A team of scientists jostled for a view of the lab dish, staring impatiently for the first clue that an experimental vaccine against the new coronavirus just might work.

After weeks of round-the-clock research at the National Institutes of Health, it was time for a key test. If the vaccine revs up the immune system, the samples in that dish — blood drawn from immunized mice — would change color.

Minutes ticked by, and finally they started glowing blue.

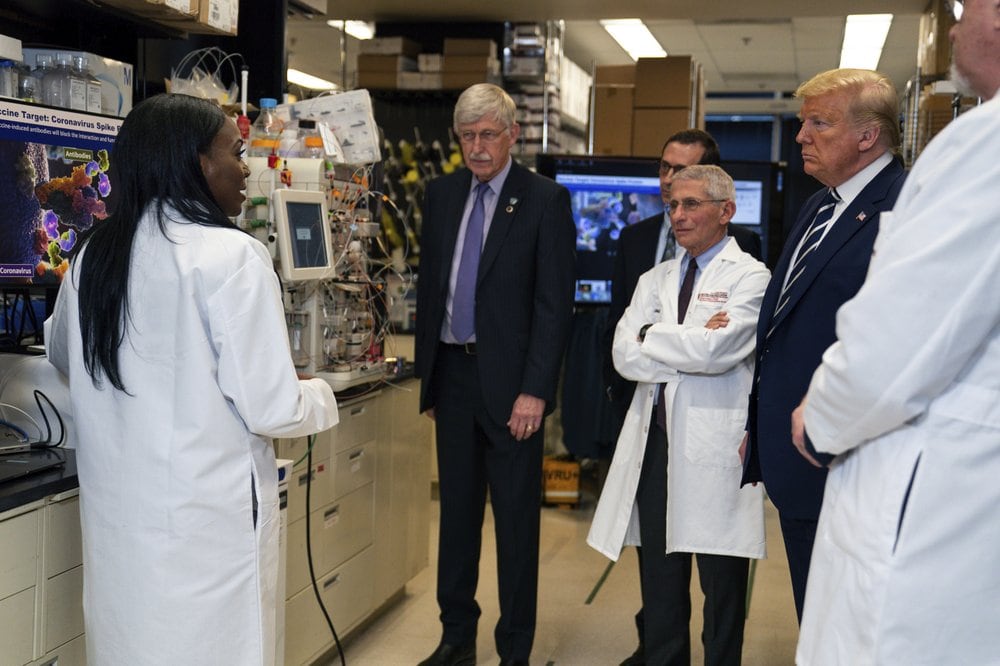

“Especially at moments like this, everyone crowds around,” said Kizzmekia Corbett, an NIH research fellow leading the vaccine development. When her team sent word of the positive results, “it was absolutely amazing.”

Dozens of research groups around the world are racing to create a vaccine as COVID-19 cases continue to grow. Importantly, they’re pursuing different types of vaccines — shots developed from new technologies that not only are faster to make than traditional inoculations but might prove more potent. Some researchers even aim for temporary vaccines, such as shots that might guard people’s health a month or two at a time while longer-lasting protection is developed.

“Until we test them in humans we have absolutely no idea what the immune response will be,” cautioned vaccine expert Dr. Judith O’Donnell, infectious disease chief at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center. “Having a lot of different vaccines — with a lot of different theories behind the science of generating immunity — all on a parallel track really ultimately gives us the best chance of getting something successful.”

First-step testing in small numbers of young, healthy volunteers is set to start soon. There’s no chance participants could get infected from the shots, because they don’t contain the virus itself. The goal is purely to check that the vaccines show no worrisome side effects, setting the stage for larger tests of whether they protect.

First in line is the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle. It is preparing to test 45 volunteers with different doses of shots co-developed by NIH and Moderna Inc.

Next, Inovio Pharmaceuticals aims to begin safety tests of its vaccine candidate next month in a few dozen volunteers at the University of Pennsylvania and a testing center in Kansas City, Missouri, followed by a similar study in China and South Korea.

Even if initial safety tests go well, “you’re talking about a year to a year and a half” before any vaccine could be ready for widespread use, stressed Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

That still would be a record-setting pace. But manufacturers know the wait — required because it takes additional studies of thousands of people to tell if a vaccine truly protects and does no harm — is hard for a frightened public.

“I can really genuinely understand everybody’s frustration and maybe even confusion,” said Kate Broderick, Inovio’s research and development chief. “You can do everything as fast as possible, but you can’t circumvent some of these vital processes.”

Behind the scenes in NIH’s lab

The new coronavirus is studded with a protein aptly named “spike” that lets the virus burrow into human cells. Block that protein, and people won’t get infected. That makes “spike” the target of most vaccine research.

Not so long ago, scientists would have had to grow the virus itself to create a vaccine. The NIH is using a new method that skips that step. Researchers instead copy the section of the virus’ genetic code that contains the instructions for cells to create the spike protein, and let the body become a mini-factory.

Inject a vaccine containing that code, called messenger RNA or mRNA, and people’s cells produce some harmless spike protein. Their immune system spots the foreign protein and makes antibodies to attack it. The body would then be primed to react quickly if the real virus ever comes along.

Corbett’s team had a head start. Because they’d spent years trying to develop a vaccine against MERS, a cousin of the new virus, they knew how to make spike proteins stable enough for immunization, and sent that key ingredient to Moderna to brew up doses.

How to tell it’s a good candidate to test in people?

Corbett’s team grew spike protein in the lab — lots of it — and stored it frozen in vials. Then with the first research doses of vaccine Moderna dubbed “mRNA-1273,” the NIH researchers immunized dozens of mice. Days later, they started collecting blood samples to check if the mice were producing antibodies against that all-important spike protein. One early test: Mix the mouse samples with thawed spike protein and various color-eliciting trackers, and if antibodies are present, they bind to the protein and glow.

Corbett says the work couldn’t have moved so quickly had it not been for years of behind-the-scenes lab testing of a possible MERS vaccine that works the same way.

“I think about it a lot, how many of the little experimental questions we did not have to belabor” this time around, Corbett said. When she saw the first promising mouse tests, “I felt like there was a beginning of all of this coming full circle.”

Inovio’s approach

Inovio’s approach is similar — again using genetic code, in this case packaged inside a piece of synthetic DNA that acts as the vaccine. One advantage Broderick cites for a DNA approach is that unlike many types of vaccines, it may not need refrigeration.

A MERS vaccine that Inovio designed the same way passed initial safety studies in people, paving the way for testing the new COVID-19 vaccine candidate. Inovio is doing similar animal testing to look for presumably protective antibodies.

While it gets ready for human safety tests, Inovio also is prepping for another piece of evidence — what’s called a challenge study. Vaccinated animals will be put in a special high-containment lab and exposed to the new coronavirus to see if they get infected or not.

Placeholder vaccines?

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals is exploring a different approach: simply injecting people with coronavirus-fighting antibodies instead of teaching the body to make its own. This method could provide temporary protection against infection or work as a treatment for someone already infected.

Regeneron vaccinated mice genetically engineered to make human antibodies. From small blood samples, researchers culled hundreds of different antibodies, and now they’re teasing out which seem most potent against that notorious spike protein, said Christos Kyratsous, Regeneron’s chief of infectious disease research.

Regeneron developed this “monoclonal antibody” approach as a life-saving treatment for Ebola. Last year, it performed a successful safety test of experimental antibodies designed to fight MERS.

The difference between using antibodies as a treatment or a vaccine? Low-dose shots in the arm every few months might give enough antibodies to temporarily ward off infection, while treatment likely would require far higher doses delivered intravenously, Kyratsous said. Regeneron is pursuing both, and hopes to begin first-step safety testing in early summer.

“The antibodies are the same,” he said. “We would like to have an antibody that is as flexible in administration as possible.”

Whichever of these approaches, or others in the pipeline, pan out, NIH’s Corbett said scientists one day hope to have vaccines on the shelf that could be used against entire families of viruses. One frustration when scientists have to start from scratch is that outbreaks too often are waning by the time vaccine candidates are ready for widespread testing.

“This is the fastest we have gone,” Fauci said of the NIH’s vaccine candidate, although he warned it might not be fast enough.

Still, he called it “quite conceivable” that COVID-19 “will go beyond just a season, and come back and recycle next year. In that case, we hope to have a vaccine.”

___

Republished with permission from the Associated Press