Bryan Paz-Hernandez is sick of traffic. He’s fed up with rising costs of living. And don’t get him started on public corruption.

He’s running for the Miami-Dade County Commission to, as the saying goes, be the change he hopes to see in the world.

“There’s a tendency for politicians to promise you the world and then, when they get into office, they don’t deliver,” he said. “I plan to deliver.”

It’s Paz-Hernandez’s first time as a candidate. And he’s aiming high.

His No. 1 goal, he said, is to reduce roadway congestion in the county’s Kendall area. The fix he’s proposing: a new transit line that’s either a Metrorail extension or light rail.

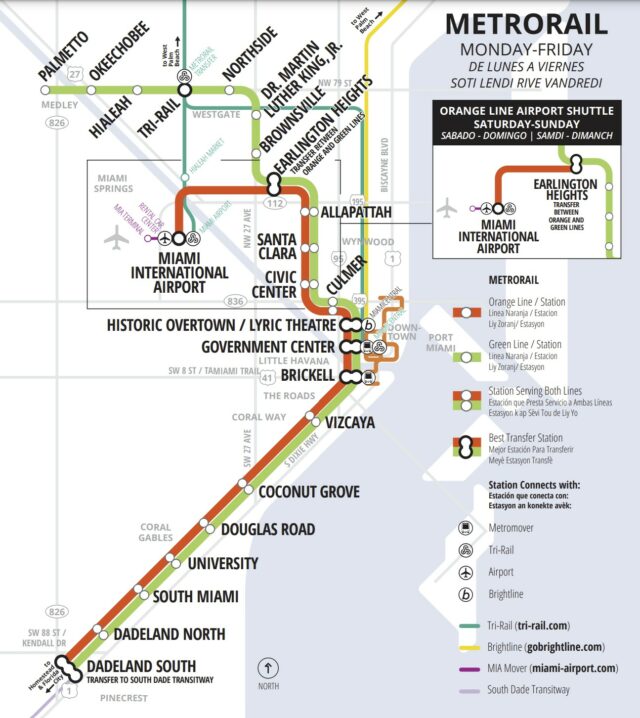

Paz-Hernandez wants to build elevated or ground-level rail beginning at the Dadeland South Metrorail Station on U.S. 1. The line would run west on Kendall Drive until Southwest 137th Avenue, where it would turn northbound before turning south again to stop at Florida International University’s main campus on Tamiami Trail.

From there, the train would reconnect to the nearby Palmetto Metrorail Station, creating a loop on the railway.

If it’s Metrorail, it would be the first addition to the 40-year-old system since the county opened the 2.4-mile Orange Line to Miami International Airport in 2012. It would also be incredibly expensive and displace many residents and businesses.

A 2019 Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) study of building an elevated Metrorail link from the Dadeland North Station to near Krome Avenue found that while it would attract the most riders while not taking away car lanes, it would cost $2.1 billion to build and $25.2 million for yearly operations and maintenance.

That Metrorail route was projected to run for 11 miles, take about 12 years to build and require 42 residential and 21 business relocations. FDOT recommended enhanced bus service instead.

Paz-Hernandez’s proposed solution would travel approximately 15 miles. The county could cover much of the construction costs and buy the land necessary for building it, he said, with federal infrastructure grants.

“I’m fully aware that what I’m talking about is not going to happen overnight, but we have to begin the conversation, and this campaign is part of that and hopefully making this a reality,” he said. “As a Commissioner, I will micromanage the hell out of this project. I’ll make it my brainchild, and if it does get approved — the money’s there — I will be on top of all the related agencies and contractors to make sure this happens as soon as possible.”

A high school teacher, Paz-Hernandez isn’t yet 30 but boasts life experience applicable to the work he hopes to do at County Hall. He was born and raised in the Kendall area to parents of Colombian and Honduran descent. He earned his bachelor’s degree in political science from American University in Washington.

He was a social worker with United Way Miami and a community engagement organizer for Catalyst Miami, a local nonprofit founded by Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava to help low-income county residents.

He also worked as a field organizer for former U.S. Rep. Donna Shalala’s successful 2018 campaign, a Campaign Manager for Heath Rassner’s campaign for the Florida House the same year and a strategist for Florida Rising and Progress Florida.

For a time, Paz-Hernandez served as President of the West Kendall Democrats Club. He switched to having no party affiliation last year.

He’s one of three candidates seeking the Miami-Dade Commission’s District 11 seat, which covers a swath of unincorporated neighborhoods on the county’s west side, including Country Walk, Hammocks, Kendale Lakes, Kendall, Bent Tree, Lake of the Meadows and West Kendall.

Standing in his way are incumbent Commissioner Rob Gonzalez, a Republican lawyer whom Gov. Ron DeSantis appointed to the County Commission shortly after Gonzalez lost a Primary for the Florida House in late 2022; and elementary school teacher Claudia Rainville, who filed and qualified for the race this month.

Rainville’s fundraising ability isn’t yet known. She hasn’t yet had to turn in a campaign finance report. Between Gonzalez and Paz-Hernandez, the difference is stark.

Since taking office in November 2022, Gonzalez has raised nearly $876,000 between his campaign account and political committee, America First Florida First. As of May 31, he had about $674,500 left to spend.

Paz-Hernandez raised $8,500 through his campaign account between late February, when he entered the race, and the end of last month. Most of the money came in the first five weeks of his candidacy.

A political committee he listed as supporting his campaign in April, Miami-Dade First, raised $14,500 since it registered with the county in September.

Going into June, Paz-Herandez had close to no funding left. He said he believes Miami-Dade First, which spent all but $1,700 through the end of May, “never spent any money” to support his campaign.

Paz-Hernandez noted that while Gonzalez’s fundraising has leaned heavily on deep-pocketed corporate donors and political interests, his own depended mostly on grassroots contributions of less than $200 apiece.

“My campaign is people-led, and my donors represent a wide range of life paths, including teachers, clergy, students, nonprofit leaders and retired seniors,” he said. “I’m proud of that diversity. Additionally, almost all my donors actually live in Miami-Dade County, unlike the donors of my opponent.”

Of the 504 contributions Gonzalez received through his campaign account and political committee, 11.5% have come from outside the county.

Five percent of the 80 donations Paz-Hernandez received came from out-of-county donors. None of the contributions to Miami-Dade First were from outside the county; however, all but $205 came from political committees.

Tackling corruption and unaffordability

Paz-Hernandez took umbrage with Gonzalez’s use of taxpayer funds, particularly his decision to have two district offices, one of which is vacant and costing upwards of $71,000 a year. The other is projected to cost the county more than $1 million over nine years.

He also criticized the incumbent for allocating $10,000 in district funds to Jar of Hearts, a local nonprofit for which Gonzalez’s law firm, PereGonza, was previously listed as the registered agent by the Florida Division of Corporations.

Paz-Hernandez plans, if elected, to advocate for a new county code of ethics with stricter laws for public officials. He called Miami-Dade’s existing Conflict of Interest and Code of Ethics Ordinance “a start” in the right direction, but said it’s “not really enforceable” now and that the county needs better conflict-of-interest disclosure requirements, recusal policies, post-employment restrictions and open government laws.

He also said the Miami-Dade Commission on Ethics and Public Trust, an independent agency with advisory and quasi-judicial powers, isn’t fulfilling its purpose.

In the past two years, a multitude of current and former elected officials have come under investigation for allegedly misusing their public power for personal gain. That includes several municipal officials as well as former Miami-Dade School Board member Lubby Navarro, who faces charges of stealing $100,000 from her district, and the man Gonzalez replaced on the dais, Joe Martinez, who is going to trial this year for felony counts of unlawful compensation and conspiracy.

Both Navarro and Martinez have denied any wrongdoing. Martinez is now running for Sheriff.

“I’m really sick and tired of the culture promoted among Miami-Dade politicians that it’s OK to be corrupt and take money from special interests while forgetting about the people,” Paz-Hernandez said. “It’s unacceptable. I want to restore honesty and truth to government so people can trust their elected officials.”

Affordability is another big issue Paz-Hernandez wants to tackle. Miami-Dade is facing the “largest affordability crisis” in the country, according to Miami Homes For All Executive Director Annie Lord. Her group calculated that the county is short more than 90,000 affordable housing units, with just 14,000 units spread across 101 projects in the pipeline.

Levine Cava proposed a $2.5 billion bond issue in January to help deal with the problem, but withdrew the plan in April after facing bipartisan criticism.

That may have been politically expedient in the short term, but residents are still struggling to get by and deserve some relief, Paz-Hernandez said.

“Miami-Dade is really becoming a city for the rich rather than middle-class families,” he said. “A lot of folks in my generation are having to leave because they can’t afford rent.”

There are other options, he continued. He plans to sponsor legislation to create good-paying jobs, reduce property taxes and enact risk-mitigation programs to help cut the cost of property insurance. Miami-Dade should also provide tax incentives to homeowners who strengthen their properties against storm damage, reduce SunPass toll fees and impose a moratorium on any new tolls.

Paz-Hernandez stressed that he isn’t running for popularity purposes, even though an election is something of a popularity contest. His sole goal, he said, is to improve the lives of those living in his home county.

“My passion is that I genuinely care about people. And I love talking about problems. I love talking about policy,” he said. “But I am only interested in this job if in four years I can point to multiple accomplishments that I got done for the people of District 11. I’m not interested in getting more Instagram followers or anything like that. I am truly only interested in solving these very important problems.”

The Miami-Dade County Commission is a technically nonpartisan body, as are its elections, meaning all candidates in a given race will compete in the Aug. 20 Primary Election. If no candidate in a race receives more than 50% of the vote, the two biggest vote-getters will square off in the Nov. 5 General Election.

___

Editor’s note: This report has been updated to include information about Miami-Dade First from Paz-Hernandez.