In the city named for Andrew Jackson, discussions involving race and the history of the South have often been fraught with awkward associations to the past.

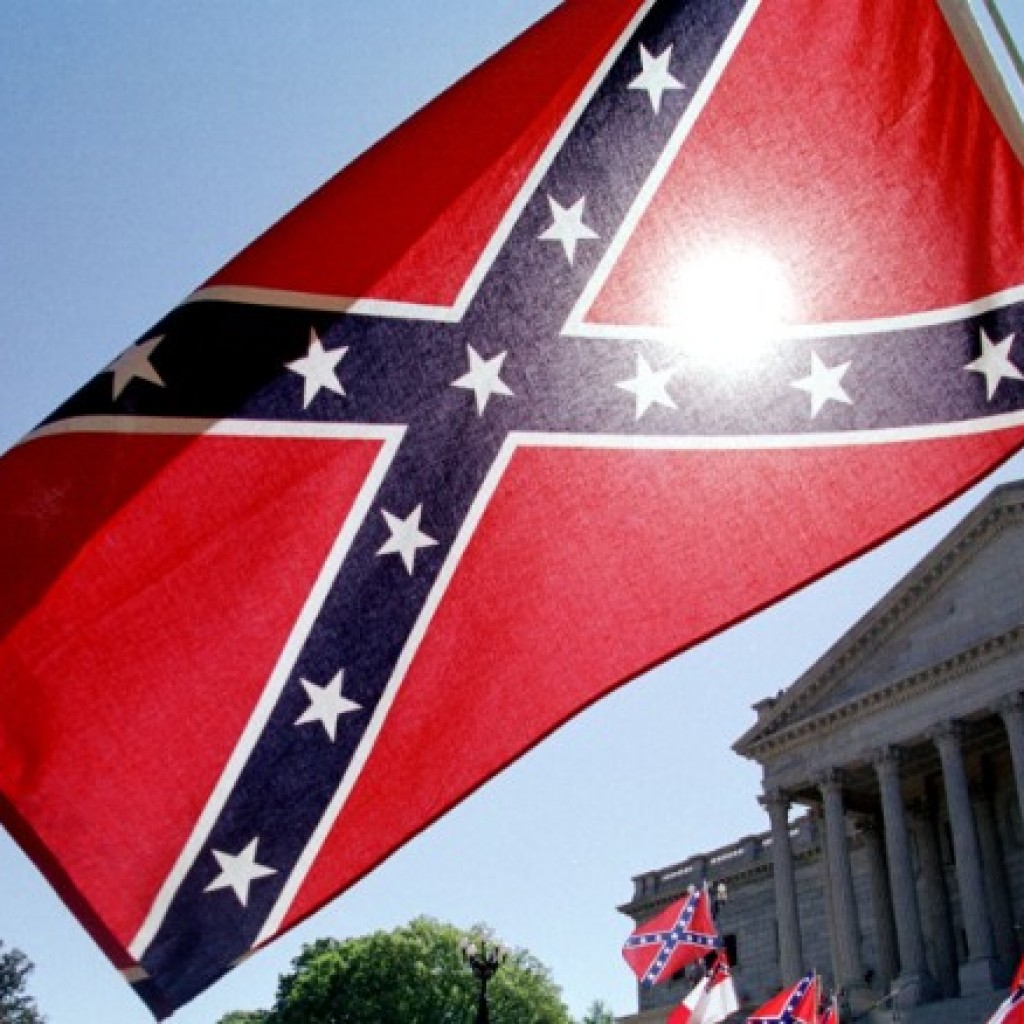

But an on-air radio discussion over South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley’s call to remove the Confederate battle flag from that state’s Capitol was refreshingly civil.

“The people of South Carolina and Mississippi have been subjected to this flag that was not a part of their flag since the Civil War, it became a part of it after the Supreme Court decided to integrate our educational system,” said George Young, an officer with the Jacksonville chapter of the NAACP.

“It’s not like the flag was there all the time. For example, in 1955 Georgia made it a part of their state flag, and other states followed. So to continue to put something before people that is hurtful, to me is just a violation of human rights, not just civil rights. If you want to intentionally hurt me, it doesn’t make sense to me,” he said during an appearance on WJCT’s First Coast Connect.

Presidential candidates are being forced to go on the record about the issue, as protesters continue to mass near the statehouse in Columbia calling for the flag’s removal. This, in the wake of the massacre of nine black churchgoers in Charleston. Confessed gunman Dylann Roof used the Confederate flag to express his white supremacist philosophy, authorities say.

“It is a symbol of pride,” said David Nelson, Commander of Jacksonville’s Kirby Smith Camp 1209 of The Sons of the Confederate Veterans, an organization of direct descendants of Confederate soldiers. “And whether or not the flag is flying or not, it’s not going to stop evil. The flag does not represent what that young man believed it to represent. He was wrong in what he thought and certainly wrong in what he did. We certainly should not blame the emblem.”

2016 GOP presidential candidate Jeb Bush has been quick to point out he ordered the removal of the Confederate flag battle design from Florida’s state Capitol in 2001, an action that did not impress Young.

“To say I removed the flag in Florida 10 years ago — well, if you believe it should be removed in Florida, then shouldn’t it be removed everywhere? Then to come back a week later and say ‘kudos’ to the governor, well why only now are you jumping on this wagon?”

Former Jacksonville City Councilman Matt Carlucci, so often the voice of moderate reason in North Florida public affairs, also had his say.

“I’m sure on my mother’s side I have relatives that fought for the Confederacy,” he said. “But by the same token, the flag resurged during the 1960s as a type of protest. Anything that divides this country I don’t think is good. We should rally around things that build us up as one. And so to fly the flag on public property I just think is not thinking of the whole.”

Reminders of Jacksonville’s Confederate past are everywhere, from the Civil War statue in downtown Hemming Park (facing south, of course) to an actual park named after the Confederacy. As in so many other Southern cities, these discussions can be painful. But the conversation is taking place, across a multitude of platforms.