There was an assumption among observers leading into the 2020 General Election that in counties where more Americans died from COVID-19, more voters would support Joe Biden, who promised to take stronger steps than his opponent to stifle the virus.

But the opposite ended up happening, according to a peer-reviewed study by Northwestern University, which found an inverse relationship between county coronavirus death rates and increased Democratic voter turnout.

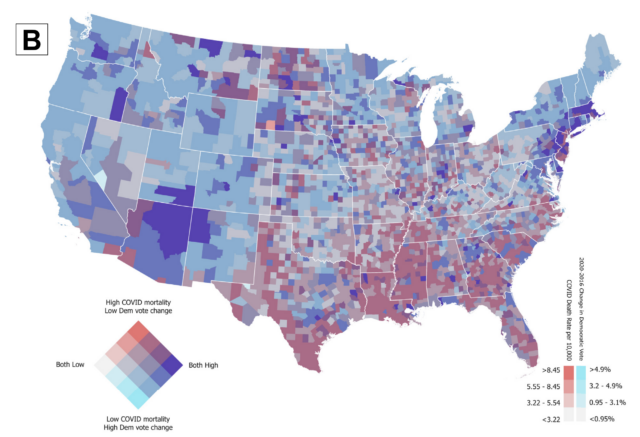

Researchers at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine examined voting and COVID-19 death data for 3,104 counties, representing more than 322 million Americans, to calculate changes in the Democratic vote from 2016 to 2020.

They separated counties into four groups, each composed of about a quarter of the United States population, based on COVID-19 deaths. On one end was a quartile consisting mostly of suburban and rural counties whose combined 80 million residents saw fewer than 3.22 deaths per 10,000 people before Nov. 3. On the other: a quartile of 80 million Americans living in counties with large, densely populated cities like Miami, New York, Detroit, Philadelphia and Chicago, where there had been at least 8.45 deaths per 10,000 residents.

After tabulating the data, weighing the study by county populations and controlling for demographic, health status, unemployment and economic factors, the researchers were shocked to find a less than 1% uptick in Democratic voter turnout in the highest-death-rate quartile compared to a 4.3% increase in counties least impacted by the virus.

“Previous experience, literature and research suggests that a crisis like this would fall upon the incumbent party to take a lot of the blame and then suffer politically or in elections, so it was reasonable to think the same would happen here, that people would see people dying and this crisis going out of control and blame the party in power, which at the time was Donald Trump and the Republicans,” said Dr. Aaron Parzuchowski, a third-year medical resident at Feinberg who led the study. “What we saw was that though turnout across the board was up, it was much less so on the Democratic side in counties hit hard by COVID. The pandemic seemed to suppress that increased turnout in the high-mortality areas. It didn’t really drive people to the polls.”

While Biden defeated Trump in 65% of the counties in the highest mortality quartile, those victories frequently came by smaller margins than what Hillary Clinton enjoyed in 2016. For example, New York City’s five combined counties had a staggering mortality rate of 28.6 deaths per 10,000 residents, but registered 2.5% fewer Democratic votes than in 2016. In Philadelphia, which experienced 12 deaths per 10,000 residents, the Democratic vote dropped by more than 1%.

The reverse took place in the lowest mortality quartile, where more than 54% of residents lived in counties Trump won last year. In one example, Waukesha County in Wisconsin, a predominantly Republican suburb of Milwaukee, had a mortality rate before the election of 3.2 COVID-19 deaths per 10,000. The Democratic vote there was 5.6% higher than it was four years before.

Across the board, counties where the death rate was highest had a 1.5% increase in Trump votes over 2016 numbers, while voting in the lowest death rate areas grew by 1.1%.

Those shifts are evidence of an ongoing realignment of U.S. political parties, said Northwestern research professor Joseph Feinglass, who worked on the study with Northwestern data librarian Kelsey Rydland, Parzuchowski and fellow internal medicine residents Dr. Andrew Peters and Dr. Cecelia Johnson-Sasso.

“You’re seeing more and more that the educated, more affluent population is moving Democratically while the less educated population, particularly most Whites, is moving more Republican. That’s reflected in the suburban areas that had a big change in the Democratic vote, whereas working-class areas that had a tradition of voting Democratic have gotten less and less so,” he said. “The other big factor was — and we know this so well from the months since the election — that people’s views of the COVID (pandemic) may not reflect their own material interests in surviving COVID. You can have a situation where people who even have a high death rate may have decided that shutdowns and the economic fallout of COVID mitigation efforts were negatively perceived, even though their risk of COVID was high.”

Overall, voter turnout in 2020 grew by 8.3% compared to 2016, as two-thirds of eligible voters cast a record 155 million ballots. However, a Census survey found that 4% of registered nonvoters cited concerns about COVID-19, which by Election Day had killed more than 230,000 Americans, as their reason for not voting.

Biden ultimately toppled Trump to capture the American presidency with 51.3% of the popular vote and 306 nods from the Electoral College. But although the incumbent President’s “anti-science” approach failed, Feinglass said, the fact it did so by such a narrow margin may have long-lasting implications.

“Apparently a bet was made, probably by the right wing of the Republican Party, that opposing government intervention against the COVID (pandemic) was going to be popular with working-class voters who feared for their economic security,” he said. “So, they made a calculated bet that by coming out … and questioning the role of government in fighting the COVID (pandemic) … that this was a way to win working-class votes. To some extent, they were successful. In the down-ballot races, it certainly helped them.”

One comment

PeterH

September 14, 2021 at 8:05 am

Another excellent analysis! Thanks!

Comments are closed.