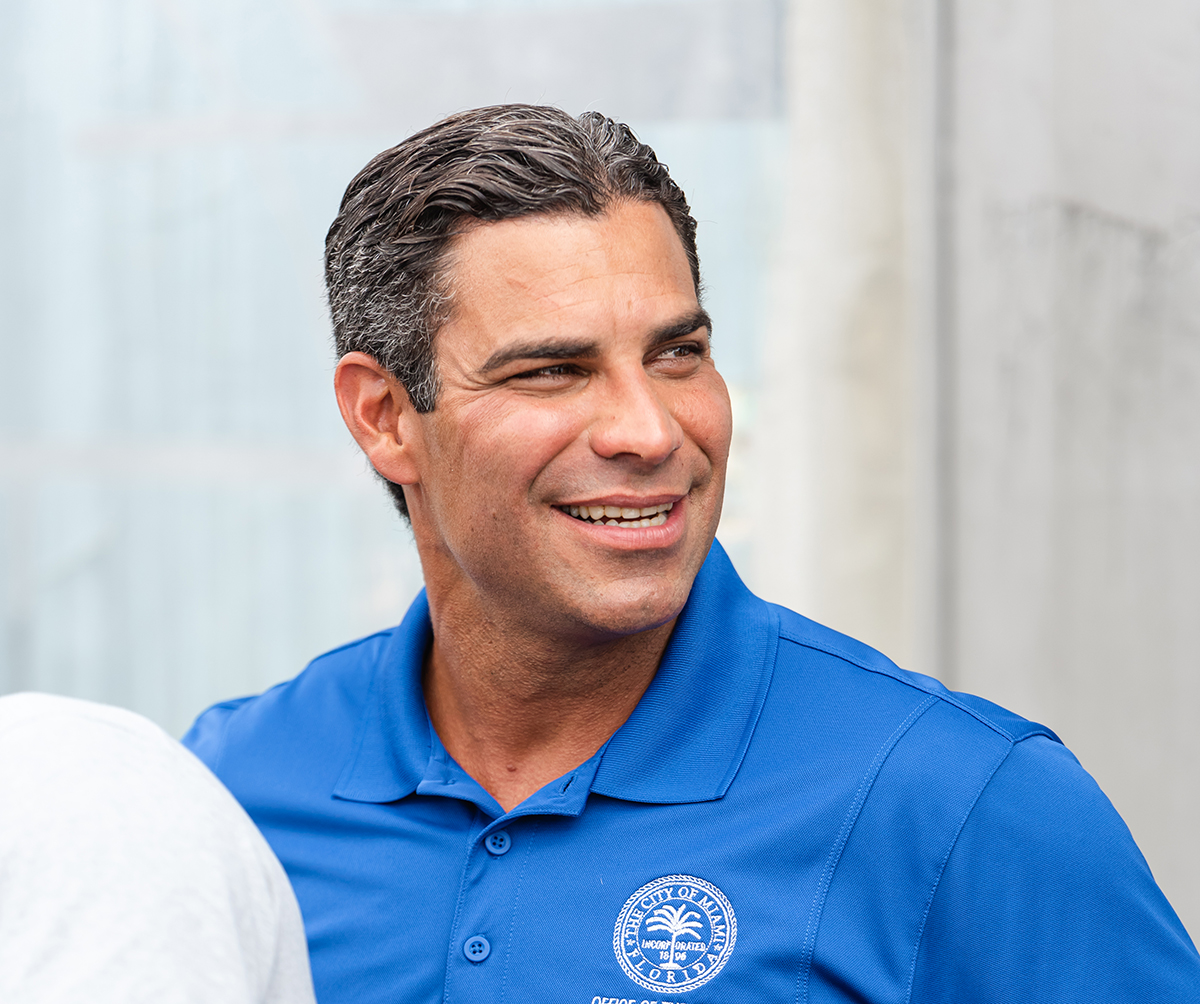

Miami Mayor Francis Suarez again left his opponents in the dust with fundraising between Sept. 1 and Oct. 15, pulling in $875,000 in the final stretch of a race where no true threat to his reelection emerged.

As of Oct. 15, Suarez held more than $4.8 million between his campaign and political committee, Miami For Everyone.

Suarez’s four challengers — digital sports show producer and podcaster Maxwell Martinez; former call center representative and University of Miami student Marie Exantus; recently arrested private investigator Frank Pichel; and mystery candidate Anthony Dutrow — hold less than $10,000 combined, or about 1% of what Suarez has on hand.

Suarez received around 550 donations since the beginning of last month. Of those, more than a third came from the real estate, development and engineering sector. Many lawyers, lobbyists and law firms, as well as a multitude of bigwigs, also pulled out their checkbooks.

Noteworthy donors included former Miami-Dade County Mayor Alex Pinelas, current Pinecrest Mayor Joseph Corradino’s engineering firm, The Corradino Group, and NFL Super Bowl champ-turned broadcast analyst Jonathan Vilma. All gave $1,000.

Former Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine also gave $1,000. His company Royal Media Partners, the onboard media partner of Royal Caribbean Cruises, contributed $5,000.

Former Rep. José Félix Díaz donated $2,000. Alice Bravo, who left her post last year as director of the Miami-Dade Department of Transportation and Public Works for a job with frequent county consultant WSP USA, gave $500.

Suarez got $25,000 from Sunset Opportunities B2 LLC, which runs South Miami mall The Shops at Sunset Place. Miami-based real estate and luxury hospitality investment and development firm Gencom gave $20,000. The company’s vice president and CFO, Donald McGregor and Thomas Bezold, respectively, gave $1,000 apiece.

Greenview Courtyard Inc., run by Philippe Harari of Miami Beach-based Aquablue Group, gave $15,000. Sunny Isles Beach-based Dezer Development, whose lead, Gil Dezer, received an OK last year to redevelop the Intercoastal Mall in North Miami Beach, donated $10,000.

Other donors from the sector included Miami-based firms Ortus Engineering, which gave $10,000; Downright Engineering Corp., which gave $5,000; and ROVR, a local development firm whose slogan is “The Evolution of Miami’s Skyline,” which gave 3,500.

What the telecommunications industry lacked in presence on Suarez’s ledger it made up for in impact. Suarez’s biggest gift, a $100,000 check, came from TriStar Investors, a wireless operator of cell towers operating under the umbrella of Houston-headquartered communications infrastructure and real estate giant Crown Castle.

Fort Lauderdale-based Hotwire Communications gave $50,000. And Comcast Corp. donated $10,000.

Despite being America’s de-facto cryptocurrency Mayor, Suarez’s yield from the tech sector was modest over the last month and a half.

Rideshare company Uber contributed $5,000. Donations of $1,000 came in from Brad Garlinghouse, CEO of cryptocurrency and online pay network Ripple; Tal Eidelberg, CEO of physician scheduling software company Intrigma; Jeremy Arditi, chief commercial officer for ad media platform Teads; and Joey Levy, the president of digital sports betting company Simplebet and a co-founder of Miami-based early-stage tech startup investment fund 305 Ventures.

Other contributions included $20,000 from conservative philanthropist Jay Faison, who runs ClearPath, a nonprofit aimed at accelerating clean energy solutions; $14,000 from South Florida-based Presidente/Tropical Supermarket; $13,000 from Associated Industries of Florida, a political committee representing employers across the state; $10,000 from Voice of Florida Business; and $10,000 from Coral Gables-based holding company JACRU.

Suarez’s spending went mostly to general fundraising and campaign costs. His biggest expenditure was $221,554, paid to Miami agency Artisan Media Group for advertising, outdoor media, political consulting, campaign email marketing, digital media, mailers, yard signs, TV ad production, website development, and social media and ad consulting.

Other expenses included $26,500 to Brickell-based fundraising consultancy firm BYD Strategies; $34,400 for mailers from Georgia-based company The Stoneridge Group; $10,000 to Miami agency Victory Campaign Strategies, also for mailers; nearly $9,000 to communication strategies firm JHSM Holdings; $5,200 to law firm Meyer and Bloom for legal fees; and $5,000 to Coral Gables-based Tridente Strategies.

The competition

Suarez’s best-performing opponent in the fundraising field is Martinez, a former college footballer who now produces Everything DB, a show hosted by former NFL defensive back Darius Butler.

Martinez’s filings with the city show he used to manage venture capital at Miami private equity firm General American Capital Partners.

His platform priorities include creating more affordable housing, broader and more accessible transportation, preventing crime and addressing Miami’s “environmental crisis,” including a “civilian climate corps.”

“We are facing time-sensitive issues that no other city has ever dealt with before and need to act with urgency,” he wrote on his campaign website. “To change the political culture of the City of Miami, it needs to be shocked. Miami-made and Cornell-educated, I plan on doing just that. I’m the 30-year-old fearless leader who believes everything is earned, not given.”

Over the course of his campaign, Martinez raised nearly $21,000. He had about $5,700 left as of Oct. 15, which is roughly as much as he pulled in over the preceding month and a half through 22 individual donations ranging from $9 to $1,000.

The $15,000 or so he spent since launching his campaign last November went mostly to general campaign activities, including web domain costs, ads, signage, flyers and email lookups.

The next-best fundraiser — with an asterisk — is Pichel, a former Miami police officer-turned-private investigator whom the Monroe County Sheriff’s Department arrested Oct. 1 on a felony charge of impersonating a police officer.

Former Miami Police Chief Art Acevedo named Pichel in a controversial memo to city officials late last month as someone under the employ of Joe Carollo, the notoriously combative Miami Commissioner who subsequently, and successfully, led calls for Acevedo’s termination.

Pichel entered the mayoral race late, registering in mid-September. His only campaign contribution was a $5,000 self-loan, of which $1,070 was spent on a city qualifying fee.

He’s spent nothing since.

Exantus, who is running on a platform to raise the hourly minimum wage to $25, fund vertical farming, decriminalize drugs, and end the stigmatization of sex workers and homelessness, among other things, has less than $300 on hand.

She reported having spent $352 on political flyers and for advertisement in the Miami New Times.

Then there’s Dutrow, who entered the race Feb. 10 and received his sole campaign contribution seven days later: a $150 check from retail worker Charles Guerra.

Dutrow still has the cash; he hasn’t reported spending a dime since.

A fifth candidate, Mayra Joli, was disqualified from the race last week. She had not resided in Miami for at least one year prior to the qualifying period.

The homestretch

A former Miami Commissioner, Suarez heads into Election Day about as close to a shoo-in as possible. When he won office in 2017, he earned 86% of the vote. Many believe he’ll have a similar showing this time.

Suarez appeals to voters on both sides of the aisle. He’s a pro-business, pro-police, regulation-reducing Republican and Miami’s first native-born Mayor. He also opposed former President Donald Trump, stood up to Gov. Ron DeSantis on COVID-19 safety measures — resulting in a still-unrepaired rift between the two men — and has made his cell phone number pubic, explaining: “I believe that our residents should always have a direct line of communication with me.”

But he isn’t entering the election unscathed. Acevedo’s public roasting at the hands of Carollo and others on the Miami Commission was a bad look for the young Mayor. Suarez and City Manager Art Noriega handpicked Acevedo to lead the police force, circumventing a traditional candidacy and vetting processes. Suarez famously called Acevedo “the Michael Jordan of police chiefs.” That Noriega was in the dark about many of Acevedo’s past misdeeds, and that Suarez was slow to respond to the issue but quick to deflect blame, may have been off-putting to voters who paid attention.

But as was the case in 2017, Suarez far outpaces his opponents in the key areas of experience and popularity. He’s also had many successes over the last two years, including attracting oodles of tech, investment and wealth management firms to his city, which he’s done a banner job of promoting as a Wall Street-Silicon Valley hybrid with more favorable tax laws and pleasant weather.

A lot of people in and around Miami know it, too. After all, he’s had — and spent — more than enough money to get the word out.