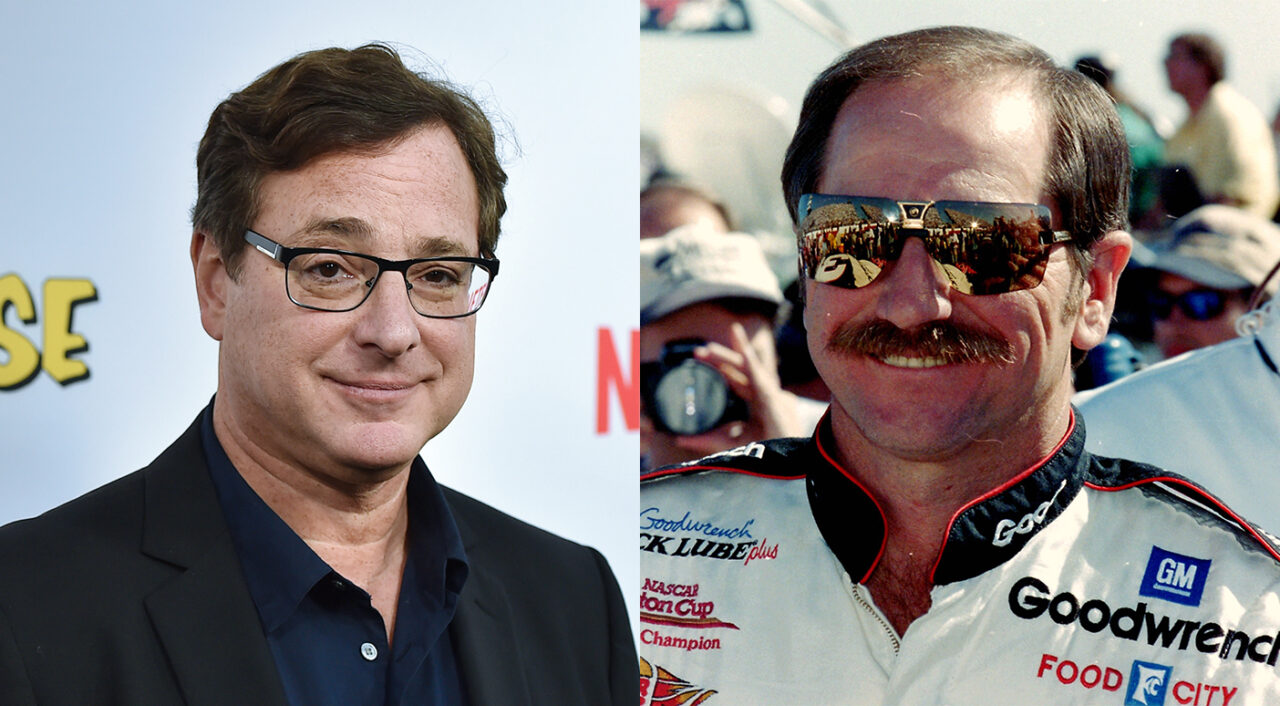

When the family of the late comedian Bob Saget sued Orange County officials last week to prevent public release of autopsy and death scene photos, the action echoed a similar high-profile case and lawmaking from 21 years ago.

After NASCAR driver Dale Earnhardt Sr. died in the 2001 Daytona 500, Florida’s famously-broad open records laws were tested — and changed — in a prolonged, high-profile, bitter battle involving various news outlets, Earnhardt’s family, Gov. Jeb Bush and Senate President Jim King.

Now, that law — dubbed the Earnhardt exemption — could be tested in one of the highest-profile cases since.

“I read some national media referred to it as an ‘arcane law.’ If it is arcane, it’s because it hasn’t had to be used regularly. But I think it shows the validity and the strength of the law, that when it was needed, it was there,” said Gus Corbella, Senior Director of Government Law and Policy at Greenberg Traurig. In 2001, he was Staff Director of Senate President King’s office, and helped craft the law.

“Florida public records laws are one of the cornerstones of our state,” Corbella said. “At the same time, though, I don’t think public records laws ever envisioned a loved one’s autopsy pictures being made public.”

The 2001 law that the Legislature passed and Bush quickly signed said that autopsy photographs, videos, recordings and other materials, and crime scene photographs and videos of a death, are confidential, not to be released as public records. There is a caveat: If a judge hears a challenge, and deems that greater public good would be served by their release, the material can be made public. And the judge can limit that release to as few as one person.

On Feb. 15, Saget’s widow, Kelly Rizzo, and adult children, Aubrey Saget, Laura Saget and Jennifer Saget, sued the Medical Examiner’s Office of Florida’s 9th Judicial Circuit and Orange County Sheriff John Mina. Saget’s family members sought to get the court to declare that Saget’s autopsy and crime scene images and recordings should not be released.

Circuit Judge Vincent Chiu in Orange County quickly granted a temporary injunction preventing the release of any photographs, video recordings, audio recordings, statutorily protected autopsy information and all other statutorily protected information related to Saget’s death.

That opens the prospect for a court battle over those records, though to date no one has filed to challenge the family.

As of Monday, the Medical Examiner’s Office in Orlando had received Saget-related public records requests from at least 113 people — mostly, but not all, from journalists.

Most of those requests, however, were simple and requested fairly routine information. Only two explicitly asked for autopsy and crime scene photographs, recordings and other materials, though a few others made requests along the lines of “any and all” materials released, which probably would cover photographs.

At issue may be clarification of what happened when Saget unexpectedly died Jan. 9 at the Ritz-Carlton Orlando, Grande Lakes resort. Short statements from the Sheriff’s Office and Medical Examiner’s Office said only no foul play or drugs were involved, and a preliminary autopsy suggested brain bleed, perhaps from a tragic slip-and-fall incident.

By mid-February, however, outside medical experts were suggesting far more traumatic head injuries than might be expected from a slip and fall. Those reports led to a flurry of media requests, and, presumably, to the family’s legal action to shield the photographs.

There have been other uses of the Earnhardt exemption. In 2010, when SeaWorld animal trainer Dawn Therese Brancheau was attacked and killed by an orca, her family invoked the law to prevent release of videos of the attack. In Dixie County, the law was used to prevent release of any pictures of two young children who were murdered by their father before he killed himself last year.

The fear of wanton exploitation of grisly death photos and videos of a celebrity was just as real in 2001, even at that stage of the internet. Earnhardt’s widow, Teresa Earnhardt, vigorously fought against their release. Bush and King pushed hard for quick approval of a new law.

“It was like ‘full-speed ahead’ to try to get that done because there were these websites that were trying to obtain these autopsy photos. It wasn’t even like your general gossip rags. It was literally web pages that existed solely devoted to including autopsy pictures, murder-scene pictures, horrific things,” Corbella recalled.

Rod Smith had been State Attorney in Gainesville in the 1990s. He had battled against media requests for victims’ crime scene photos from the Danny Rolling “Gainesville Ripper” mass murder case, eventually negotiating a truce.

“I was never going to release those photos. I was never going to let that happen,” Smith said.

He remained frustrated that the law could allow the photos’ release.

“It was unclear. But the law leaned towards that you lose your right of privacy in death,” Smith recalled. “In other words, you can’t claim a right to privacy; you’re dead.”

In 2001, as a Democratic state Senator, Smith was recruited to help write the Earnhardt exemption law, and to help King push it through.

Yet there also was a compelling public interest in Earnhardt autopsy photos, pursued in court by the Orlando Sentinel and the The Alligator student newspaper at the University of Florida.

In the week before the 2001 Daytona 500, the Sentinel had published an investigative series of stories about safety issues in NASCAR racing, with headlines like “NASCAR IDLES WHILE DRIVERS DIE.” One of the prime subjects of the investigation was NASCAR’s refusal to mandate use of the HANS device, a restraint system for drivers’ heads and necks seen by many as paramount to preventing fatal injuries in front-end crashes.

Earnhardt was personally opposed to HANS devices and didn’t wear one himself. More than that, as the sport’s biggest star, he was identified as the ringleader of NASCAR’s opposition.

When he shockingly died in a front-end crash three days after the Sentinel’s series concluded, the paper wanted to know: Would a HANS device have saved his life? Might detailed autopsy photographs and records prove this? The paper went to court to get them, opposed by Mrs. Earnhardt and others, who contended that if the photos were released to anyone, they’d surely would wind up going viral.

“We filed a (records) request, not so we could publish, but so a doctor could go in and take a look at the records and write a medical opinion about how Earnhardt died,” recalled Tim Franklin, who was then executive editor of the Sentinel. Franklin now is Senior Associate Dean and the John M. Mutz chair in local news at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in Chicago.

What started as a viciously hostile dispute eventually got worked out — and got worked into the new law. The Earnhardt exemption provides that in situations of compelling public interest, someone — the Sentinel in the case of that moment — could go before a judge to argue that someone needed to see the autopsy materials.

“We left the door open for examination,” Smith said. “It’s just that we weren’t going to make it carte blanche.

The Sentinel argued that the issue of safety for all drivers in the entire sport was at stake. The judge allowed a nationally-renowned neurosurgery professor from Duke University to examine the autopsy materials, alone, in the judge’s chambers. The doctor concluded that a HANS device might have saved Earnhardt.

Within a year, NASCAR approved sweeping new safety requirements, including mandating that all drivers wear HANS devices.

Franklin pointed out there has not been a fatality at a NASCAR Cup Series race since.

Smith said that the Earnhardt exemption worked as envisioned in that first case, and appears to be an ideal route in the Saget case.

“The law is to protect against wholesale release of photographs without good reason,” Smith said. “It did not eliminate the ability of the public to find information in specific instances.”

In the first month after Saget’s death, little information was revealed, except that foul play and drugs were ruled out. On Feb. 9, TMZ, citing unnamed sources, broke news that Saget died of a brain bleed caused by a head injury. On Feb. 11, Medical Examiner Joshua Stephany released a preliminary autopsy report confirming that, with some detail.

Media found outside experts who surmised the detail showed far more injury than might have occurred from a simple fall.

“It appears, at least as reported, that the blow was disproportionate from what you would have expected from just falling and bumping your head,” observed Smith, who cautioned he has not looked into the case and is not involved.

Corbella said the law was written for situations like Saget’s death.

“That’s the reason it was created, to protect the dignity of the deceased, and to protect the family who is suffering. The last things they should be worried about is whether their loved ones’ private information or photographs could be shot around the world with a click of a button,” he said.

“I know that Jim King would be smiling down from heaven, knowing the work that he did is still making a difference decades later,” Corbella said.