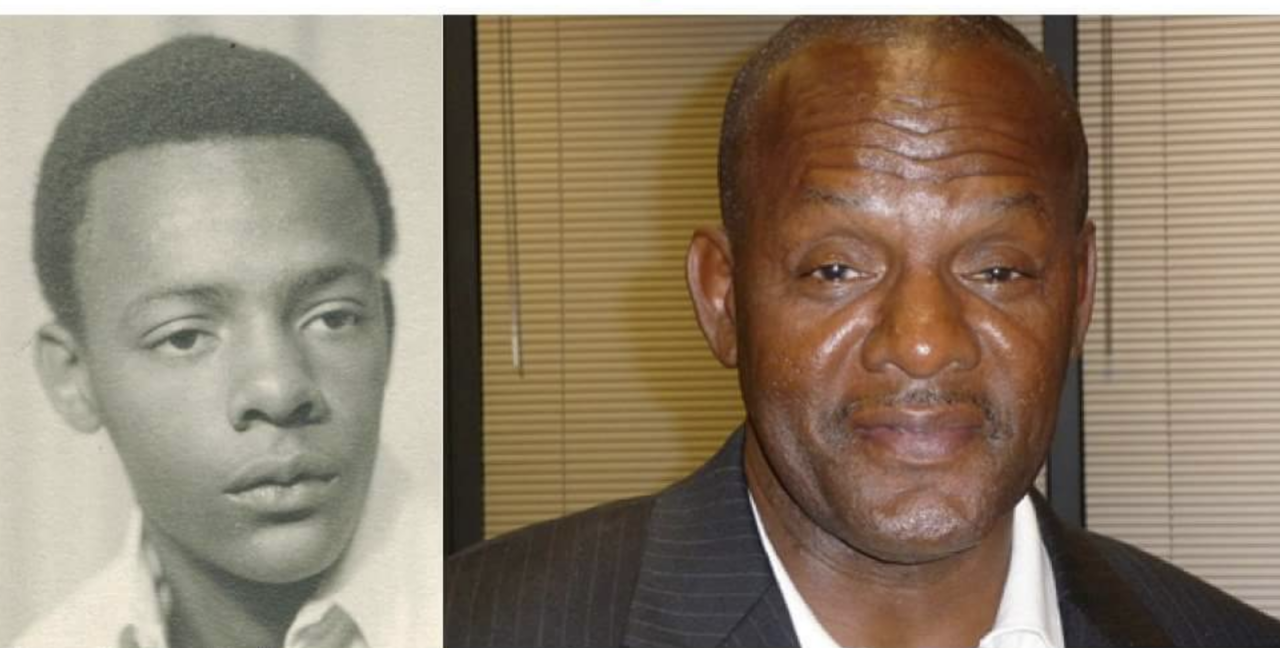

For more than a decade, a Florida man who was tried twice for the same crime and imprisoned for nearly four decades has sought compensation from the state for the time he lost. He’ll get another chance at receiving $1.9 million next year.

Democrats Sen. Shevrin Jones of West Park and Rep. Joseph Geller of Aventura filed twin bills (SB 54 and HB 6503) this month that, if approved during the 2022 Legislative Session, would direct the state’s Department of Financial Services to pay Barney Brown.

Jones’ bill is classified as a “claim” bill or “relief act,” as it is intended to compensate a person or entity for injuries or losses caused by the negligence or error of a public officer or agency.

Such bills often arise when appropriate damages due to a person or entity exceed what’s allowable under Florida’s sovereign immunity laws, which protect government agencies from costly lawsuits by capping payouts without legislative action at $300,000.

In September 1970, a jury in the 11th Judicial Circuit Court of Miami-Dade voted 7-5 to convict Brown of rape and robbery. Brown had been a suspect in two rape cases within the span of six months. According to a 2011 timeline by the Sun-Sentinel, police said his fingerprints matched those left at both crime scenes.

Even though he pleaded guilty to one of the two cases, Brown maintained he was an innocent railroaded into an unjust conviction. He said he was beaten so badly while under interrogation that he still can’t see out of his right eye.

The court nonetheless sentenced him to life in prison. Despite being just 14, he stood trial as an adult.

Just five months before, however, a juvenile court tried him for the same crimes. During that trial, charges against him and two co-defendants were “dismissed without prejudice.”

That made the second trial clearly in conflict with the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution’s “double jeopardy” clause, which protects citizens from being tried for the same crime twice.

Brown spent most of the next 38 years behind bars. He was briefly released, but he was sent back to prison for a parole violation after being accused of robbing a car salesperson in 1983, a crime for which he was later acquitted after a judge found prosecutorial misconduct. But he was still kept in prison.

Brown also was convicted twice for weapon possession while incarcerated. The crimes added 15 years to his sentence.

While serving time, Brown acquired his high school diploma and a college degree. He tried for years to exonerate himself, but his efforts repeatedly ran into legal roadblocks.

Then lawyers Benedict Kuehne and Susan Dmitrovsky took up his case, which went before Miami-Dade Judge Antonio Marin. Marin ruled Brown’s case to be “a clear example of a grievous constitutional double jeopardy violation,” adding: “His incarceration within Florida’s prison system for most of his adult life should never have taken place.”

Marin vacated Brown’s sentence and the conviction from Brown’s guilty plea on Sept. 19, 2008. Six days later, at 53, he was a free man.

Florida’s Victims of Wrongful Incarceration Compensation Act entitles people wrongly imprisoned in the state to $50,000 for every year they spent unjustly imprisoned. Under other circumstances, that would clear Brown to receive $1.9 million.

However, due to the state’s “clean hands” provision, which requires an otherwise qualifying person not to have any other felony conviction on their record, Brown is technically not entitled to compensation.

In 2011, Brown told the South Florida Times he wasn’t worried about the money even though he had filed for compensation.

“My only concern is that those who come after me won’t have to face this dilemma, this type of injustice,” he said at the time.

But in the years since, several Democratic Florida lawmakers have taken up Brown’s cause, including Christopher Benjamin of Miami Gardens and Sen. Perry Thurston of Plantation.

Jones told Florida Politics he hoped to finally secure for Brown, who is now in his late 60s, some recompense for the time he’ll never get back.

“I will have to sit down with some of my colleagues who are legal scholars to figure out what is the best way to do address it,” he said Monday. “It’s been an uphill battle because of the nuances of this case, but that doesn’t mean that Mr. Barney is not owed what he’s owed.”