The exclusive private mansion long stood as a goal for many a homeowner. But planning consultant Victor Dover suggests isolation doesn’t make for a happy or long life — nor does crafting policy around a desire for isolation lead to smart politics.

The principal-in-charge for famed South Florida planning firm Dover, Kohl & Partners closed out SWFL Inc.’s State of the Region event. As affordable and attainable housing dominated much of the conversation during the day, Dover said everyone from elected officials to development professionals needs to take a fresh look at their practices and expectations.

Among other things, he noted that Florida’s long history of sprawling subdivisions carefully crafted to limit contact with neighbors isn’t helpful in creating a sense of community or to encourage residents to embrace further growth or change.

“If you sell community, every time you add something, it adds to what you sell,” Dover said. “Sell isolation, thinking you are going to get away with it for awhile, and it’s why people in Phase I turn out to oppose Phase IV.”

He encouraged those crafting land use and planning neighborhoods and communities to always remember the value of public community spaces. Examples exist throughout the country where what draws consumers and citizens to projects is the shared space around them, especially those aiming to make density into something more palatable.

He pointed to a development known as Newpoint on the waterfront in Beaufort, South Carolina. The project earned a write-up in the Wall Street Journal for a simple decision regarding the greatest commercial asset for the plan. Rather than carve up the real estate to sell as premium units, planners flipped the homes around to face the waterfront and put a sidewalk-accessible public amenity so even those living blocks away could enjoy the shore. The homes adjacent still could enjoy a view. From the park, front-facing architecture made for a more pleasing environment. Even from the water, boaters could suddenly look at the most attractive features of homes rather than backyards and barbecue grills.

“The whole public realm improved,” he said.

In a world of dying malls, Dover also suggested there may be answers to be found on the affordable housing front by way of abandoned auto centers. He showed one of his firm’s projects where a vacant Sears building was rebuilt as a neighborhood with townhomes and park accesses.

Commercial development patterns created too many structures “that had a very short usable life,” Dover said.

“We have to get creative about how to create a place, physical place that the customers will feel more loyalty to,” he said.

The message resonated with many elected officials in the room, who hear frequently about struggles for citizens to find attainable housing, yet see many derelict structures in their communities.

“I would encourage our local elected officials to look into it and maybe get some planning ideas of how we can take some of these large retail areas, whether it’s a Kmart or a Sears, and have some of these live-work spaces,” said Rep. Lauren Melo, a Naples Republican.

Dover said the private sector must embrace change, but so must politicians. He quoted longtime Charleston Mayor Joe Riley, who said, “Your elected officials are the chief urban designers of your cities.”

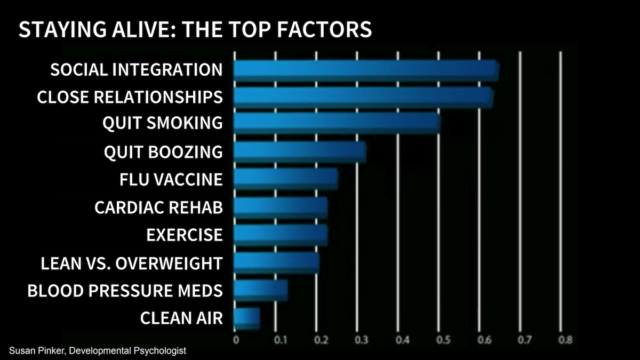

Finding ways to bring people together in more dense environments that encourage community interaction may also be good for public health, he said. He pointed to a study by psychologist Susan Pinker on factors that increase longevity. It found noticeable benefits for actions like quitting smoking or losing weight, but found social integration played a greater role than any other factor in the study.

“You’ll live longer then because every other aspect of your daily life is set up to make you more likely to promote physical health,” Dover said.