Donald Trump‘s effort to unite a splintered Republican Party around his candidacy is about to take center stage in a city that is itself deeply fractured.

Once an industrial powerhouse, Cleveland is one of the poorest and most segregated big cities in America. Two out of five people live below the poverty line, second only to Detroit. Infant mortality rates in its bleakest neighborhoods are worse than in some Third World countries.

The city’s mostly blighted east side is almost entirely black, the slightly more prosperous west side more mixed. And there’s deep distrust between the black community and police, in part because of police shootings such as the killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice and a U.S. Justice Department report that found a pattern of excessive force and civil rights violations by the department.

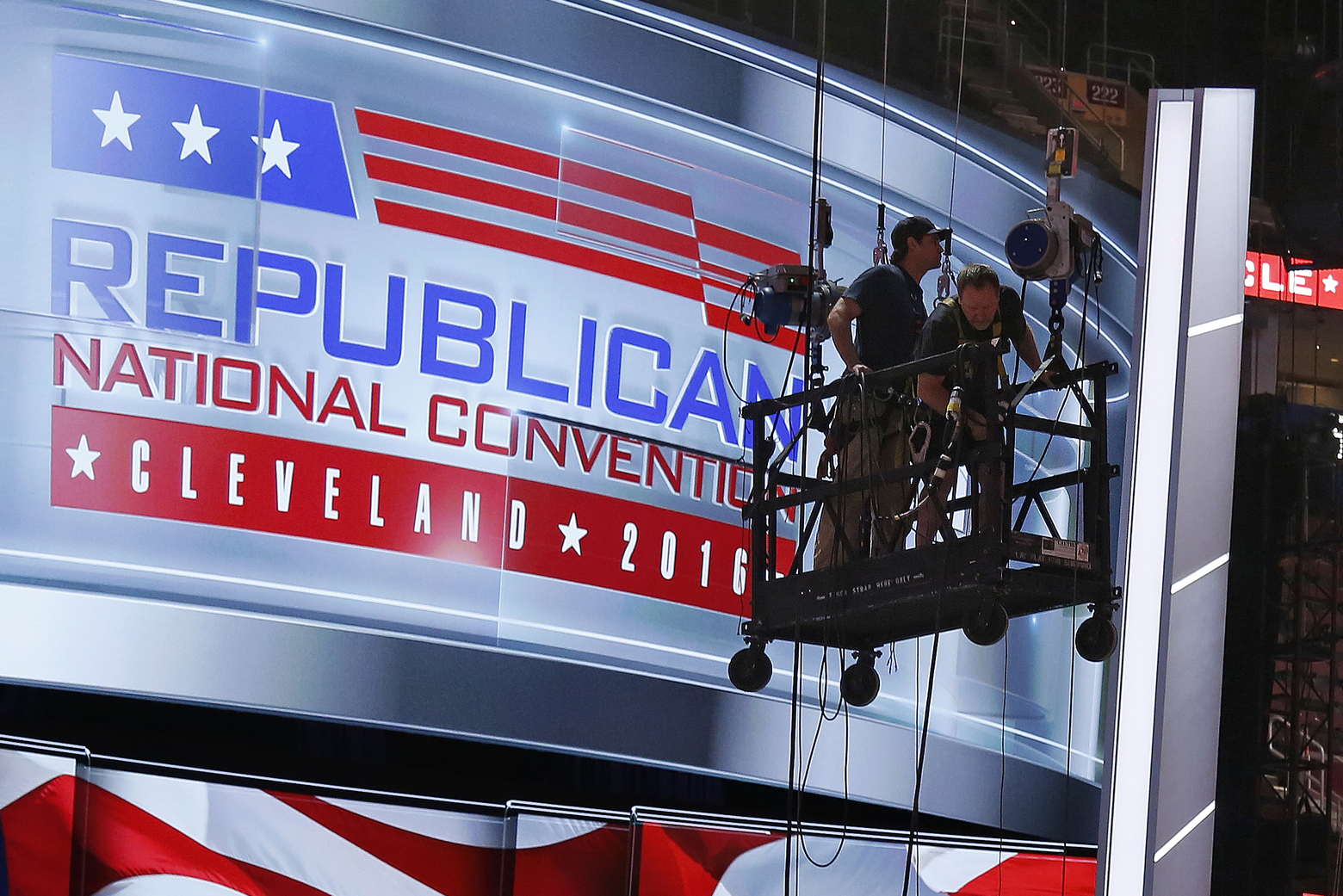

Yet there are also islands of prosperity, created in part by a wave of college-educated young people moving into downtown neighborhoods, a trend that has reshaped the city’s image and helped attract the Republican National Convention, which will be held July 18-21.

“It’s a city full of neighborhoods and a city full of divides,” said John Grabowski, a local historian.

___

This is the place that in the 1970s — when the city was in default and a quarter of its population was moving out — embraced the slogan “Cleveland: You Gotta Be Tough.”

Tough is a good way to describe Cleveland’s east side, where blacks from the South filled industrial jobs and settled during and after World War II. It’s now marked by high crime and abandoned factories. Over half the children live in poverty.

Chris Brown, a 41-year-old black man and lifelong Clevelander, admits he was part of the problem in his younger days. “I was a thug, almost. On a highway going nowhere fast,” he said.

Caught selling drugs, he went to prison for three years. Afterward, getting by was a struggle until he started working at a commercial laundry four years ago.

Funded by civic leaders, foundations and local institutions, the laundry is part of a wider mission to stabilize east side neighborhoods by creating jobs. Built inside a former torpedo factory, it employs about 40 people, most of whom have done time in prison, and operates as a worker-owned cooperative. The employees can use their wages to buy a piece of the company and get a split of the profits.

Brown took advantage of its loan program to buy his first house on the east side, where 1 in 5 homes is vacant. “Where we come from, there ain’t many guys like that,” Brown said.

Those behind the cooperative, which also operates a greenhouse and a renewable-energy business, aren’t selling it as a solution to pervasive unemployment. But it’s a bright spot in an area desperately needing something positive, said plant manager Claudia Oates. “It shows we work, we believe in work,” she said.

The convention will mean more hotel sheets for the laundry to wash, but apart from that, Brown said, the money the event will bring into the city won’t show up where he lives.

“I don’t know many black people who’ve got anything to do with convention,” he said. “Nobody else I know is getting a job or money from the convention.”

___

Downtown is where delegates will spend their money at souvenir shops and sidewalk cafes.

It’s also where millennials are moving into renovated warehouse apartments and new condominiums. Once a ghost town at night, it’s now home to 14,000 people.

In the two years since the GOP awarded the convention, vacant downtown storefronts have been filled with new businesses, and the Public Square underwent a $50 million renovation. Health care and high-tech jobs are drawing young people, stabilizing the city’s population at about 388,000 after a peak of over 900,000 in the 1950s.

“Cleveland’s got a long way to go. I’m not going to sugarcoat it,” said Bill Mangano, a white man who bought a downtown apartment after growing up in the city’s western suburbs. “We’re never going to be New York or Chicago, but we can carve out our own place.”

Peter Karman, a 27-year-old white man, left behind a two-hour commute in San Diego for a job within walking distance.

“All of my family and friends asked, why Cleveland?” he said. Here, he said, he can afford a lifestyle not possible in California, living in a downtown warehouse overlooking the Cuyahoga River.

___

The crooked river that caught fire during the 1950s and ’60s from industrial pollution sparked an environmental movement resulting in the federal Clean Water Act. But in Cleveland it was the city’s racial boundary for many generations.

Blacks stayed east of the river and out of the white neighborhoods to the west, fearing unwelcome stares and police harassment.

Kevin Conwell, a black city councilman, remembers his parents warning him 40 years ago not to cross certain streets or risk having the police haul him back home.

“People my age still tell kids not to go over there,” he said. “How do you break down that gap?”

To this day, many of the east side neighborhoods are at least 90 percent black, according to census data. But over the past 15 years, more blacks are moving to areas once off-limits, creating neighborhoods that are more racially diverse yet still poor.

Overall, blacks make up about 53 percent of the city’s residents, whites 37 percent, Hispanics 10 percent.

What’s holding back the neighborhoods now, Conwell said, are companies and unions that won’t hire minorities and lenders that won’t offer them home loans.

“When you’re not working, you tear your neighborhood apart,” he said. “That’s your great divide.”

Republished with permission of the Associated Press.