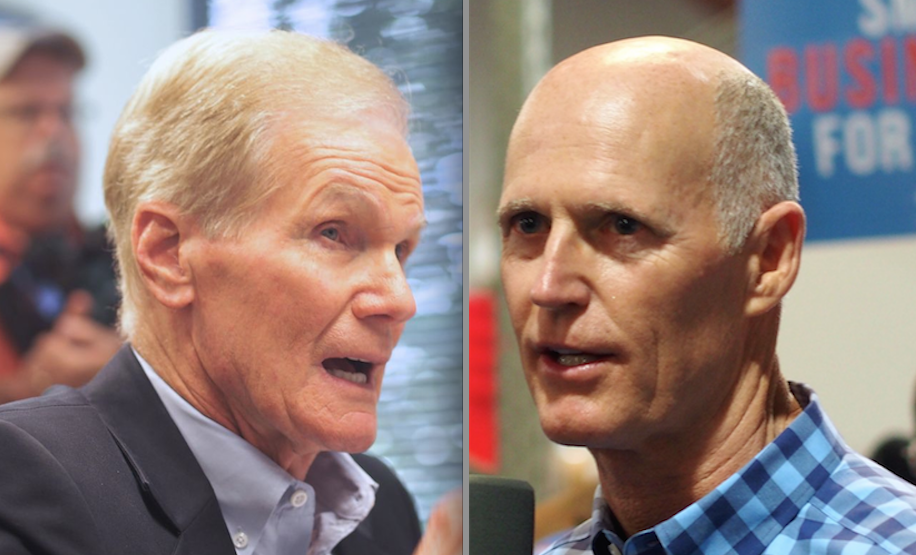

Despite GOP Gov. Rick Scott claiming victory Tuesday night, the U.S. Senate election between him and incumbent Democrat Bill Nelson is heading to a recount.

The initial margin of victory is less than a half-percent, which triggers an automatic machine recount under state law. Just 26,056 votes separate the two candidates out of more than eight million cast, according to the state’s elections website.

Scott, a former Naples businessman, won election as governor in 2010 by one percent, and then won re-election in 2014 by one percent, and looked to have knocked off Nelson by less than one percent.

At 12:15 a.m., Nelson’s longtime chief of staff, campaign manager and confidant Pete Mitchell addressed what was left of his campaign party, declaring the race had been called by multiple media outlets, that Scott had won, and that Nelson would be making a statement Wednesday.

“Numerous reports on the Senate race have called it for Gov. Scott. This is obviously not the result Sen. Nelson’s campaign has worked so hard for. The Senator will be making a full statement tomorrow.” An exhausted-looking Mitchell then left the room.

In the light of day Wednesday, a new reality emerged: those South Florida votes came in and put the race in recount territory.

“We are proceeding to a recount,” Sen. Nelson said Wednesday morning in a brief statement.

From here, local supervisors of election will recheck the tally, and the Nelson campaign will contact voters with verification issues. The campaign will have observers in all 67 counties.

As a measure of how close Tuesday night was, this isn’t even the biggest statewide nail biter: a manual recount scenario is in play for the Agriculture Commissioner race between Democrat Nikki Fried and Republican Matt Caldwell, with the margin there at 8,254 votes and outstanding mail ballots from Democratic strongholds Broward and Palm Beach, as well as Democratic performing Duval County.

The Governor’s race between Democrat Andrew Gillum and Republican Ron DeSantis, meanwhile, is also on a razor’s edge, though with a 0.58 percent spread it is outside of recount territory. If Gillum snags another 6,000 or so votes, he and DeSantis will join the club.

A close call after an expensive election on both sides.

A Scott spokesman criticized Nelson immediately: “This race is over,” Chris Hartline said. “It’s a sad way for Bill Nelson to end his career. He is desperately trying to hold on to something that no longer exists.”

This election not only shattered Florida records for money spent on the campaigns — $177 million through last week, with bills still not posted — but also set new low-water marks for negative campaigning, as both candidates and their allies strove to define or redefine their opponents:

— For Scott, that meant Nelson and several Democratic committees combined to spend at least $80 million convincing voters that the governor cut education funding, stripped away environmental protections, oversaw Florida’s red tide disaster, waffled on health care pre-existing conditions coverage, refused to expand Medicaid in Florida, pushed through tax cuts that made rich people richer, and had a dodgy business career, highlighted by massive Medicare and Medicaid fraud by his company.

— For Nelson, that meant Scott and the New Republican PAC spent nearly $100 million, including at least $51 million of Scott’s own fortune, convincing voters that Nelson’s accomplished little or nothing in a half-century in public service, other than voting along Democratic lines in key moments involving taxes and health care; has long been an empty suit collecting government pay and amassing government pension benefits; and that he’s getting old, and perhaps growing “confused.”

Campaigns are “divisive” and “tough,” Scott said.

“And they’re really actually way too nasty,” he said. “But you know what? We’ve done this for over 200 years, and after these campaigns, we come together.”

That kumbaya moment won’t happen until after the recount, however.

While Scott’s campaign aggressively and sometimes angrily fought back against the charges leveled against him in the Democrats’ campaigns, Nelson mostly shrugged off Scott’s attacks.

The governor, in what may have been a premature victory speech, vowed to bring to Washington the same business-like approach he used as an outsider when he assumed office eight years ago as governor.

“The federal government is frustrating. It’s outdated. It’s wasteful. It’s inefficient,” Scott said. “All of us in state government have dealt with the federal government over the last eight years, and we can tell you story after story after story. Now, I’m just one individual, but there are a lot of other individuals in D.C. that want to do the same thing. And I’m going to work with them and we will change, like we did in Florida, the direction of Washington, D.C.”

For all his public awkwardness that supporters say makes him look genuine and critics say makes him look creepy, Scott managed, especially in the closing weeks, to project a sincerity: someone who looked in command overseeing hurricane recovery, someone who looked comfortable playing with his grandchildren, someone who sounded true stating his positions.

Also in play was Nelson’s card-carrying membership in the opposition to President Donald Trump, while Scott went from close friend and ally of Trump, to someone who hardly ever spoke the president’s name, to someone who joined the divisive party leader at a rally last week. In huge swathes of Florida outside the urban cores, Trump’s support may remain unchanged, and party leaders like Volusia Chair Tony Ledbetter spoke of a Republican base that was angry, ready to vote.

Many political observers postulated that Nelson had never previously been seriously challenged in his Senate campaigns, beating then-U.S. Rep. Bill McCullum in 2000; controversial Secretary of State Katherine Harris in 2006; and then U.S. Rep. Connie Mack IV in 2012, each by easy margins. Lucky some called him.

Scott, meanwhile, was seen by many political observers as someone capable of overcoming negative campaigning against him to come out of nowhere to win, as he did in 2010, defeating Alex Sink 49-48; or with an underwater favorability rating, as he did in 2014, defeating ex-Gov. Charlie Crist, 48-47. His personal wealth certainly helped: he spent $73 million of his own money in 2010, and at least $51 million this time.

However, the election isn’t over. Yet.

__

Orlando correspondent Scott Powers, Jacksonville correspondent A.G. Gancarski, and The News Service of Florida contributed to this post.