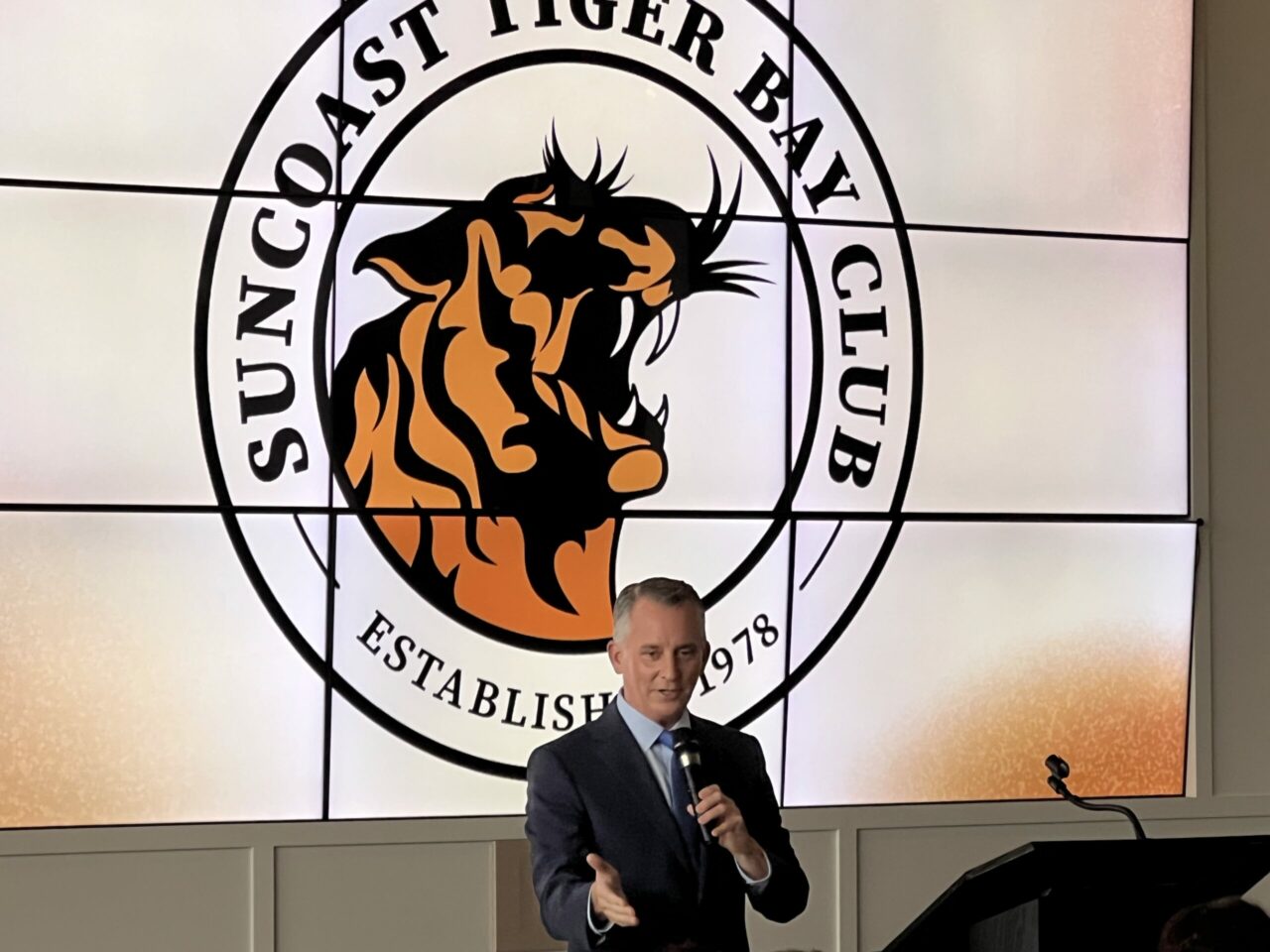

“As a Democrat, I get to believe in math,” said Democratic gubernatorial candidate David Jolly, speaking at a sold-out show at the Museum of History in St. Pete on Aug. 25. The line drew a wave of chuckles from a crowd where Jolly campaign buttons – styled with a 1960s counter-culture flair – clung to the lapels of sweaters and jackets.

Jolly’s quip was meant to underscore his political journey from Republican to Democrat, but it also invited an unintended comparison: a mathematical problem Jolly may not yet want to calculate – how his friendship with Clearwater businessman and now-indicted fraudster Leo Govoni will subtract from his campaign.

Between 2009 and 2025, Govoni — Jolly’s former legislative assistant, financial co-Chair during his 2016 Senate race and longtime friend – allegedly defrauded more than $100 million from people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs) through his nonprofit, the Center for Special Needs Trust Administration (CSNT).

Prosecutors say that for years Govoni diverted money from trust accounts into a web of private companies, personal luxuries and risky ventures. By 2024, the organization collapsed into bankruptcy, leaving thousands of disabled clients and their families in financial limbo, families that entrusted Govoni to provide a continuum of care for a vulnerable, underrepresented group.

The fallout has been devastating. Judges have already held Govoni liable for more than $120 million, ordered asset seizures, and handed down daily contempt fines as investigators untangle his businesses. Federal charges of wire fraud, money laundering and bankruptcy fraud now carry the threat of decades in prison.

Govoni has pleaded not guilty to these allegations and is currently held without bail, which is highly unusual for a non-violent crime.

Jolly has called the story “gut-wrenching” and further stated, “If he’s guilty, they should throw the book at him.” But the scandal has cast a shadow that won’t easily lighten. Jolly’s ties with Govoni run deep. In addition to their political history, Jolly’s wife, Laura Donahue Jolly, worked for Boston Holding Company – one of Govoni’s businesses – fueling speculation about whether he and Laura directly benefited from Govoni’s scheme.

It’s important to note that Jolly has not been indicted, nor is there evidence that he was aware of Govoni’s activities. Govoni has funded numerous Republican candidates (and some Democrats) through both corporate and personal donations.

Nonetheless, Jolly’s proximity to the fraudster will be a point of contention on the campaign trail. “These connections will become a large distraction eventually for the Jolly campaign,” warned the Chair of the Republican Party of Florida, Evan Power, suggesting that the issue has staying power.

According to Power, the relationship cuts to the very heart of Jolly’s candidacy: “This relationship brings up big questions on the trustworthiness of David Jolly. It goes to the core of his candidacy so there is no ability to distance from the situation.”

Barry Edwards, a longtime political consultant and Jolly confidante, echoed those doubts, saying Jolly “always held himself to a lofty standard with contributions.” When pressed, Jolly said that Govoni “collected politicians,” but did not clarify whether he counted himself in that collection.

Instead, Jolly has sought to pivot the conversation to policy, offering a campaign promise to reduce the wait time for IDD Medicaid benefits, bringing the wait time down “from 10 years to zero.”

For further context, Florida lacks adequate funding and timely services for individuals affected by IDD, with some reportedly languishing on Medicaid waiting lists for up to 10 years.

“We need a surge of resources,” Jolly said in response. “It’s a discretionary budget issue, and [those with IDD] are one of the most overlooked communities in the country.”

But some remain skeptical of Jolly’s shift. Edwards told Poliverse: “I think it’s irrelevant that he’s on that [IDD] position. I have yet to see him condemn Govoni.” (Although Jolly has said, “throw the book at him” if Govoni is guilty.)

Edwards continued, “Jolly always positioned himself against campaign funding, and yet it appears he took money [from Govoni] for his campaign.”

The criticism not only questions Jolly’s funding but also touches a core contradiction in Jolly’s political career. As a Republican Congressman in 2016, he introduced the STOP Act, a bill that would have barred lawmakers from personally soliciting campaign cash.

“That was his first fatal move,” said Edwards. Introducing the bill backfired, alienating him from GOP leadership.

Around the same time, Jolly branded himself a “never-Trumper,” further estranging him from the party. “That was his second fatal move,” Edwards added, highlighting that Jolly didn’t anticipate Trump’s reelection.

Jolly’s reinvention as a Democrat is the natural continuation (or consequence, maybe) of that trajectory, and the Govoni scandal makes it harder for him to reconcile his message with his past.

His sudden promise to slash Medicaid wait times may resonate with sympathetic voters and placate brow-furrowing skeptics – and would, if advanced, positively impact the lives of those with IDD.

But whether that is enough to explain away his association with Govoni and convince the public that he was unaware of the actions that led to Govoni’s indictment remains uncertain.

___

Aaron Styza reports; content provided in partnership with Poliverse.press.

One comment

Ron Ogden

August 31, 2025 at 9:32 am

All of which is interesting but the bottom line for Jolly is that he will never convince more than a few middle Republicans to vote for him, and there are not enough Democrats to elect him. NPAs, you say? Nope. Just look at Charlie Crist’s explosive flameout to see what happens to people who can’t decide whether they are this or that or somewhere in between