Beach Boulevard and Atlantic Boulevard on Jacksonville’s Southside have seen better days.

Their infrastructure — and their buildings — would be eligible for Social Security if they were people.

Meanwhile, the neighborhoods nearby likewise suffer.

Parental Home Road. Hogan Road. Grove Park. The northern stretch of Touchton. Windy Hill.

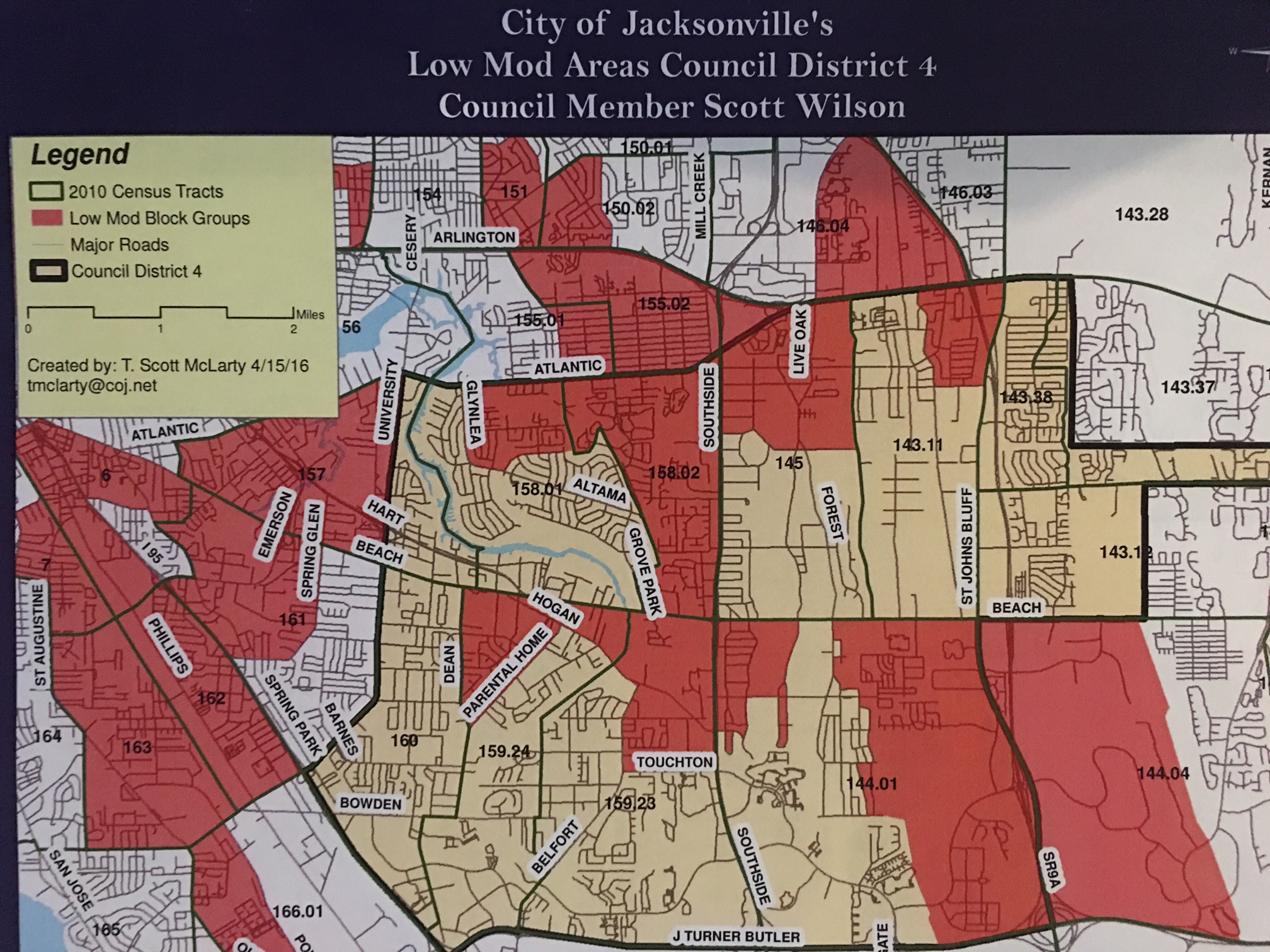

These neighborhoods fall into a netherworld. They clearly are in protracted decline, yet because Jacksonville’s economic development incentives for distressed areas are categorized by census tracts rather than blocks, the formula doesn’t encompass them.

In a meeting of Jacksonville City Council members and other city employees Wednesday, these issues were discussed.

District 4 Councilman Scott Wilson lives off of Parental Home Road. He knows the district very well — before his election last year, he was the assistant to his predecessor.

And he knows the area needs help.

The commercial corridors are in trouble: a hodgepodge of “pawn shops, used car lots, and tire shops,” Wilson said.

Not much viable retail.

Not much visual appeal.

And not much of an economic engine to make these core Southside neighborhoods attractive to homeowners.

Wilson wants redevelopment in his district, but is hampered by municipal codes of yesteryear.

Sixty years ago, these properties were zoned for a type of development that isn’t happening anymore, hampering redevelopment. The issue: “heavy commercial” CCG2 zoning, which Council VP-Elect John Crescimbeni decries as “awful zoning that never should have happened.”

The entire census tracts aren’t affected, per se, which Wilson contends leads to a misunderstanding of the real situation.

The census tract that includes the Town Center and Tinseltown, Wilson said, also has one of the worst neighborhoods on the Southside.

The problem: incentive programs in the city’s toolbox don’t match up with today’s business purposes for these older, declining areas.

“Windy Hill is the poorest neighborhood on the Southside … Sandalwood is not what it once was,” Wilson said, rattling off neighborhoods once the homes of a stable middle class, and now more likely rented to an increasingly transient population disconnected from the investment of ownership.

Yes, this happens on the Southside, just as it does in Durkeeville and Northwest Jacksonville and the Eastside.

And just in those places, the same social ills happen: crime, joblessness, hopelessness.

Despair.

There is plenty of data to look at, of course. And the more detailed the analysis, the more meaningful the data is.

The current approach is more “macro.” The granular analysis, which currently isn’t used in Jacksonville’s economic development policy, would give a better understanding of how many areas in Jacksonville are truly distressed.

As we found out during the Economic Development Incentives Subcommittee meetings earlier this spring, there was some resistance to looking at all the data there is, which led to results that were more palatable for politicians, but less reflective of the real stresses on communities.

A similar phenomenon was observed by Scott Wilson’s assistant, Katie Schoettler, who said her district got shorted on Jacksonville Journey funds, because the calculation was by zip code, rather than by more meaningful data.

There are those who believe such decisions are politically driven.

Yet the meaningful realm is policy.

That’s where people live.

That’s where government can make a difference.

Jacksonville is poised to pass its new economic development incentives policy for distressed communities at the next council meeting.

Whether there will be floor amendments to make it reflect a more thorough picture of the stresses faced remains to be seen.