Citizens Property Insurance Corporation was formed by the Florida Legislature in 2002 for the purpose of serving Florida’s residual property insurance market. Its creation was justified by the argument that middle-income residents have a tough time purchasing insurance in a hurricane-prone state like Florida, and public subsidies were needed to even the playing field for these struggling families. Recent economic research, however, has shown that Citizens is actually a regressive program that disproportionately benefits the wealthy.

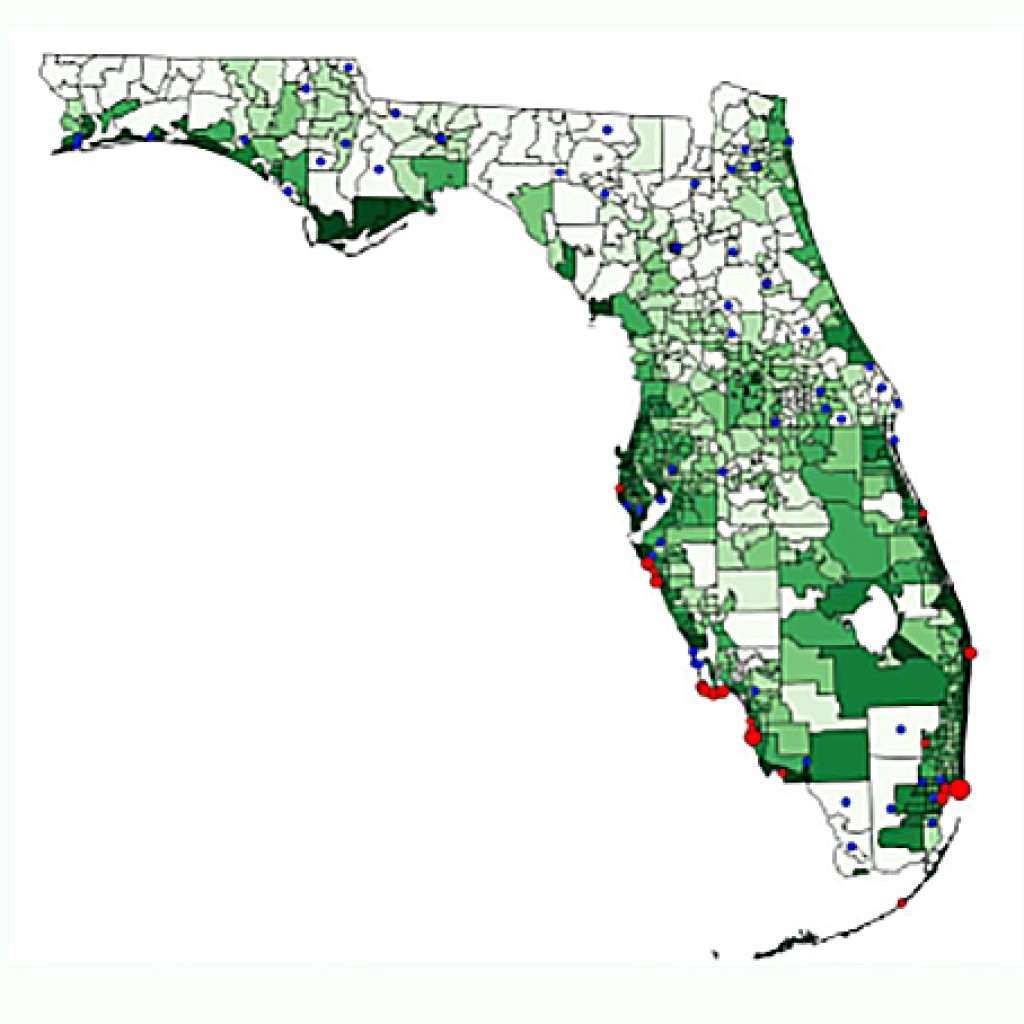

In a 2015 paper, Kyle D. Logue of The University of Michigan and Omri Ben-Shahar of the University of Chicago show that the amount of subsidy a household receives from Citizens increases with wealth. Insurance premiums for more expensive beachside properties are actually the most subsidized, turning the political justification for Citizens’ existence on its head. Figure 1 shows this wealth redistribution with a map from Logue and Ben-Shahir’s paper. The darker shades of green corresponding to more subsidized customers. In fact, lower-risk inland regions often pay higher premiums in order to fund these generous subsidies to affluent coastal homeowners.

Florida’s Office of Insurance Regulation (OIR) is ultimately responsible for setting Citizens’ rates, and their policy of favoring affluent coastal homeowners may get even worse. Citizens recently asked the OIR that they be allowed to increase rates, in part to cover water-loss claims in South Florida. Contrary to Citizens’ own recommendations, the OIR ordered that rates should increase slightly more for low-risk areas, and slightly less for high-risk coastal areas. This rate change may redistribute even more wealth from Florida’s taxpayers and insurance policyholders to Citizens’ wealthy and high-risk customers.

Logue and Ben-Shahir also point out that “the subsidies induce excessive development (and redevelopment) of storm-stricken and erosion-prone areas.” Citizens- subsidized premiums make high-risk properties appear cheaper than a free market would allow, encouraging development where storms pose the biggest threat. This also leaves every taxpayer and insurance policyholder in Florida on the hook to cover damages in the event of a catastrophic storm. As a publicly funded company, Citizens can tap into state funds and extract assessments from other insurance policyholders throughout the state, an advantage not enjoyed by private companies that must operate within their means.

Though efforts to reduce Citizens’ exposure have brought the number of its policies-in-force down from a peak of 1.5 million to fewer than 600,000, it remains Florida’s largest property insurer by customer count.

There is reason to believe Florida would be better off without Citizens. The private market has increased the number of properties it insures as Citizens has reduced its own (see Figure 2), indicating that private insurers are able and willing to serve the residual market. Growth in the private market means property insurance premiums in Florida will more accurately reflect the risk associated with the property. Lawmakers should continue to depopulate Citizens in order to halt its regressive subsidies and allow private insurance companies to encourage safer and less risky development.

Matt Kelly is a researcher for the DeVoe L. Moore Research Center.