- Community Mediation Maryland

- criminal justice reform

- DOJ

- elderly prisoners

- EMPLOY

- Florida Department of Corrections

- Florida Policy Project

- Jeff Brandes

- Older prisoners

- Osborne Elderly Reentry Initiative

- Prison

- Prison reentry

- recidivism

- Senior Ex-Offender Program

- Thomas Baker

- U.S. Department of Justice

- U.S. Sentencing Commission

- University of Central Florida

- Washington State Institute for Public Policy

Florida has a recidivism problem.

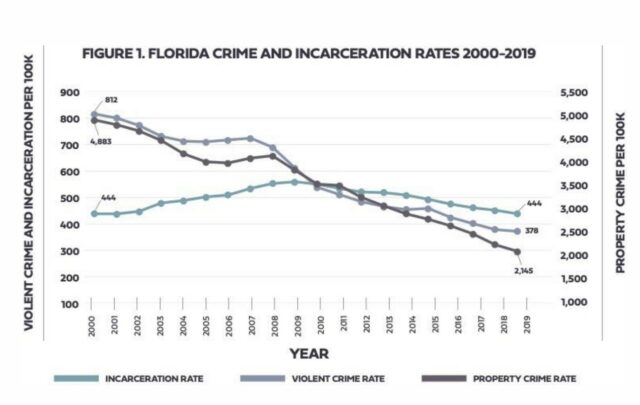

Despite a drop in crime of more than 50% between 2000 and 2019, the state’s incarceration rate has remained stable.

That’s because more than 60% of people released from prison in the Sunshine State will be arrested again within three years, a 2022 Florida Department of Corrections (DOC) report found.

While reducing crime is a prime purpose of incarceration, preventing future wrongdoing that adds to the 80,000-plus prisoners behind bars in Florida today should be a major goal as well, according to the nonprofit Florida Policy Project.

A self-described “policy bank,” the Florida Policy Project just released a pair of new reports, viewable below, examining Florida’s somewhat cyclical criminal justice system and how to cut down on adverse health effects most aging prisoners endure.

The first, titled “Best Practices to Limit Inmate Reentry to Florida’s Prisons,” suggests that to significantly shrink the state’s prison reentry rate, Florida must retool how it equips ex-inmates to succeed once they return to society.

“Florida has an opportunity to do more to keep our communities safe by educating and employing released inmates,” said Florida Policy Project President Jeff Brandes, a former state Senator.

“The data shows that states with robust education and job-focused reentry programs have better outcomes, which improves public safety. By offering improved education options, job training, and in many cases supervised release, Florida can improve its recidivism and improve outcomes.”

Budget cuts, understaffing and limited prison programming have worked counter to those objectives, wrote the report’s author, Dr. Thomas Baker of the University of Central Florida.

Just 17% of Florida prisoners who need help with substance use disorders have access to treatment. Sixty-four percent need general education services, but only 4% are enrolled. Prisoners who don’t receive the programming they need pose, Baker wrote, pose the highest risk of recidivism.

The report includes six recommendations to break the pattern. They include:

— Expanding work training and job skill development opportunities in prisons and other correctional facilities.

— Adequately funding general education and higher education services.

— Developing evidence-based programs that promote positive relationships between inmates and their loved ones.

— Expanding substance abuse and mental health treatment programs.

— Providing transitional services that continue to address needs from prison into the community.

— Funding and facilitating scientific evaluation of all state-funded programs to fine-tune each for better outcomes.

The report examines several existing programs from which DOC could borrow. There’s EMPLOY, a voluntary program in Minnesota through which inmates can gain work experience, job skills and improve their chances of employment with resume-writing, interviewing and job-application lessons. The program also uses “retention specialists” who meet with participants regularly to assist with their employment.

The results: Participants were 32% less likely to be reconvicted than their nonparticipant peers, 35% less likely to be arrested again, 55% less likely to be incarcerated again and 72% likelier to be employed within a year of their release.

It’s budgetarily sound, too. For every $1 spent, taxpayers see a nearly $17 benefit, according to a Washington State Institute for Public Policy analysis of the program.

Another program Baker examined is Community Mediation Maryland, which provides mediated visitation for prisoners in their final six to 12 months of incarceration. Participants can choose to meet with anyone on the outside who they believe will be important in their reentry to society.

A 2014 study found participants were 13% less likely to be rearrested, 15% less likely to be reconvicted for a new offense and 12% less likely to return to prison.

The report, viewable in its entirety below, is one of three papers detailing potential solutions to Florida’s corrections-related policies. The second is titled “Better Outcomes to Care for Florida’s Aging Inmates.”

A third report due in November will center on best practices for incarcerated veterans.

The elder inmate-focused report, also viewable below, offers several takeaways. Among them:

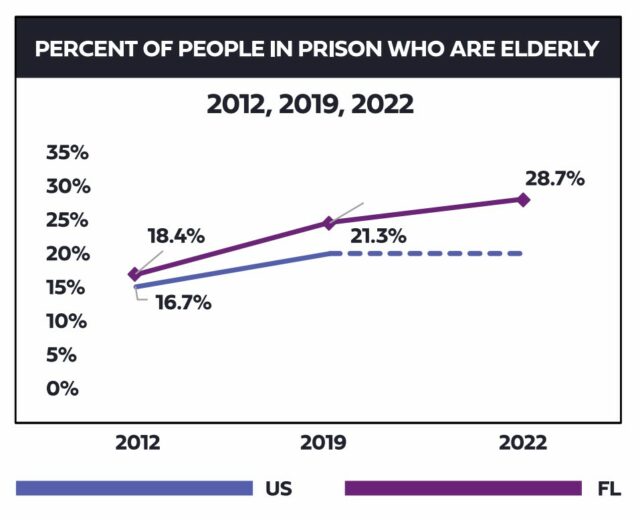

— About 29% of Florida’s inmates are 50 and older, a rate notably higher than the national rate, and it costs roughly twice as much to care for them as their younger counterparts. Prisons with the highest percentages of aging inmates spend five times more on average per inmate in medical care and 14 times more on prescription drugs than institutions with the lowest percentage, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

— Prison conditions contribute to adverse health effects that are worse among elderly inmates who, coupled with previously poor health care, drug use and nutrition, experience accelerated aging. Research suggests the average 59-year-old inmate presents geriatric conditions similar to non-inmates 75 or older.

— Older inmates are “significantly less likely” to reoffend, according to a July 2022 U.S. Sentencing Commission study, which found older offenders’ recidivism rates sat at 21% compared to 53% for those under 50.

To improve outcomes for Florida’s older inmates, Baker recommended that Florida introduce programs to ease reentry emphasizing their specific needs.

Take digital literacy. One program in Alabama that Baker cited provided eight weeks of training on computer basics, social media use and how to access health care services on the web.

It boasted a recidivism rate of 2%.

Transitional services like the Osborne Elderly Reentry Initiative in New York assists older ex-convicts with Medicare and Medicaid applications, Social Security and housing. Another in California called the Senior Ex-Offender Program offers similar services.

“Implementing some of the strategies employed by these nonprofits would be beneficial for the state’s approach to transitional services for elderly people leaving Florida’s prisons,” Baker wrote.

The last recommendation is geriatric release, which as its name suggests involves letting older inmates out of prison before their sentences would otherwise allow. Baker called it “perhaps one of the most efficient ways to reduce correctional costs.”

Florida today incarcerates more than 8,600 people 60 or older. And like every state except Iowa, it has a senior prisoner-specific policy in place now, though it’s only for prisoners “permanently incapacitated” or “terminally ill.”

“Not all of these people would be eligible based on time served or offense seriousness, but many would immediately meet eligibility requirements for release consideration if similar legislation were passed in Florida,” Baker wrote “Releasing even a fraction of the people over 60 could result in millions of dollars in savings for Florida taxpayers with the least risk to public safety.”

One comment

charger John

October 18, 2023 at 8:16 am

Prison is a big business in Florida. When viewed from that lens the picture is clear!

Comments are closed.