For a generation, mid-April has delivered some of American life’s most cataclysmic moments — a week when young men have shot up schools, terrorists have blown up fellow humans, members of a religious sect have burned to death in their compound and environmental calamity has sullied the ocean.

Now, as those traumatic, unwelcome anniversaries of the past 27 years roll by in the space of a single spring week, overlay one of the most disruptive moments in all of American history, even as it is still unfolding: the coronavirus, and the efforts to contain it.

What is it about this one particular week in April, anyway? And what does it mean — for survivors, and for all Americans — to move through this barrage of violent memories knowing that life as we know it, at least for now, has gone away?

“In April, things tend to happen. I don’t think it’s an accident that a lot of events take place in April. That’s the month that people have been waiting for,” says John Baick, a historian at Western New England University in Massachusetts.

He has been noticing the propensity for upheaval in April since he was in college. “There is,” Baick says, “something about the spring that goes against rationality.”

It was easy to believe it on Monday, 25 years after the Oklahoma City bombing and the day after the 21st anniversary of the Columbine High School shootings in Colorado — and, not entirely incidentally, a day after Canada’s deadliest mass shooting.

For the record, the other American cataclysms of mid-April in the late 20th and early 21st centuries alone:

— Waco, where the U.S. government raided a compound of the Branch Davidians sect on April 19, 1993, killing 76 in the raid and the fire that followed.

— Virginia Tech, where student Seung-hui Cho shot and killed 32 people and wounded 17 others on April 16, 2007.

— The explosion of BP’s Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig on April 20, 2010, which killed 11 crewmen and triggered the largest marine oil spill in history.

— The Boston Marathon bombing, when brothers Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev detonated two bombs that killed three people and wounded several hundred others on April 15, 2013, setting off a four-day manhunt that ended with two officers dead.

As these anniversaries unfolded over the past week — each with its own enduring trauma, its own survivors, its own communities affected — the stress of both the coronavirus and anti-coronavirus measures have changed how the events are remembered.

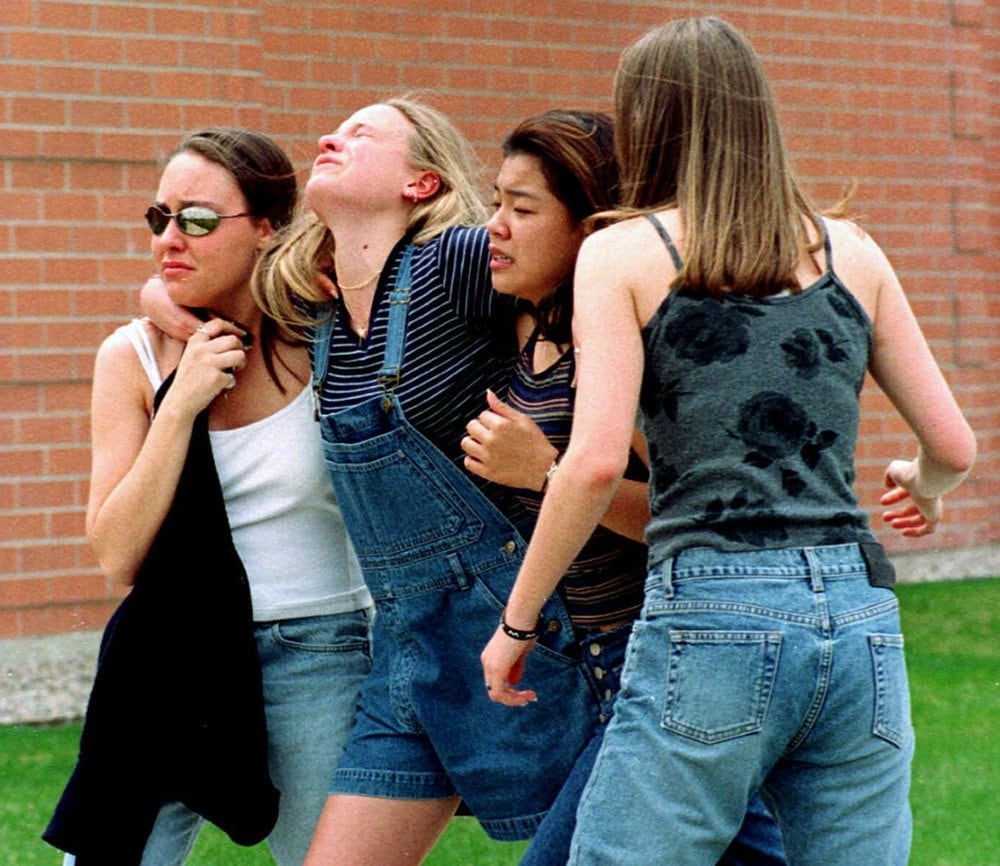

At Columbine, where two heavily armed students, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, killed 12 classmates and a teacher on April 20, 1999, the annual private gathering of survivors and families at the school was replaced by a streamed online ceremony because of COVID-19 restrictions.

Then-principal Frank DeAngelis, who organizes the yearly ceremony, said the lack of human contact made this year’s anniversary tough — but also provided new opportunities.

“We did the best we could, and just could not think of not doing it,” DeAngelis said. “One of the many positive things to come out of it this year was more people were able to see that moment. … I think it provided hope.”

Same story in Oklahoma City, where the Alfred P. Murrah Federal building was destroyed by domestic terrorist’s Timothy McVeigh’s bomb on April 19, 1995, killing 168 people. The annual commemoration on the building’s grounds was canceled and a one-hour video produced in its place.

Ryan Whicher, whose father, U.S. Secret Service Agent Alan Whicher, was killed in the bombing, said it was “extremely difficult” not be able to attend in person.

“But it’s all for the right reasons,” Whicher said. “Everyone is making sacrifices. I don’t think it’s fair for us in this coronavirus (environment) to feel we should be treated any differently.”

Beyond the core groups marking these sad moments, though, is the effect on the general public. Are the anniversaries now less noticeable because of the fatigue of American life shutting down, with social distancing in full force? Or would such milestones make things more intense for people already struggling with a changed world?

“Does something like COVID take up so much bandwidth that news coverage of past events matter less this year? I can see how plausibly you’d go both ways,” says Bethany Lacina, a political scientist at the University of Rochester who studies the interplay of politics and American popular culture.

She also researches human conflict and notes that winter’s harshness often dissuades mayhem and crime, which then tend to emerge with the thaw. “Unpleasant weather depresses political violence of all sorts,” Lacina says.

The notion of waiting until spring to take action, to wage war, to attack or just to speak out forcefully certainly has some precedent in American history.

Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth on the night of April 14, 1865, and died the next morning. The first major protest against the Vietnam War was on April 17, 1965, in Washington, drawing about 20,000 demonstrators. The upheaval after Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 assassination extended into mid-April.

Even more salient than those, perhaps, is this date: April 19, 1775, the day the “shot heard ’round the world” — the battles of Lexington and Concord — kicked off the American Revolution.

Apryl Alexander, a clinical assistant professor of psychology at the University of Denver, works with people who experience trauma more than once. She sees links between the violent events of mid-April in modern America and the current coronavirus saga.

For one, “a lot of these tragedies were related to some sort of systems failure,” just as with the virus’ spread. What’s more, she says, the stress of what Americans are enduring today is difficult enough without overlaying old bad news.

“We’re inundated with all this information that’s not really hopeful. And now you’re going to add these memories of these prior situations on top of that? That’s going to exacerbate your stress,” says Alexander, a Virginia Tech graduate who was living in the community in 2007.

“This experience we’re going through with COVID is a trauma,” she says. “And I don’t think many people are reflecting on that.”

___

Republished with permission from the Associated Press.