Hillsborough County now has a funding framework in place to fund half of a new baseball stadium for the Tampa Bay Rays.

However, the team has yet to say whether or not they are willing to play ball.

The plan would leverage private investment to avoid taxpayer subsidies.

If the team rejects the deal, there is no other option left to provide funding opportunities to subsidize the nearly $1 billion stadium project, according to Hillsborough County Administrator Mike Merrill.

“We’ve got nothing else after this. This is the best we can do,” Merrill said during an update at the Board of County Commissioners meeting Wednesday.

Merrill and his staff were charged with identifying potential funding sources that did not require new taxpayer revenue or dip into the county’s general fund — a mandate he called “a tall order.”

The Rays are up against a deadline at the end of this month to notify the city of St. Petersburg of their intention to either move to another location or stay put at Tropicana Field. Hillsborough County’s framework is a crucial part of the team’s decision.

Merrill said the county was not dragging its feet. Hillsborough became aware of a possible solution earlier this year through a federal program known as “opportunity zone” funding. It came up under the Obama administration, and President Donald Trump’s administration implemented it. It allows certain areas designated by the U.S. census as opportunity zones to use private investments to fund new development.

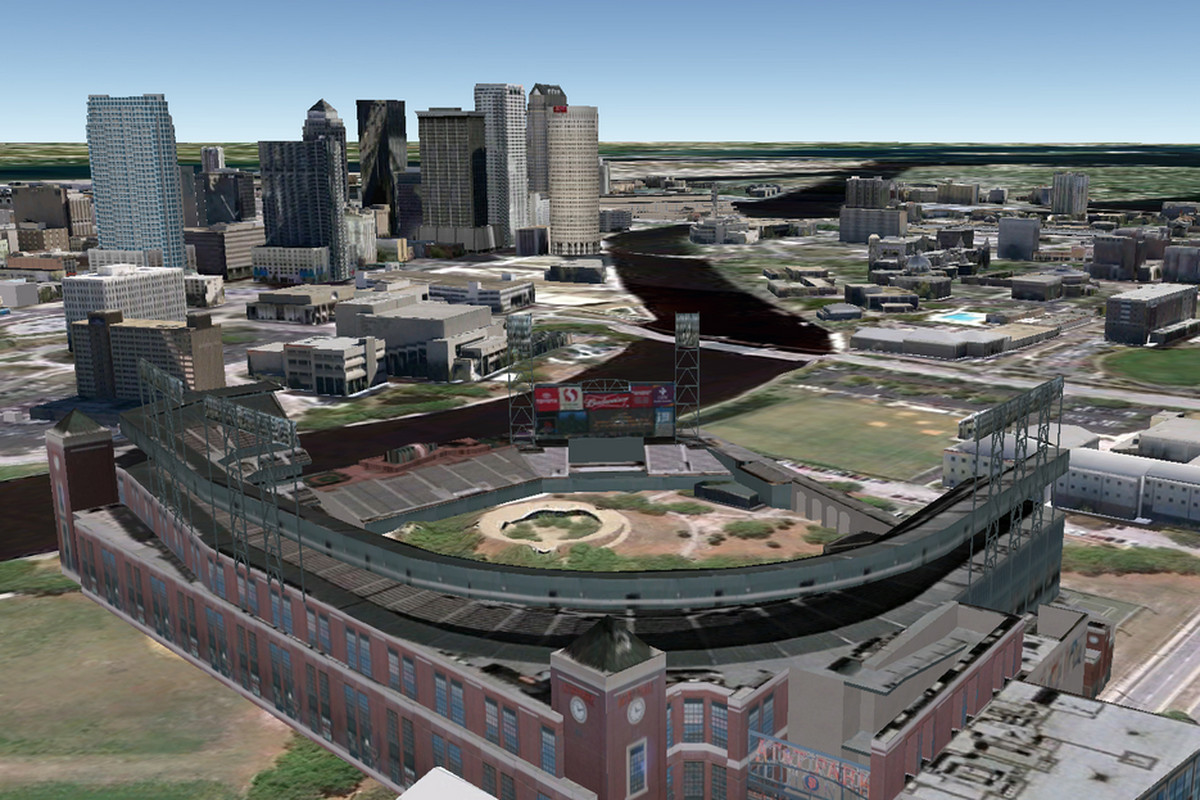

The proposed Ybor City stadium site meets that requirement, but the county only just found out.

Under the framework, the Rays would pay for half the cost of land acquisition and funding for a new stadium. The remaining funding would come mostly from opportunity zone investments as well as through private investments from Ybor City landowners through voluntary tax assessments.

The funding would also rely in part on the financing from two Community Redevelopment Areas — Ybor City 1 and Ybor City 2. Those zones, created in 1988 and 2004, respectively, use increasing property values to fun economic development. The funds cannot be used for any projects outside the district, and therefore, the county does not consider it a new public revenue source.

But even if the Rays bite, Merrill said there’s still a lot that could tank a stadium deal. First, Hillsborough County and Tampa will compete with other local governments across the nation for private investors. Those investors will base investment decisions on where they can get the most bang for their buck. The stadium deal might not make the cut.

Second, the deal relies on Hillsborough County Commissioners to in essence let the Rays operate a stadium without paying property tax, which would be a massive hit to the county’s potential revenue.

Without property tax immunity, Merrill said the project would not be financially feasible for the Rays’ ongoing operations in a new stadium.

There’s also the issue of the ticking clock. Because the deal came together in the eleventh hour, the Rays will likely need to get an extension on its agreement with St. Pete to explore alternative stadium sites. Without a deal, the team is contractually obligated to play ball at Tropicana Field through the 2027 season and is barred from negotiating with other cities or counties on a new park.

The stadium deal has been a constant source of controversy for years. The Rays have been trying to get a new stadium since 2008 when voters rejected a funding plan for a new waterfront stadium at the Al Lang Stadium site in downtown St. Pete. From there, the team set their sights on brokering a deal with St. Pete to be able to consider other parts of Pinellas and Hillsborough counties for a new potential location.

In recent months, the Ybor City site as fueled the controversy. Hillsborough County Commissioner Ken Hagan has been the county’s point person on stadium negotiations and has been accused of conducting backroom deals that undermine potential investors and favor a small group of Hillsborough landowners.

Further, because he is an elected official, Florida open government laws bar him from discussing updates with other commissioners outside of formal meetings, which he would not do because making details public could threaten ongoing negotiations.

Hillsborough County Commissioner Pat Kemp offered a motion to remove Hagan from his position leading negotiations and instead install Merrill as the lead. Merrill, a county staffer, is not bound by open government laws and would be able to update commissioners outside of the sunshine freely.

Kemp’s proposal enjoyed some support. Newly elected commissioners Kimberly Overman and Mariella Smith agreed it might be best to pass the reign to Merrill. But Hagan was absent for the meeting, and the majority of the board instead opted to take up that conversation at the board’s first meeting in January when Hagan will have a chance to defend himself and make a case for maintaining his negotiating authority.

By then, Smith pointed out, the county would know whether the Rays planned to continue negotiating with the county under the proposed financing framework. Until then, she said, there might not even be a point in having the conversation about Hagan.