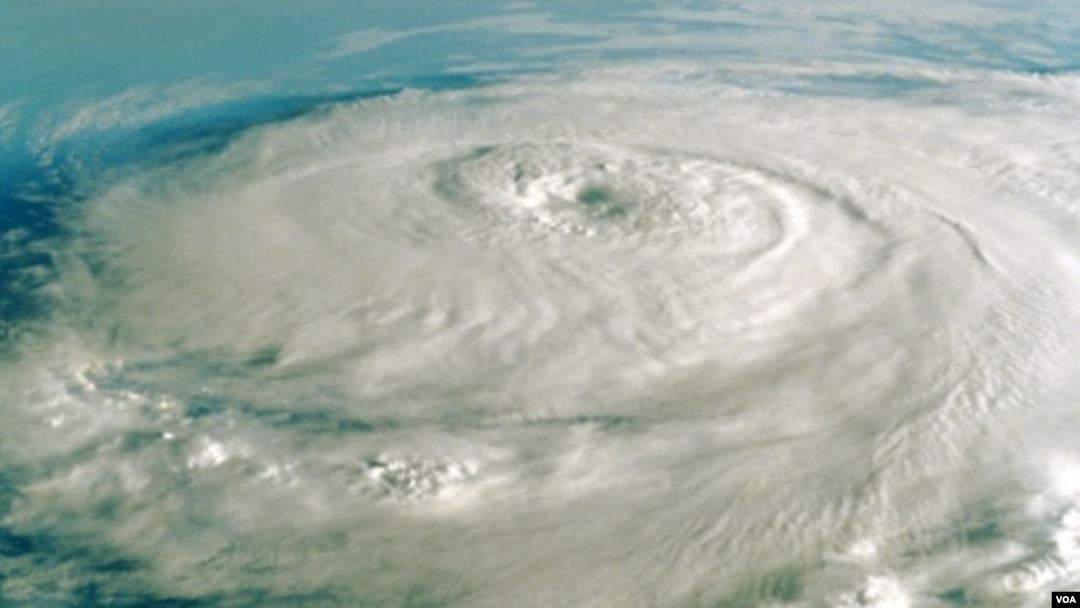

This week, Tropical Storm Beta became the ninth named storm to make landfall in the mainland United States during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, tying a record that stood for over 100 years — since 1916.

This on the heels of Hurricane Sally soaking parts of the Gulf Coast with over two feet of rain, causing nearly $30 million in damage in Florida alone.

These storms, and this record-breaking hurricane season, serve as important reminders of the need to limit the impacts of climate change and build resilience across Florida and the nation.

It is particularly tragic that this hurricane struck at a time when the COVID-19 infection rates are still high. Government leaders must continue to account for coronavirus in planning for hurricane season, which continues through November, balancing the risk associated with evacuations and shelters. In addition, it’s important that Florida’s leaders recognize the need for a long-term resilience plan for future hurricane seasons and climate change, as many have begun to do.

Our coastal state is at significant risk from both more intense hurricanes and sea-level rise. Understanding the risks to life and property is crucial for residents to make wise decisions about reducing risk. Planning for the impacts of climate change and sea-level rise includes augmenting natural infrastructure such as oyster beds and mangroves and elevating homes.

Every $1 spent on disaster mitigation saves $6 in disaster recovery. A recent study found that a square kilometer of wetlands is worth approximately $1.8 million a year on average in storm protection. The study also found that Florida could have reduced damages by $430 million if it had maintained wetlands where Hurricane Irma made landfall.

As if further evidence were required to substantiate Florida’s need for enhanced coastline protection, consider the fact that 20 of the 23 storms this year through September 21 had their earliest formation date on record.

Increasing renewable power, such as solar, and distributed energy could help speed future storm recovery in Florida. The City of Coral Springs deployed solar-powered traffic lights while its electrical grid was down following Hurricane Imra and microgrids of solar-plus-storage at emergency shelters can make sure residents.

According to the National Hurricane Center, the average formation date of the Atlantic’s 8th named storm is Sept. 24 for the years spanning 1966 to 2009. We are now 15 named storms — with 10 formed in September alone. The previous record was eight — all occurring this century (2002, 2007 and 2010).

The unprecedentedness of the 2020 hurricane season abounds.

So far, nine named storms made landfall in the U.S., four of which were hurricanes. On Sept. 14 there were five active storms in the Atlantic at one time—only the second time on record. And on Sept. 18, three named storms formed in the Atlantic over a period of only six hours.

This hurricane season is a clear warning that we need to build coastal resilience across the state of Florida.

Our state is at its most resilient when we take a comprehensive look at the risks, plan for the worst and hope for the best. That is how we govern here in Florida and there is no question that this approach has served us well.

Taking advantage of the state’s natural resources to protect our shores, such as building more mangrove islands, has a triple-bottom-line benefit: protecting inland communities from offshore threats, increasing wildlife and water ecology, and reducing the long-term costs associated with building and maintaining gray infrastructure.

That’s not just smart science, it’s smart policy.