The Florida State University official once in charge of the office that counsels campus rape victims told lawyers suing the school that football players receive special treatment, and that most of the 20 victims who alleged sexual assaults by team members during the past nine years declined to press student conduct charges.

Melissa Ashton, who had been director of FSU’s victim advocate program until August, made the statement in a deposition given this past June in an ongoing civil lawsuit filed by former student Erica Kinsman against the university. Kinsman says the university failed to respond to her allegations that she was sexually assaulted by ex-Seminoles quarterback Jameis Winston.

The Associated Press does not routinely identify people who say they are sexual assault victims. However, Kinsman told her story publicly in a documentary. She has also filed federal lawsuits against FSU and Winston.

Winston, who is now the starting quarterback for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, denied Kinsman’s allegation and was cleared of wrongdoing by FSU following a hearing late last year. A Florida prosecutor chose not to press criminal charges in late 2013, saying there were gaps in the accuser’s story and there wasn’t enough evidence to win a conviction.

Speaking of others who said they had been sexually assaulted at the school over the past nine years by football players, Ashton said the majority “chose not to go through a process, a lot of times based on fear.” Ashton said victims had “a fear of retaliation, seeing what has happened in other cases and not wanting that to be them.”

A spokeswoman for FSU said the university could not confirm or deny Ashton’s figures because her “communication with victims is confidential.” But Browning Brooks also said it may difficult to verify how many cases actually involve student athletes.

“Absent a student being willing to report outside of the confidential walls of the victim advocate program, the hands of the criminal justice system and the university’s conduct code proceedings are tied,” Brooks said in an email. “We cannot act on allegations of which we are unaware.”

In her deposition, Ashton estimated that her office had probably dealt with as many as 40 cases involving football players and other incidents of “intimate-partner violence.” She added that her office offered help to more than 100 victims of sexual battery on FSU’s campus during 2014. She was somewhat critical overall of how the university deals with student conduct cases, saying, for example, that the university does not have a practice of expelling students who violate student conduct rules.

But in her statements she said she was concerned that athletes get preferential treatment during investigations of misconduct, including access to an athletic department official who helps them get access to outside lawyers.

The university, in response to a public records request, released depositions of both Ashton and FSU Coach Jimbo Fisher late Wednesday. FSU had tried to get a federal judge to block the release of all deposition transcripts related to the case; in late October the judge refused.

FSU still wound up redacting large parts from both depositions, contending they are education records exempt from Florida’s public records law.

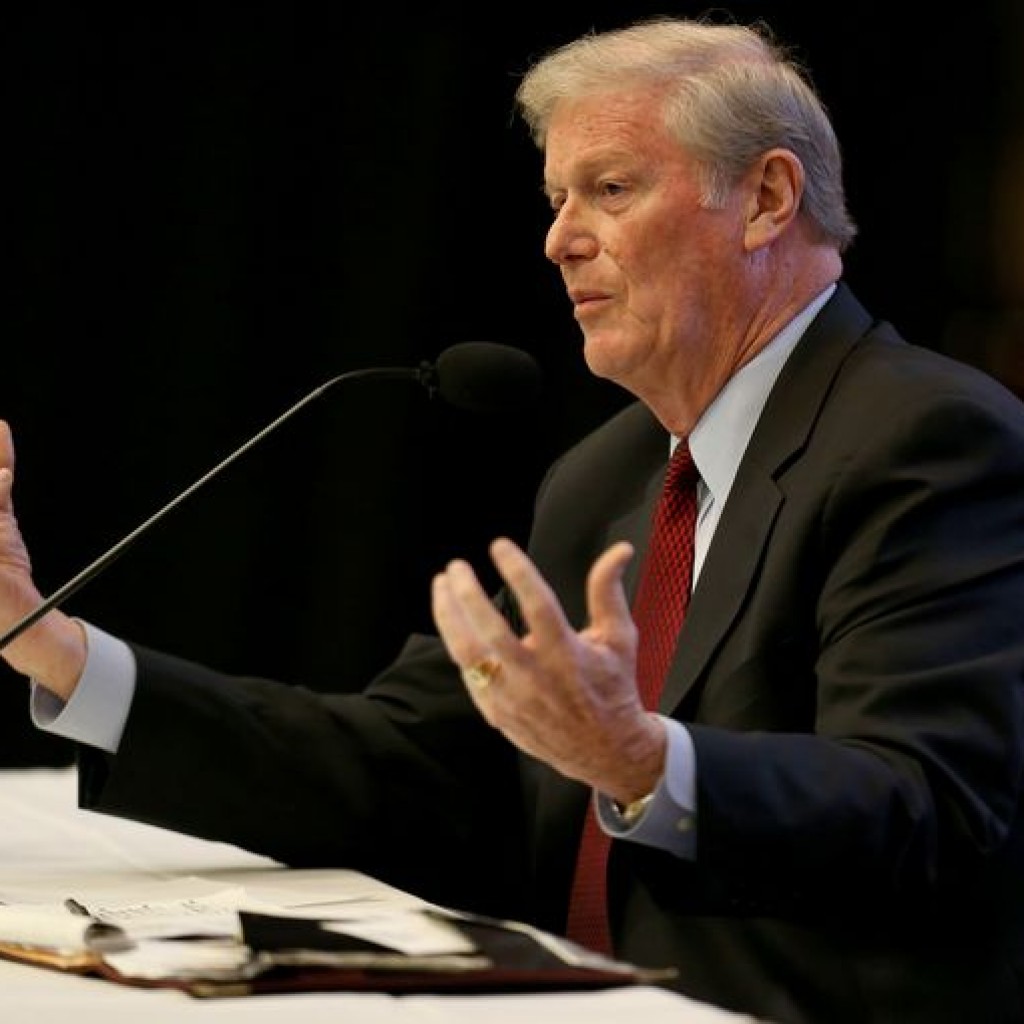

Fisher, for example, was questioned for roughly five-and-a-half hours in September. But the parts of his deposition that were released centered only on his knowledge of university policies regarding student conduct, including sexual assault. Fisher said that he did not know what the university policy was during 2012 and 2013 and said he would reported any incidents to his superiors not to police at the time.

Fisher did not make himself available to reporters following his weekly radio show.

FSU President John Thrasher recently objected to a documentary on CNN regarding sexual assault on college campuses that focused on the Winston case. He released a statement saying FSU “does not tolerate rape” and that the university has made changes to its policies regarding sexual assault complaints.