Mention of a wildlife officer in Florida, and many think of someone who checks your fishing license.

Mention of a wildlife officer in Florida, and many think of someone who checks your fishing license.

But the protection and dangers of the job are far beyond that, former game warden Bob H. Lee told a packed auditorium Thursday at Florida Southern College in Lakeland.

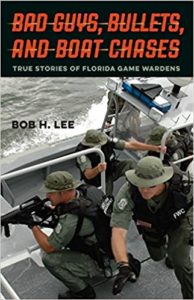

Lee is the author of “Bad Guys, Bullets and Boat Chases — True Stories of Florida Game Wardens.” It is a book of the stories of wildlife officers and their duties ranging from high-speed boat chases to gunfights and poaching.

“There are over 1 million city, state and federal law enforcement officers in the United States. There are only 6,000 wildlife officers, often working alone in remote areas without backup,” Lee said.

His appearance was part of the lecture series of the Lawton Chiles Center for Florida History.

It was the public’s general lack of understanding of these special law enforcement officers that prompted Lee to write his first book, “Backcountry Lawman.”

His first memorable episode in his career, Lee told his audience, was as an eighth month rookie on patrol alone at midnight on the Ocklawaha River when his boat sank. Grabbing a fuel can he began floating in the direction of a landing in the river.

“Now this was in 1978 after 25 years of a ban on alligator hunting. The river was full of gators,” he said.

During a two-mile or more float toward the landing, a bull gator jumped into the water so close it rattled the gas can. He arrived at the landing where four men were drinking around a campfire. Lee ended up driving his “rescuers” the next morning because they were too intoxicated to drive.

“That story had many layers to it. I like to write stories in layers,” he said.

But threats to wildlife officers are from more than animals.

He recalled two officers in a helicopter chasing two suspected deer poachers who were in a Piper Cub. The plane charged at the helicopter trying to crash it. The officer piloting the helicopter, a former pilot in Vietnam, maneuvered under the plane stealing its wind, Lee said, causing it to drop to the ground where arrests were made.

Poaching of baby alligators and passing them through licensed alligator farms is a major issue. Lee noted that several years ago a bust was made on poachers who captured 17,000 baby alligators to be sold for $8 apiece.

“It is now $28 a piece,” he said.

Baby alligators hatched in licensed farms can be sold legally, so poachers have found some perhaps less than honest gator farmers who mix in the poached baby gators. But high technology is now used by the Florida Wildlife Commission: DNA testing.

Technology also shows the worsening problem of the Burmese Pythons in the Everglades, Lee said in answer to a questioner from the audience. Pythons released either accidentally or on purpose are a growing problem to the ecosystem of South Florida, so much so that they will never be eradicated.

By tracing a pathogen carried by cotton rats found in captured Pythons, researchers are finding more and more being eaten by the snakes indicating that they may have greatly diminished the population of other native animals in the Everglades.

“That is the one animal where there is no license requirement,” he said of pythons.

The state even sponsors an annual python hunt, although anyone can hunt pythons any day of the year.

“Anyone who wants an Indiana Jones moment can hunt them,” he said.

But it is all for control. There are now too many for eradication.

Florida’s has a proper amount of game wardens. With somewhere a little over 800 members, it is the state with the most conservation law enforcement officers. Even larger than Texas and California wardens, Lee said.

The problem, he said, is the lack of experience due to retirements under the DROP Program. When signing up for the program, employees must leave after five more years of service

“There are fewer experienced officers because of DROP,” he said.