Democratic leaders have a potent dynamic on their side as Congress preps for its first votes on the party’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill: Would any Democrat dare cast the vote that scuttles new President Joe Biden’s leadoff initiative?

Democrats’ wafer-thin 10-vote House majority leaves little room for defections in the face of solid Republican opposition, and they have none in a 50-50 Senate they control only with Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote. Internal Democratic disputes remain over issues like raising the minimum wage, how much aid to funnel to struggling state and local governments and whether to extend emergency unemployment benefits for an extra month.

Yet with the House Budget Committee planning to approve the 591-page package Monday, Democrats across the party’s spectrum show little indication they’re willing to embarrass Biden with a high-profile defeat a month into his presidency.

Such a setback would deal early blows to both Biden and new Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York. It could also wound congressional Democrats overall by risking repercussions in the 2022 elections if they fail to unite effectively against clear enemies like the pandemic and the frozen economy.

“You think very seriously before casting a deciding vote against your own party’s president’s legislative agenda,” said Ian Russell, a longtime Democratic consultant. But he cautioned that lawmakers must decide “for themselves how their vote is going to play out” at home.

The issue that’s provoked the deepest divisions is a drive, largely by progressives, to boost the federal minimum wage to $15 hourly over five years. The current $7.25 minimum took effect in 2009.

“It was the No. 1 priority for progressives,” Rep. Pramila Jayapal, the Washington Democrat who is chairwoman of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said in an interview last week. “This is something we’ve run on and something we’ve promised to the American people.”

An overall relief bill, including the minimum wage boost, is expected to clear the House, and likely the Senate as well. But the minimum wage boost’s fate is shakier in the Senate, where Joe Manchin of West Virginia, perhaps the chamber’s most conservative Democrat, has said the $15 target is too expensive.

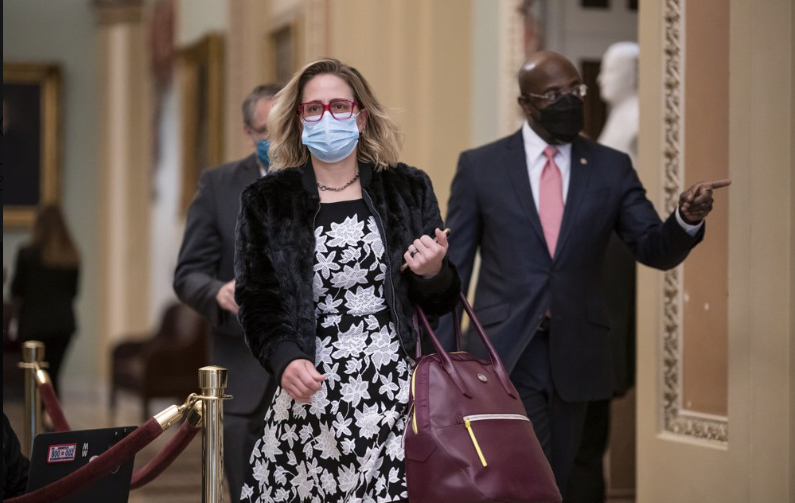

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, an Arizona Democrat, has suggested she might oppose it, too. She said Democrats shouldn’t whisk it to passage using special rules that would let them avoid a Republican filibuster, which would require an unattainable 60 votes to overcome.

Manchin’s office did not make him available for an interview. Earlier this month he told The Hill, a political publication, that $11 hourly would be “responsible and reasonable.”

Even more ominously, the Senate parliamentarian is expected to rule soon on whether the minimum wage provision must be tossed from the bill. Under expedited procedures Democrats are using, items can’t be included that aren’t principally budget-related, and it’s unclear if Democrats would have the votes to overturn such a decision.

Yet even in a Congress where virtually every Democratic vote is needed, few if any are overtly threatening to take the entire bill down unless they get their way.

Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent,his chamber’s chief minimum wage sponsor, said Democrats must “act boldly” and approve a package with the minimum wage increase. He answered indirectly when asked if he’d be willing to compromise to keep the plan in the overall bill.

“Every Democrat understands that at this moment in history, this unprecedented moment of pain and suffering for working families, it is absolutely imperative we support the president, that we do what the American people want and we pass that package,” he said in an interview.

Moderate Rep. Brad Schneider, an Illinois Democrat, also signaled a distaste for intractable demands. The pathway to success is to “push as hard as you can to get as much as you can now that you want, not compromise your principles and know that tomorrow’s another day,” said Schneider, a leader of the New Democrat Coalition, a group of nearly 100 moderate House Democrats.

Republicans say the proposal is overpriced, not targeted to people who most need help, insufficiently prods schools to reopen and is a partisan Democratic power play to ignore the GOP.

The bill would provide one-time $1,400 payments to millions of low- and middle-income people, increase child tax credits that could be paid in advance and monthly and provide extra $400 weekly federal unemployment benefits through August. It would also provide hundreds of billions of dollars for state and local governments, shuttered schools, COVID-19 vaccines and testing and struggling airlines, restaurants and other businesses.

History has rich examples of lawmakers who’ve faced pivotal decisions on whether to loyally back priorities of their parties’ presidents, with mixed results.

In 2017, three GOP defections — most famously a post-midnight thumbs-down by the now deceased Sen. John McCain of Arizona — brought down then-President Donald Trump’s trademark effort to repeal the Obama-era Affordable Care Act. McCain’s vote sparked unending enmity from Trump. Of the other two, Maine Sen. Susan Collins was reelected last year and Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski faces reelection in 2022.

In 1993, new President Bill Clinton’s $500 billion deficit-reduction plan passed the House by a single vote after freshman Rep. Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky agreed to support it. Mezvinsky, who’d previously criticized the measure as lacking sufficient spending cuts, voted “yes” after Clinton sought her backing in a phone call she took in the House cloakroom during the vote.

“I told him I knew how important it was and I wouldn’t let it go down, but I said I would only be the tie-breaking vote,” she recalled this week in an interview. She said she also told him, “If I pull you over the top, you’ll lose this seat.”

Both scenarios played out.

The package passed 218-216, saved by her decisive vote. And the lawmaker, whose last name is now Margolies following divorce, lost her reelection two years later from what was a heavily GOP district in Philadelphia’s suburbs.

She never returned to Congress. But one of her children, Marc Mezvinsky, later married Clinton’s daughter, Chelsea.

____

Republished with permission from the Associated Press.