- Andrew McGinley

- Behavioral Health Teaching Hospitals Act

- Budget

- Chad Poppell

- Crockett Farnell

- Dan Daley

- DCF

- Department of Children and Families

- Ernst & Young

- Florida Department of Children and Families

- Florida Mental Health Advocacy Coalition

- Gayle Giese

- Human Rights Defense Center

- Jeb Bush

- Jennifer Bradley

- Leon County

- Lucy Hadi

- Mental health facilities

- Mental health treatment

- Mental health treatment facilities

- Mental health treatment facility

- Mental hospital

- Mental hospitals

- Miguel Nevarez

- Nan Cobb

- Paul Wright

- Prison Legal News

- Ron DeSantis

- Shevaun Harris

- Tara Carty

- Taylor Hatch

- Tristin Murphy

- Tristin Murphy Act

Nearly 20 years after Florida’s family welfare chief was fined and resigned after her agency failed to move mentally ill inmates into treatment centers, the state is once again in court over the same problem, which has worsened since.

In an ongoing case in Leon County, the Department of Children and Families (DCF) was ordered this month to explain why it shouldn’t be held in contempt for failing to transfer Tara Carty, a 46-year-old defendant declared incompetent to stand trial, to a forensic hospital within the 15 days required by state law.

DCF General Counsel Andrew McGinley offered a jaw-dropper of an explanation. The agency isn’t in “willful non-compliance,” he said, as it would transfer Carty on time if it could. Rather the agency is physically unable to meet that deadline because none of its beds at six mental health treatment facilities statewide are available.

Carty’s case is far from unique. DCF said 772 defendants committed to mental health treatment facilities were waiting beyond the 15-day limit as of July.

The average wait time is 117 days for men and 125 days for women.

Carty, DCF noted, was 29th in line on the female wait list.

Florida law has mandated for decades that criminal defendants can be jailed for a maximum of 15 days if found not guilty by reason of insanity or deemed incompetent to stand trial. After that, they must be transferred to a mental hospital.

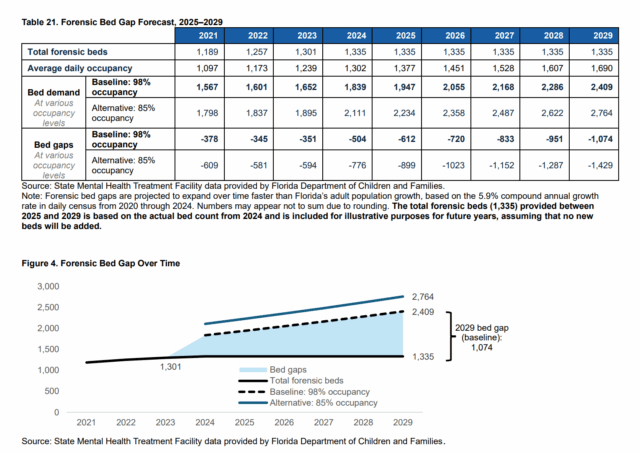

Forensic commitments of mentally ill inmates have surged by 74% since 2020, DCF said in its court filing, but the state still has only a little more than 3,000 beds.

McGinley argued that contempt orders won’t fix what is fundamentally a legislative issue, that courts can’t compel DCF to spend money or create beds beyond what lawmakers have funded.

Under Florida statutes, the DCF Secretary and the heads of nearly every other state agency must submit yearly budget requests to the Legislature and Governor “based on the agency’s independent judgment of its needs.”

DCF funding specific to bed capacity has varied over the past half-decade. Between 2020 and 2022, lawmakers apportioned between $10 million and $14.6 million to bolster and boost its forensic bed count. Ahead of fiscal year 2023-24 — when the agency later said delays peaked at 525 detainees waiting in jail beyond the 15-day deadline — DCF requested $47.3 million. Lawmakers approved $35 million.

It denoted a historic and continuing trend. Over the years, DCF has routinely requested more money to reduce the wait for mental health treatment facility beds than the Legislature ultimately provides. Sometimes the difference is vast, as was the case in last year’s budget, when DCF requested $77.8 million in nonrecurring funds and got just $9 million.

For fiscal year 2026, DCF asked for even more: $95.4 million in recurring general revenue funds to “sustain and support” bed capacity. The budget that Gov. Ron DeSantis signed in June included $78.6 million for that purpose. But there’s a catch: Just $19.6 million is cleared for immediate release, with the rest held in reserve.

Paul Wright, Executive Director of the nonprofit Human Rights Defense Center and founding editor of Prison Legal News, told Florida Politics he’s surprised no one has filed a class-action federal lawsuit yet.

“There’s been successful litigation in a bunch of states, where they came under federal court supervision with injunctions and the court told them, ‘Hey, you’ve got to do this.’ Because they’re not going to wait 25 years for the Legislature to maybe get around to doing something,” he said. “That would be the obvious next step here, a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the people being denied.”

More has been done over less

The current problem echoes a case in 2006, when Pinellas County Judge Crockett Farnell fined then-DCF Secretary Lucy Hadi $80,000 for similar delays. Under Hadi’s watch and with insufficient state funding, some detainees deemed too mentally ill to be convicted or stand trial had languished in jail without treatment for nearly three months.

During the case, Farnell accused Hadi of disobeying court orders, missing appeal dates and even charged her with indirect criminal contempt, which carried the possibility of jail time.

At the time, 237 inmates statewide — less than a third of the current count — were held illegally past the statutory cutoff. DCF then had 1,416 beds at its mental health treatment facilities. Today, the count is “approximately 3,046,” McGinley said in his court filing.

Back in 2006, public defenders and county officials warned that the delays under Hadi imperiled vulnerable inmates prone to self-harm. Lawsuits against DCF multiplied. At least one judge in North Florida threatened to deliver a mentally sick inmate directly to Hadi’s office if DCF didn’t pick them up from a local jail.

Then-Gov. Jeb Bush immediately criticized Parnell’s fine as activistic and counterproductive. The next day, however, Hadi announced her resignation. She insisted her departure was unrelated to the controversy.

Fast forward two decades, and the situation has grown grimmer at the agency now helmed by Secretary Taylor Hatch, who came to the job in February after leading Florida’s Agency for Persons with Disabilities. Her predecessor, Shevaun Harris, led DCF for four years and now runs the Agency for Health Care Administration. She replaced Chad Poppell, who stepped down in February 2021.

In March 2024, DeSantis signed the Behavioral Health Teaching Hospitals Act by Republican Sen. Jim Boyd and Republican Rep. Sam Garrison, which, among other things, required that DCF study the capacity of its behavioral health facilities. The resulting 67-page report, delivered in January, projected that the supply and demand gap for beds at Florida’s mental treatment facilities will widen at a rate notably faster than the state’s population growth.

Analysts at Miami accounting firm Ernst & Young, which prepared the report, said Florida’s mental health treatment facilities “are continuously seeing elevated levels of waitlists for civic and forensic beds.”

“To maintain the current occupancy rate of 98%, state mental health treatment facilities would need to add at least 1,602 additional forensic beds within the next five years to meet demand,” the report said. “If the state mental health treatment facilities maintain the industry standard occupancy rate of 85%, the forensic beds gap is projected to be even higher (2,034) by 2029.”

Denying unstable inmates proper and prompt treatment can be the difference between life and death. Such was the case with Tristin Murphy, a 37-year-old Charlotte County man with schizophrenia who killed himself with a chainsaw in 2021 after 63 days in prison on a felony littering charge.

Some incidents were non-lethal but left permanent damage. Inmates suffering from psychotic breaks in Colorado and Texas gouged out their eyes. In 2019, a man cut off his penis and flushed it down a Broward County jail toilet while in solitary confinement. A Tennessee man did similarly in 2022.

Murphy’s tragedy led to legislative action. An eponymous law this year by Republican Sen. Jennifer Bradley, Republican Rep. Nan Cobb and Democratic Rep. Dan Daley expanded probation and diversion options for mentally ill defendants while tightening mental health safeguards around inmate work assignments.

“The intersection between mental health and our criminal justice system is a very dangerous place for people to be,” Bradley said on the Senate floor in April. “Jails and prisons in Florida struggle with how to manage our mentally ill population, which is where most of our mentally ill are now, in our jails and prisons.”

Gayle Giese, President of the Florida Mental Health Advocacy Coalition, praised lawmakers for passing the Tristan Murphy Act. But she said more must be done, recalling the anguish a member of her group endured trying to get her mentally ill daughter moved from a county jail to a treatment center after being judged incompetent to stand trial.

“It took seven months of waiting for a bed,” she said. “While people with a mental illness sit in jail, they become more traumatized and their whole health declines.”

‘This is a systemic, national issue’

Wright, a South Florida native who served a 17-year prison sentence in Washington and began publishing Prison Legal News in 1990, said states failing to move psychologically unwell inmates to treatment facilities within the legally required timeframe is unfortunately common, and it’s led to numerous successful class-action lawsuits.

“This is a systemic, national issue,” he said. “People are sitting in jail for weeks, months, even years, where they’re incompetent to stand trial but haven’t been moved. They’re in this kind of limbo.”

In 2023, a federal court fined the state of Washington $100 million for violating inmates’ due process rights by delaying competency services and failing to add enough mental health treatment facility beds.

Three years earlier, a federal court approved a $650,000 class-action settlement for plaintiffs in a comparable California case. In California’s Contra Costa County, a Judge fined the Department of State Hospitals $17,400 for similar violations.

Other litigation over the same issue led to a judge holding state officials in contempt in Maryland, a non-monetary settlement with plaintiffs that required reforms in Utah and a judicial censure in Minnesota.

Wright noted there’s a “fairly high bar” to be determined mentally unfit to proceed in a criminal case. In Florida, under Statute 916 and Rule 3.212 of Criminal Procedure, defendants must undergo evaluations by at least two mental health experts if the judge or lawyers from either side raise concerns.

The experts, trained to test for feigned incompetence — malingering, in legal terms — evaluate the defendant’s mental state. They review records and submit reports addressing statutory factors, including the defendant’s ability to testify, grasp key aspects of the legal process, communicate with their attorneys and make rational decisions about their defense.

Only after that does the judge decide whether the defendant is competent.

“To be found incapable of assisting in your own defense or unable to understand the case, you’re either very disabled or mentally ill,” Wright said. “These aren’t borderline cases.”

Which leaves Florida, through DCF, conspicuously exposed to legal action, he said.

“I’m not aware of anyone losing these kinds of cases, because the facts are generally pretty clear, pretty obvious. These aren’t marginal cases, and the states are pretty egregious with them,” he said. “I’d say it’s probably just a matter of time before a case like this gets filed.”

Florida Politics contacted DCF for comment and information with a two-day deadline to respond. The agency’s press secretary, Miguel Nevarez, responded initially and acknowledged the request, but ceased communication after and did not provide any information by the deadline.