Naika Venant’s mother vehemently refutes narratives by the state agency in a March 13 report, including suggestion she ‘allegedly’ commented on Facebook Live thread taunting daughter while watching and did nothing; lawyer says agencies ‘abysmally failed’ Naika.

***

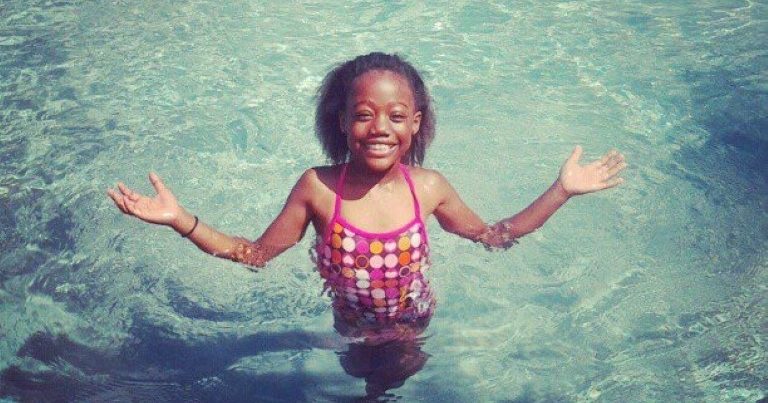

Naika Venant was a girl whose personality had turned from that of a bright and gifted child – despite her naïveté toward adult subject matter – to one of rebelliousness and anger, according to records and her mother.

The dark transition leading her down the path to suicide in January at the tender age of 14 was fraught with complexity, her life taking an unrecoverable nose-dive, her biological mother argued, following the months in 2009 when Naika was repeatedly raped and molested during the first of three tumultuous tours through Florida’s foster-care system in Miami-Dade County.

During a nearly four-hour phone interview Sunday with Gina Alexis, the bereaved mother chronicled her daughter’s life, wanting to clear the air on many issues she claimed were misreported in the press or by the agencies tasked with the safety and well-being of her daughter through the Department of Children and Families (DCF) – Our Kids of Miami-Dade Monroe and the Center for Family and Child Enrichment (CFCE).

Since the early morning hours of Jan. 22, when Naika – medicated on 50 mg of Adderall and 50 mg of Zoloft daily, per a doctor’s directives just weeks before on Dec. 8 – put a scarf around her neck and ended her life, small but significant details have trickled out into the public domain.

There’s a contradiction between DCF’s assertion in the CIRRT (Critical Incident Rapid Response Team) report the teen was in capable hands at the time of her death and facts laid bare in more than 3,500 pages of documents released just two days after the CIRRT report, which include police records, psychological evaluations, foster home placement files and exchanges between a caseworker and Alexis.

On basic thematic levels, there are parallels between the trove of thousands of pages of documents released by DCF – following a judge’s order after The Miami Herald fought the agency in a court of law to do so – and the account described by Alexis during the interview with FloridaPolitics.com on Sunday.

She was frank in discussing her daughter’s gravitation toward age-inappropriate sexual behavior, her attempts at trying to rid her daughter of poor behavior picked up in foster homes when reunited with Naika and the frustration of being re-admitted to a system that controlled their every move and set unrealistic expectations at times.

And Alexis was beholden to Naika’s rebelliousness, she said, which included sometimes lying about abuse to authorities when she wouldn’t get her way or when she was punished because she knew her mother was deathly scared of DCF.

Punishments usually included having her tablet or cellphone taken, which would send Naika into uncontrollable fits – one so bad she ran out of the house and didn’t immediately come back. When Alexis called the police to help her, they found Naika and brought her home. But when Naika got out of the police car, she claimed her mother would beat her again, prompting yet another intrusive DCF investigation, the mother said.

In another instance, Naika burned herself, went to school the next day and told her teacher that her mother did it to her, Alexis said Sunday.

When an investigation followed, they wound up giving polygraphs, Alexis said, and the truth came out that Naika had lied to her teacher and child protection workers.

The mother was absolved of any wrongdoing in that instance.

She described the cycle of dealing with DCF as a “merciless merry-go-round.”

But she readily admits to what introduced them to the child welfare system in the first place.

In early 2009, Alexis came home and caught another 4-year-old girl giving Naika oral sex.

“I whooped her; there’s no denying it,” she said. Alexis lost her temper and pelted Naika with a belt, leaving around 30 lashes all over her body.

It was in Naika’s first foster home following this episode that she was molested and raped by an older foster teen.

The Facebook comment

Much of the child welfare summary part of the CIRRT report focused on Alexis, known then to DCF officials by her maiden surname – Caze.

Following the report’s first two pages – a cover page and a table of contents to the 20-page report – is the executive summary. On the first page of the report’s contents, DCF detailed a comment left under Alexis’s name.

Rather than beginning the report with other standard information in the executive summary, the department chose to feature prominently an “abuse report” made Feb. 9 by an unnamed source – more than two weeks after Naika died, claiming a comment “allegedly” written by Alexis “could be considered mentally injurious to her suicidal child and failed to seek help” for Naika.

The fact DCF stated in two separate paragraphs that “she wrote” the comment, then in the next paragraph of the CIRRT cited it was “allegedly written” by Alexis, both of which contradict each other.

FloridaPolitics.com chose not to republish the comment, having written a story on the topic previously when the CIRRT was released.

And according to Alexis, no one from DCF has contacted her since her daughter’s death to verify the comment, not even to extend an apology. (And she was never notified about the change in dosages of her daughter’s medication on Dec. 8.)

However, based on the comment, DCF elevated their reaction as a department.

“Upon receipt of the abuse report, the special review assignment was reclassified as a Critical Incident Rapid Response Team (CIRRT) response as there was a verified prior report involving the child and her mother within 12 months of Naika’s death,” the report stated

It’s unclear why the suicide of a teen girl on psychotropic prescriptions, who had broadcast it live via social media to a viewership of more than 1,000 people five weeks after another teen girl – in the same area, also with a using a scarf in a shower stall, and both under the care of Our Kids – wasn’t enough in itself to warrant a CIRRT response.

However, DCF did reply to an email by FloridaPolitics.com.

“CIRRT reports include a summary of the call made to the abuse hotline reporting the death of a child due to suspected abuse, neglect or abandonment,” Jessica Sims, DCF spokeswoman, said Monday.

Up to that point, DCF only knew the comment existed, but apparently failed or chose not, to verify its origin.

“They are making me out to be a monster,” Alexis said by phone from Miami, sobbing. “It’s not true.”

She stated the video of her daughter began at approximately 10:59 p.m. and she posted her comment at approximately 1:15 a.m., without knowing Naika was already gone, as she had just begun to receive a barrage of texts from friends telling her to check on Naika through her Facebook page.

“I didn’t taunt her – I didn’t know what she was even doing yet – I thought it was a hoax because when I saw it other people were saying it was fake, so I did, too,” she said. “I still haven’t seen the (video) stream to this day. In the comment, I don’t see a mother saying, ‘Do it,’ I see a mother saying, ‘Don’t – stop,’ because here’s the reality of what can happen if she did do it, and what she needed to be doing instead of playing with Facebook males and females – stick to your books. I would trade places with Naika if God said I could.”

DCF said the death was still under examination.

“The department’s death investigation is ongoing, and coordination with law enforcement continues,” Sims said. “While details are confidential at this time, a report will be posted on the department’s child fatality prevention website upon completion of the death investigation.”

The texts

In a previous paragraph of the executive summary in the CIRRT, it states Naika’s sadness that “her mother didn’t want her back.” According to Alexis, she never gave up custody, and this line is from an exchange between herself and a caseworker named Tramile Barriffe, employed by CFCE.

(It’s unknown if Barriffe is still employed at CFCE. Both CFCE and Jackie Gonzalez of Our Kids did not respond to requests for comment on this or another story.)

Further, the CIRRT report claimed that in the final nine months of Naika’s life custodial parental rights still belonged to Alexis, while guardianship was in the hands of the state. But then the report states, in part, “… for the 22 months that preceded her re-entry into care, Ms. Caze relinquished custody of Naika on April 20, 2016, citing that she no longer wanted the child in her home.”

Alexis said this is a false statement and part of the intent to use her as a scapegoat.

“I would never have given her up – I never did,” Alexis said. “I was expressing my frustration at them for not doing enough. They are making me out to be a horrible mother. I never gave up my rights to her. These are red flags.”

The exchanges referred to in both the CIRRT report and by Alexis are recounted in a series of text messages between Barriffe and the mother on pages 174 through 199 on a section of police report documents – from those the judge ordered DCF to release.

On Jan. 10, Alexis sent Barriffe several texts with screen shots of Naika on Facebook engaging in sexually explicit behavior with other people.

“Please share with co-workers the judge and everyone else involved in this case… Keep the headache y’all created…,” Alexis tells Barriffe in text messages at 9:13 a.m., 1:53 p.m. and 1:56 p.m. “I will let y’all be the judge if who is good or not who been learning and who chooses not to … When in my care there wasn’t none of that she gets worse by second in y’all care …”

Barriffe responds at 3:46 p.m., saying: “Hi … I try not to make every phone call that I make to you about an incident because usually they are not good reports. I wanted to see you that’s why I have been calling to meet up with you. At this point, I let my supervisor know everything because the case isn’t moving forward. I spoke to Niaka (sic) about all the things she has posted up and that will be up to her to make better decisions. (…) I can’t tell you if all the things she posted is something she is engaging in. (…) She has to be the one to practice better decision even with all that is being provided to her.”

Alexis responds, in part: “Naika y’all problem for her to play innie minnie miny mo with through homes I’m done with the games may God be with you all… Bless”

Barriffe goes on to say there would be a new case worker handling Naika, something Alexis cited as a problem throughout the 28 total months her daughter spent in foster care, as every three to four months they would have to acclimate to a new caseworker, making continuity “impossible,” she said.

“The department contracts with community-based care lead agencies and the lead agencies contract for case management,” Sims said. Accordingly, the department cannot speak directly to actions taken by case managers.

Placing blame by negative portrayal?

Howard Talenfeld, a child advocacy attorney and president of Florida Children First, said the caseworker was making an unrealistic presumption.

“This girl was 14 with therapeutic needs, bouncing from placement to placement on psychotropic medication, and this caseworker expects her to be making mature decisions on her own?” Talenfeld said by phone from Ft. Lauderdale Saturday. “The caseworker basically threw her hands up in the air and said, ‘I’m done.'”

Barriffe was transitioning from the office, according to DCF.

“The records indicate that the child’s case manager was changed due to the need to work towards transitioning to independent living/extended foster care,” said Sims, the department’s spokeswoman. “Also, as documented in the case notes, it is our understanding that the case manager communicated directly with the child regarding her social media use.”

That shouldn’t have mattered, in Talenfeld’s view. The placement was wrong, he said.

“Naika shouldn’t have been anywhere near a cellphone or the internet,” he said. “It looks like the private agencies involved are trying to deflect the responsibility of providing safe and therapeutic care for Naika and are now trying to blame Ms. Alexis. They’re responsible for the placement of foster care – they have abysmally failed in doing it in this case, and she had severe therapeutic needs.”

With reference to the rapes and sexual abuse in the foster home from 2009 by a then-15-year-old boy named Tevin (an adult now): DCF claimed in the CIRRT report, which was released two days before the 3,500-plus pages of confidential case history, DCF stated, “Naika was placed there and had no prior incidents of inappropriate behavior, nor any subsequent incidents following this allegation.”

Then DCF claimed in the CIRRT report a medical evaluation at that time from a child protection team didn’t find evidence consistent with rape or molestation. The very next sentence switches subjects, commenting how the mother and daughter became “hostile,” about the reasons bringing them into contact with DCF in the first place.

It wasn’t clear if DCF went back and thoroughly examined the case files on the 2009 situation as a part of its research in issuing the CIRRT report, as Alexis said she took Naika to Charlee, in Miami, a now-defunct facility providing services to abused children.

“It’s a lie,” Alexis said. “She had a UTI (urinary tract infection) and I was like, ‘Wait a minute,’ so I took her to Charlee because I said, ‘DCF’s got to tell me something.’”

She described how a doctor with Charlee corroborated the sexual assault. A previous caseworker named Tatiana Ashley, whose name appeared in several documents examined by FloridaPolitics.com, helped facilitate the appointment at Charlee.

Alexis claimed officials were prepared to offer compensation for the abuse that had taken place, but she said she wanted to consult with a lawyer first.

“And even before until I left the elevator in the building that they erased the whole thing once I said I wanted to talk to a lawyer,” Alexis said, making a reference to her belief agency officials were getting rid of any findings from Naika’s medical exam. “They’ve covered it up ever since. The rape happened, and they just keep covering it up, trying to place blame on me.”

Talenfeld, the lawyer, wants to know why Naika was placed in a home with two other foster children, all three sleeping in one bedroom. He also pointed out that the foster mother was brand-new and was not supposed to have children with behavioral or mental health issues.

“Was the foster mother specially trained to handle special needs children on medications?” he asked. “Did she know what signs to look for in mood, like depression? Was there internet in the home?

“There are a shortage of therapeutic placements for this kind of children who are seriously emotionally disturbed,” the attorney continued. “There are a lot of questions, no easy ones.”

FloridaPolitics.com attempted to get a comment from key state legislators on the Florida Senate’s DCF oversight committee without success.

One comment

Voncile

March 28, 2017 at 10:49 am

I put no faith in Florida DCF. I sat with my grand daughter once and gave a detailed report of what was going on in her family background. What I later read in that report was nothing like what was discussed in the meeting. IMO, DCF needs to be investigated and people fired!! If someone were to ask me, I’d say they are NOT protecting the helpless children, only their paychecks!!

Comments are closed.