A bit of ancient wisdom in the legal profession holds that if the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts.

And if both the facts and law are against you?

Argue jurisdiction: tell the court that it has no business hearing the case.

Secretary of State Ken Detzner used that line to postpone the inevitable day of reckoning on whether Florida’s blind trust law violates the constitutional obligation of public officials to disclose their personal finances.

Ruling for Detzner, the First District Court of Appeal held Feb. 23 that a circuit judge who upheld the law should have dismissed the case instead because nobody was attempting at the time to rely on a blind trust to file election qualifying papers.

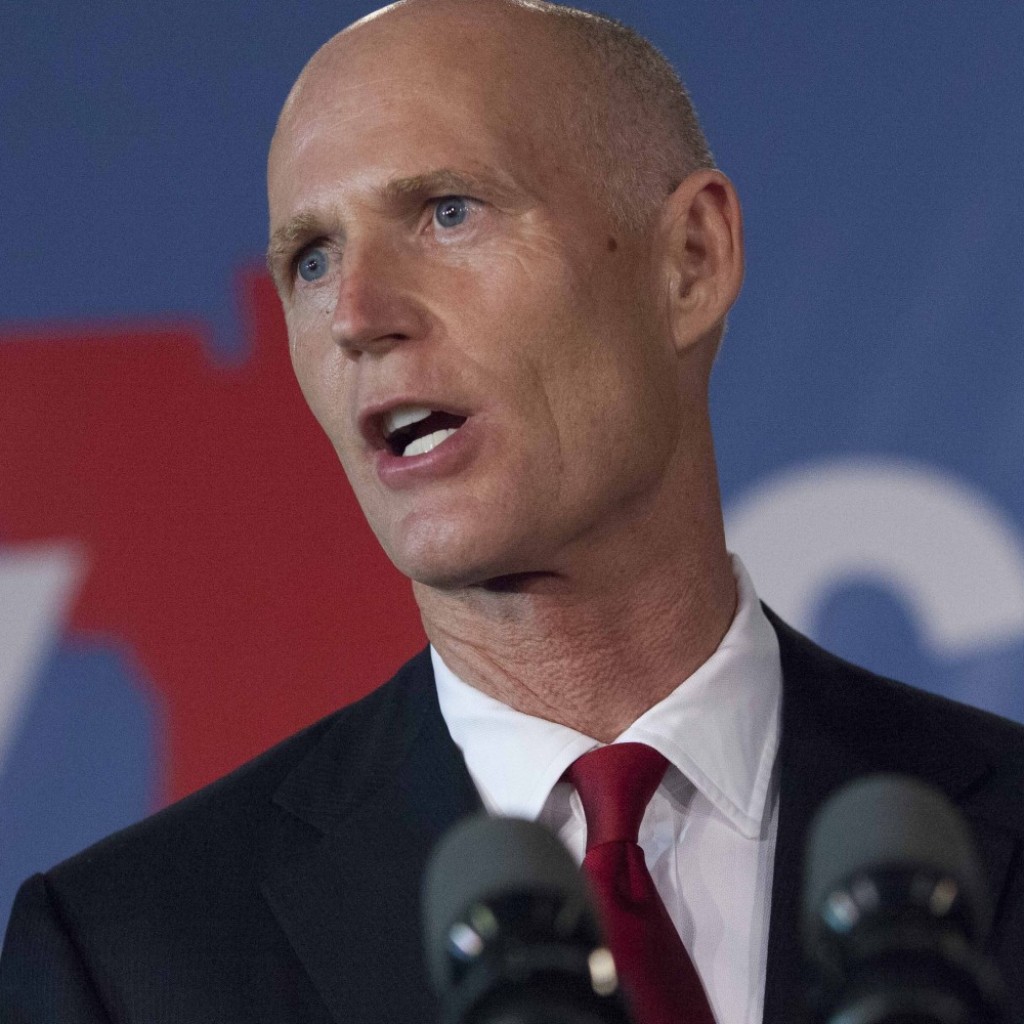

Detzner’s boss, Gov. Rick Scott, had cleverly avoided the issue by unsealing his blind trust just long enough to file for re-election. Although he wasn’t named in the lawsuit, the immensely wealthy governor is its poster boy.

But the problem isn’t going away. Every elected constitutional officer – from governor to county commissioner – is required to file “full and public disclosure” of their financial interests each year as well as when running for office. That’s in the Florida Constitution.

The court’s 3-0 opinion came with a warning from one of the judges, Brad Thomas, that the blind trust law “may likely be incompatible” with the Constitution. “Our decision today…should not be read to lend any support for the proposition that the statute at issue ensures ‘full and public disclosure,’ as mandated by Article II, section eight of the Florida Constitution,” Thomas wrote in a concurring opinion.

In George Orwell’s nightmarish novel, 1984, the fictional dictatorship of Oceania practices mind control on its people with such slogans as “war is peace,” “slavery is freedom,” and “ignorance is strength.”

(That last one is uncomfortably close to present reality. National Geographic‘s current cover story, “The War on Science,” expounds upon a flowering of ignorance in the United States. But I digress.)

“Blind trust” is equally self-contradictory. If the purpose is to discourage conflict of interest by concealing an official’s investments even from himself, the arrangement needs to be truly opaque. Florida’s law is as translucent as a gauze veil. It’s weaker than federal law in a dozen ways, most notably by allowing Scott to use his long-time investment adviser as the trustee. You could bet the bank on two things: He knows where Scott wants the money invested, and Scott knows that he knows. The only entity left blind is the public.

The 2013 law is a shell game that leaves limitless possibilities for officials to feather their nests behind the facade of a blind trust. All it takes is a wink and a nod between the official and the trustee. There is no penalty for connivance or false reporting, and no financial disclosure of any sort – not even on the total remaining value of a trust – is required after the official leaves office.

Assume, for example, that a governor wanted to make a killing in, say, private prison corporation stocks. He could wait until his last year in office, count on his trustee to buy up quantities of the stock, and then steer more contracts to that politically active industry.

Thomas helpfully pointed out another flaw:

“Although the statute requires that an initial list of assets assigned to the trust be provided to the Commission on Ethics, the electorate is not informed as to what assets will remain in the trust and what new assets may be acquired.”

“Full and public disclosure” was the key element of the ethics initiative that Gov. Reubin Askew took to the voters in 1976 after the Legislature repeatedly balked at enacting it. Three Cabinet officers had been indicted – two ultimately went to prison – over transactions that could not withstand sunlight. Askew argued that disclosure was important not only to discourage transgressions but, even more so, to “earn once again the faith of the people.”

Askew died a year ago this month, not long before his first chief of staff, Jim Apthorp, went to court to vindicate his great achievement. But even though the law is a fraud, the district court decision appears to allow no remedy.

Citizens not trained in the law will find it hard to understand why judges would duck a decision on the merits that so plainly needs to be made sooner or later. Why waste so much time and money?

Sandy D’Alemberte and Patsy Palmer, Apthorp’s attorneys, say they have several options. One is to ask the court to certify the case to the Supreme Court as a matter of great public interest. Another is to appeal the finding that there wasn’t a “justiciable controversy.”

At the least, there will be one the next time that Scott or any other subject official tries to rely on a blind trust as full disclosure. Thomas has warned them.

“There’s no excuse for any official to say, ‘I wasn’t aware I was treading on dangerous ground,'” says Palmer.

Martin Dyckman is a retired associate editor of the St. Petersburg Times. He lives near Waynesville, North Carolina.