Ron Wen knew Elizabeth Warren was running for president, but not much else.

“We hear one or two things about ‘Medicare for All,’” the 52-year-old technical marketing professional said about Warren’s universal health care plan as he waited for a town hall with the Massachusetts senator to begin inside a packed high school gym in North Carolina’s capital. “You always get the sound bites. You need to just go deeper.”

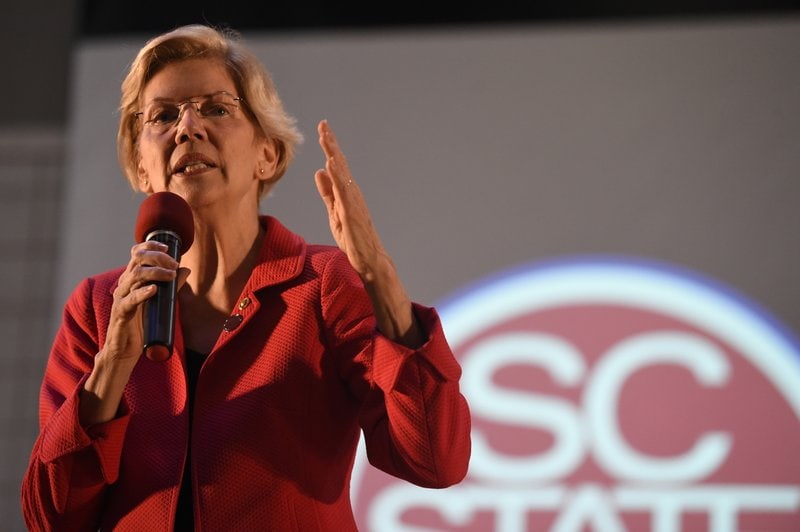

Warren has risen in the polls for months, among the front-runners now in the 2020 Democratic primary and finding herself portrayed by comedian Kate McKinnon on “Saturday Night Live.”

For many people, however, Warren is still a relative unknown, even among those who have begun paying closer attention with voting beginning in under three months.

Nearly one-quarter of Americans say they don’t know enough about Warren to have an opinion, according to a recent poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. The same poll shows that just about 1 in 10 Americans say they don’t know enough about rivals Joe Biden or Bernie Sanders.

Biden was a two-term vice president and Vermont Sen. Sanders sought the White House four years ago, when he climbed from a virtual national unknown to credible challenger to Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. Still, even among Democrats, more say they don’t know enough about Warren, 16% versus 9% for Biden and 8% for Sanders, according to the poll.

An October Quinnipiac University poll showed 23% of Americans saying they hadn’t heard enough about Warren, including 18% of Democrats. That was down from 31% of all Americans and 28% of Democrats in Quinnipiac’s December 2018 poll, but still shows she has work to do to boost her name recognition.

It’s both a challenge and an opportunity for Warren. She must still introduce herself to voters, but, perhaps unlike some of her competitors, there’s also room to increase her support.

It’s a counterintuitive situation for someone who has become known lately for attracting giant crowds in places like Seattle, St. Paul, Minnesota and Manhattan. Warren’s campaign acknowledges that she trails Biden and Sanders in name recognition. But Warren says that’s why North Carolina is the 28th state she’s visited as she tries to build a grassroots movement nationwide. That often means staying behind at events for hours and taking 75,000 “selfies” with attendees.

Warren drew around 3,500 people in Raleigh, a raucous crowd that thunderously stomped its feet on the wooden bleachers. Still, she was in the Research Triangle, where many people are college-educated, relatively affluent and more likely to be Democratic-leaning — a key center of support for progressive Democrats such as Warren.

“She has amazing policies, but I think what happens with a lot of people is they aren’t looking at the specifics of policy and they vote based on emotion,” said Premi Singh, a 40-year-old high school English teacher from Morrisville, outside Raleigh. Singh said that, like Clinton in 2016, Warren may face a tougher climb to make a personal connection with voters because she’s a woman who might be easily dismissed as overly professorial.

“We’ve gotten so used to reality television, not just with Donald Trump but with everything,” Singh said. “Everything has to be exciting and everything has to be so filled with drama that our capacity to handle substantive discussions is more difficult.”

On “SNL,” McKinnon plays up Warren’s wonkish tendencies but also uses physical comedy to spoof the candidate’s high-energy approach to town halls, where she runs on stage and implores the audience to stay positive.

“I am in my natural habitat, a public school on the weekend,” McKinnon’s Elizabeth Warren crowed with kicks and air punches to open a recent episode.

The real-life Warren used parts of a McKinnon sketch spliced with actual footage of the candidate calling to thank small donors in an online ad she tweeted to her 3.5 million followers.

Name recognition could be especially important in North Carolina, which holds its 2020 primary on Super Tuesday in March, three days after South Carolina hosts the South’s first primary. It’s also an important general election battleground state. It went for Barack Obama in 2008 but voted Republican during the 2012 and 2016 presidential campaigns.

Some people acknowledged knowing about Warren, but not for reasons she’d favor.

At an Exxon station across the street from Warren’s rally, a man gassing up his pickup mumbled something about “the Pocahontas lady,” referring to the slur that Trump has used to scoff at the controversy over Warren’s past claims of Native American heritage. Inside a nearby McDonald’s, some diners nodded when asked if they knew who Warren was but couldn’t name her home state.

Before appearing in Raleigh, Warren visited North Carolina A&T State in Greensboro, the nation’s largest historically black university. Though she filled most of a campus auditorium, Brandon Rucker, a junior studying journalism who hails from nearby Winston-Salem, said he was surprised the crowd wasn’t larger.

“I think people know who she is but I think they still have questions,” Rucker said.

Kenon Lattimore, a senior political science major with a “Black Lives Matter” pin, didn’t wait for a selfie with Warren afterward because he said he prefers Sanders, for now.

“A lot of times, I feel like her platform points are coming from Bernie Sanders and it’s basically just being presented in a different way,” Lattimore said.

Nicole Ward Quick, Democratic Party chairwoman in Guilford County, which includes Greensboro, agreed that name recognition isn’t the biggest problem Warren faces.

“Our progressives know her. I would say that she’s going to be a tough sell for North Carolina overall,” she said. “I’m a fan of hers, but I have concerns. I don’t know if the rest of the state will elect a progressive. I don’t know if they’d even vote to elect a woman.”

__

Republished with permission of The Associated Press.