It was another disappointing calving season for North Atlantic right whales — only 15 calves born for a species that needs seasons of 50 or more to halt its slide into extinction. Some of the best and brightest in whale conservation in the Southeast met online this week to take stock and look to the next steps in trying to save one of the largest mammals in the world from dying off.

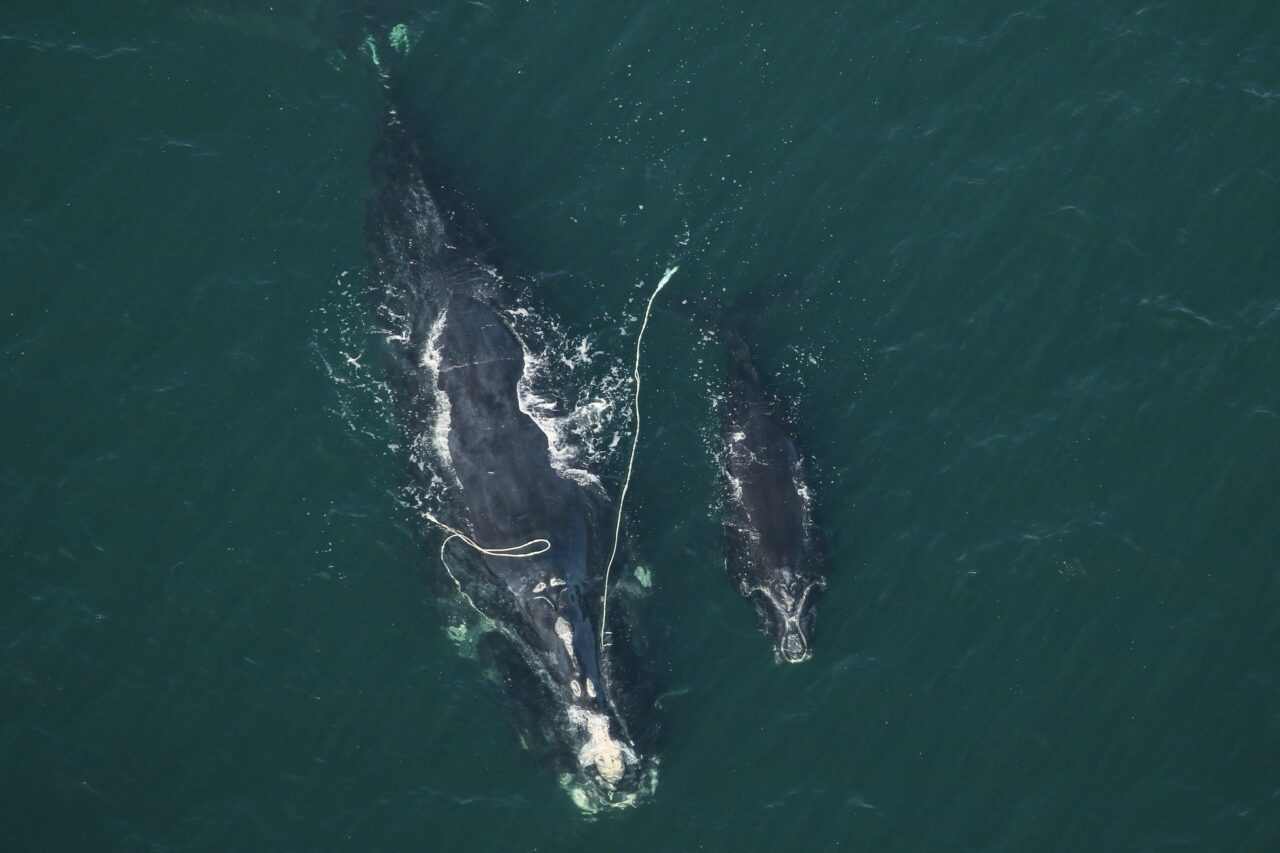

The news for Snow Cone, one of the most famous living right whales, isn’t good. Snow Cone generated no small amount of publicity this season in giving birth while entangled in potentially lethal heavy fishing rope.

“The big question in this case that persisted up until this season was whether or not this wound on her rostrum, which is the tip of her jaw or head there, whether or not that wound had rope embedded in it or not,” said Clay George, wildlife biologist for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Georgia DNR), at the meeting of the North Atlantic Right Whale Southeast Implementation Team (SEIT).

The SEIT is a federal and state interagency group that includes representatives from Georgia DNR, the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), along with other agencies and organizations.

In previous, similar cases, George said, Snow Cone’s sort of entanglement was deadly. An FWC sighting team in January got close enough to get a good look at the wound and photographs showed there was indeed rope embedded. Removing heavy fishing gear from a right whale is a potentially fatal endeavor for crew members involved in optimal circumstances — a mother with a new calf was not an optimal circumstance.

It’s also tough to cut an entanglement like Snow Cone’s, around the mouth, because she wasn’t going to open her mouth to feed until she left the calving grounds, much later and further north. Spotters saw her and her calf near Cape Cod in late April, where they provided clearer evidence of the embedded rope. Teams were unable to get a good opportunity to remove the rope the last time, and it’s believed she still has the rope in her wound around her mouth.

“Unfortunately, that means her future is very uncertain,” George said.

Meanwhile, warming oceans as an effect of climate change make life harder for the other calving females, fewer than 70 of which are believed to be alive. In all, scientists believe there are fewer than 340 total North Atlantic right whales remaining.

Calving intervals have grown in recent years. Before, a North Atlantic right whale might calve once every three to six years. For many calving females, that number has grown to double digits. One of the reasons is it’s harder for these females to pack on the blubber necessary to make the long trip south and back, along with nursing their calf. Warming oceans are forcing zooplankton north, and the right whales that feed on the small creatures follow, meaning it’s a longer swim back to Florida requiring more blubber.

This season, one whale gave birth for the first time in 13 years, but two made unusual quick turnarounds and gave birth two years after their last time. Removing both two-year mothers, the average calving interval moves from 7.7 to 8.5 years.

“Even though the moms this year are all reproductively active females, they’re still not giving birth as often as they’re capable of, on top of the fact the young females, they’re lagging in the recruitment of the breeding population,” said Melanie White, right whale conservation project manager for the Clearwater Marine Aquarium Institute.

As of Tuesday, spotters saw 10 of the 15 moms back in their northern feeding grounds. Spotters don’t expect to see one of the 15 calves from this season, which was born to Half Note.

“From the first sighting of this calf, the calf was emaciated and continued to show no sign of improvement in subsequent sightings,” White said. “Mom has since been seen in the Northeast, alone, so the calf is presumably dead, even though no carcass was ever detected.”

Half Note lost four of her previous calves in a similar manner.