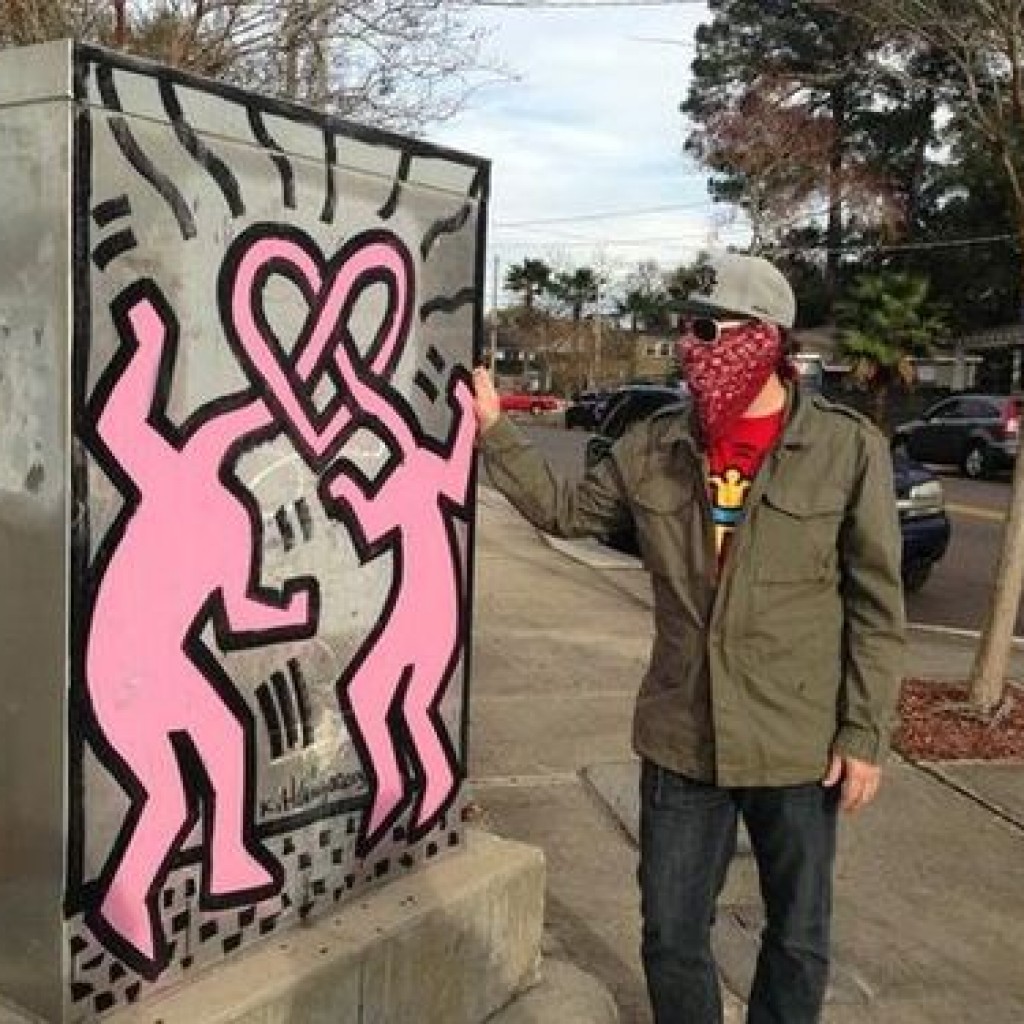

A fun little #jaxpol fight, reported on by First Coast News: Keith Haring’s Ghost Vs the Man Who Would Be Council Vice President.

At issue: the Urban Arts Program, a seeming reaction to local painter Chip Southworth, who under the guise of “Keith Haring’s Ghost,” painted Haring-esque images on the drab exteriors of traffic control boxes.

This was after what seemed like an eternity of public furor about graffiti tags and the like.

Southworth got a rep, then got arrested, making philosophical points about public space and artistic expression that some ate up with a spoon and some rejected as jejune. However, there was a happy ending, in that city officials were on board with “streetscape enhancements” and public art that befit community standards.

However, even back in 2014, there were those who urged caution.

One such party: Lee Harvey, the original artistic provocateur of Jacksonville’s alternative scene late last century. Harvey passed on in 2014, yet his words of reaction to L’ Affaire Southworth in one of his last interviews bear mentioning.

“Stalin approved of public art — as long as he was the subject,” he said from his home in New York City. “I’m not a big fan of what Jacksonville calls ‘public art.’ If it is approved by the city, then it becomes less art and more decoration.”

Perhaps Southworth sees Harvey’s words as prescient now, given his contretemps with John Crescimbeni.

Southworth believes that local artists merit consideration and set-asides. Crescimbeni, meanwhile, believes that Jacksonville’s search for appropriate public art should be more global in reach.

The project includes seven utility boxes, but Southworth told First Coast News that hundreds in Jacksonville could get painted.

Crescimbeni, calling Southworth a “rabble rouser,” cited his commitment to the “best possible public art that we put out in our city.”

That public art was always going to be in accordance with community standards. And that community was going to be the perpetual governing class, the class of capital, of people with manners and vacation homes.

Crescimbeni is right. Southworth, ultimately, is a rabble rouser in a tradition of local Jacksonville artists who are at war with the power structure, their work undergirded by an anarchic spirit.

It’s that spirit that makes their work less palatable to an establishment that wants the creative class in theory, yet in practice holds that class, in its most elemental form, at arm’s length.

As well, the era that bred people like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lee Harvey, and Chip Southworth is over. The rebellions against 20th-century commercialism seem passe in this era where consumerism and commodification are simply not resisted in the way they were a quarter century ago, when zines and punk rock split singles were the rage.

Whether Southworth gets what he wants out of this project is an open question. However, a less open question is that the spirit of Southworth’s art will resurface again. Yes, in his own work. But also in the work of others, of people influenced by him, of the rabble rousers of the era to come, challenging the status quo in ways that can’t immediately be forecast.

An example of that contextual continuum: when Southworth embarked on his Keith Haring homage, it was nothing anyone could have predicted. Nothing that anyone would have expected when Haring was painting subway cars in the dead of night. The transitory impulse, somehow timeless. Haring would never had gotten city money from Ed Koch‘s New York, either.

What a time to be alive.