not receive access to private data, such as credit card numbers, Social Security numbers, purchase activities and travel history. All accessible information was publicly available. There was no breach or hack of Facebook’s system — Facebook merely made it easier for Kogan to have access.

Once Kogan had this user data, he sold it to Cambridge Analytica and a couple of other research firms, which violated Facebook’s terms of service. When Facebook found out, they told them to delete the data. Cambridge Analytica reported to Facebook that it had deleted the data, but this was untrue. Facebook now acknowledges it should have conducted a more thorough audit to confirm the deletion and should have informed users about the violation at the time it occurred.

Shortly after, Facebook restricted what information app developers could access via users’ friends lists. Facebook’s app developers have not been able to access the data in question for the last four years.

During the Senate committee hearing, several senators commented about the complexity of Facebook’s Terms of Service, implying that it was the only document users had to accept before the social network would share user data with app developers.

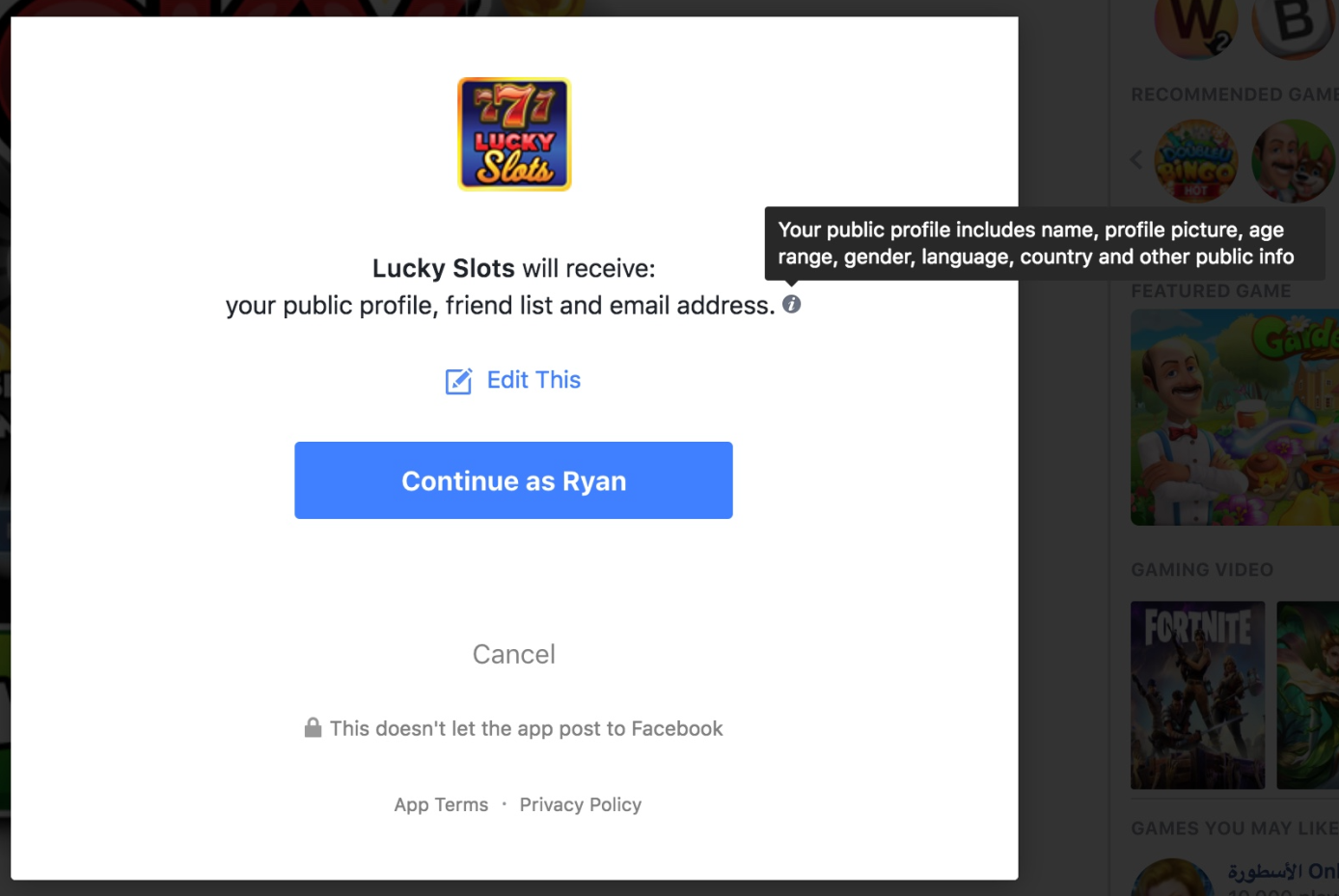

But the truth is Facebook shows users a permissions page and requires their approval before they can use an app and the requested data is then shared with app developers. Here’s an example of the permissions page:

Could Facebook launch a paid subscription, and how much would it cost?

Facebook could launch a paid membership with no advertisements and no capture of user data, but it would be reluctant to take that path. Here’s why:

Facebook earned $82.44 in advertising revenue per average American user in 2017, up 35 percent from $60.90 in 2016.

If a paid subscription merely reimbursed Facebook for the amount it would lose in advertising revenue, then Facebook would have to charge users $6.87 per month. But with advertising revenue per user expected to continue climbing in the years ahead, that subscription fee would have to either increase each year or be set at a much higher price point.

Why do advertisers flock to Facebook more than other social networks, like Twitter? Aside from Facebook’s superior ad targeting capabilities, advertisers have the opportunity to reach many more users on Facebook. If you start chipping away at the number of people you can reach with ads on Facebook, then advertisers may be less likely to invest in the social network, which then dilutes the overall advertising platform’s value.

And who would be most likely to switch to a paid subscription? If it were priced at $7.99 or more, it’s likely that the population of paid subscribers would be wealthier and more educated than the average user. Those wealthier, more educated users happen to be some of Facebook’s most desired users from an advertising perspective. Facebook does not want to lose advertisers’ top targets — or any segment of its massive global audience.

So how do you police Facebook?

Facebook has 2.1 billion users worldwide. That’s 28 percent of the world’s population accessing Facebook at least once a month, and 18 percent accessing it daily.

Even more striking is that 2 in 3 Americans access Facebook each month.

How do you police the communication of 1 in 4 people around the globe, including 2 in 3 Americans? No organization in human history has been tasked with such a monumental challenge. So, to what extent should Facebook police the world’s communication?

Facebook got into hot water in 2017 for censoring conservative news in its Trending Topics section. In response, Facebook replaced most of the human involvement with an automated computerized review, but that has created a slew of new problems. So what’s the right answer?

Facebook has employed hundreds of experts in this arena in hopes that they may continue to research how to best develop an appropriate strong solution.

It is doubtful that Congress will be able to solve this and other challenges facing Facebook’s future. But it is apparent that without careful consideration, members of Congress may create more problems through politically motivated rash and reckless regulations.

That would not serve the interests of anyone except politicians seeking to claim credit and advantage from it in the never-ending quest for sound bites and talking points to use in the upcoming 2018 elections.

___

Ryan Cohn is a partner, executive vice president of Sachs Media Group.