Robert Earl DuBoise packs a few extra bag lunches and stows them in his truck to give to homeless people he sees around the Tampa area where he works. The bags contain things that won’t spoil in the summer heat: canned meat that can be opened by hand, cookies, crackers, bottled water.

Some days, he does handywork for his neighbors, free of charge, or drives their kids to school. They’re small kindnesses, but they’re the most he has to offer for now.

“I just want to be helpful, help my family and do what I can,” he told Florida Politics. “I just stay positive and focused on moving forward.”

DuBoise lives at the Sunny Center, a modest complex operated by and for people released from wrongful imprisonment. He lives in a little yellow house, one of four individual units on a half-acre lot.

He has been there since his release from Hardee Correctional Institution in Bowling Green last September.

Tuesday marked a year since DNA evidence exonerated DuBoise for the 1983 rape and murder of a young woman in Tampa. Just 18 at the time of his conviction, he turns 57 next month. He spent all but 20 of those years behind bars.

He has tried to get an apartment, but because of the enormous gap in his history, it has been difficult.

“They don’t understand how I wasn’t on the radar for 37 years,” he said. “It’s like I don’t even exist.”

Next year, he could receive $1.85 million for the time he lost.

Florida Democratic Rep. Andrew Learned of Bradenton and Republican Sen. Jeff Brandes of St. Petersburg last month filed twin bills for consideration in the 2022 Legislative Session that, if approved, would clear payment to DuBoise.

The bills are classified as “claim” bills or “relief acts,” as they are intended to compensate a person or entity for injuries or losses caused by the negligence or error of a public officer or agency.

They often arise when appropriate damages due to a person or entity exceeds what is allowable under Florida’s sovereign immunity law, which protects government agencies from costly lawsuits.

Under Florida law, a wrongfully convicted person found innocent by a prosecuting attorney or administrative court judge is entitled to $50,000 for each year they spent behind bars.

“Is that enough? Of course not,” Learned said Thursday. “We took his life, liberty, everything. He’s got nothing, and it’s our fault. This is an obvious thing to do.”

Learned described the bipartisan effort to repay DuBoise for the time the state took from him as “a no-brainer” and something for which he has heard nothing but support among his House peers.

Normally, legislative action wouldn’t be necessary to get DuBoise paid, but because of the state’s “clean hands rule,” which denies compensation for exonerees with more than one nonviolent felony, DuBoise is ineligible for automatic recompense. One year before he was charged and convicted of the crimes for which he spent two-thirds of his life in prison, while he was still a minor, he was convicted of burglary and grand theft and placed on probation.

As DuBoise has told the story, that conviction came after he walked into a house that was for rent and walked out to find police.

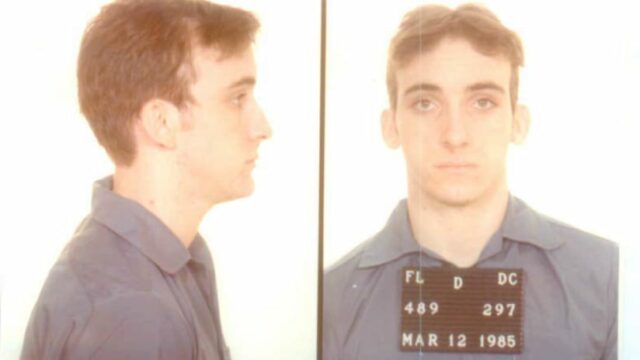

DuBoise was initially sentenced to death in March 1985 for the rape and murder of 19-year-old Barbara Grams. Prosecutors used two pieces of evidence to convict him that are today considered leading causes of wrongful convictions: an apparent bite mark, which forensic odontologist Dr. Adam Freeman later concluded to not be a bite mark; and since-discredited testimony from a jailhouse informant.

The Florida Supreme Court vacated DuBoise’s death sentence in 1988 and resentenced him to life. By that time, DuBoise had spent three years on death row within earshot of some of Florida’s most notorious killers.

Grams’ body was found along a 2½-mile route she walked to and from work. She had been bludgeoned in the head with a wooden beam.

Police canvassed the area and spoke with people who knew her. They put together a list of nine suspects, DuBoise among them. His mother gave him an alibi, saying he was home with her at the time of Grams’ murder, and no witnesses said they had seen him out that night.

Fingerprints at the crime scene weren’t a match for DuBoise. Neither were hairs found on Grams’ body.

But police zeroed in on what looked like a bite mark on Grams’ left cheek. DuBois consented to providing a mold of his teeth to compare with the mark. A forensic dentist said DuBoise’s teeth matched the mark, and he was arrested.

DuBoise’s cellmate while he awaited trial, Claude Butler, testified that DuBoise has talked of sleeping with a woman, but denied murder. Butler was later offered a plea deal, received a sentence reduction to time served and immediately released after his testimony.

DuBoise always maintained his innocence. In 2006, he filed a motion for post-conviction DNA testing. The state said all of the evidence used at his trial, including a rape kit, had been destroyed in 1990.

But in 2018, the Innocence Project and Conviction Review Unit at Tampa State Attorney Andrew Warren’s office began to reinvestigate the case, and an attorney at the CRU uncovered unused, preserved rape kit samples at the Hillsborough Medical Examiner’s Office.

In August 2020, DNA testing of the samples excluded DuBoise, prompting the state to file a joint motion with DuBoise’s counsel to reduce his life sentence to time served.

Testing of the rape kit flagged the DNA profile of another person, unconnected to DuBoise, who is now a “person of interest” in the reopened case.

Asked whether he and others state lawmakers are considering future action to close the many cracks through which DuBoise’s cases was permitted to fall for nearly four decades, Brandes said, “Absolutely.”

“There’s a lot of lessons learned here,” he said. “This is why we need these reviews. This was an injustice. This was not justice. And we need to be making sure we’re doing everything we can to prevent injustice from happening again.”

Those who wrongly convicted and imprisoned DuBoise are long gone by now. For his part, DuBoise said he maintains no resentment for the wrong done to him.

“When things happen, you have to move on,” he said. “So, I’m not bitter about it. I don’t hate anybody. Right now, all I’m trying to focus on is getting my life back on track and to keep it there.”

By passing Brandes and Learned’s bills, the Florida Legislature would acknowledge that “as a result of his physical confinement, Mr. DuBoise suffered significant damages that are unique to him, and that the damages are due to the fact that he was physically restrained and prevented from exercising the freedom to which all innocent citizens are entitled.”

Beyond monetary compensation, the bills also provide that tuition and fees for up to 120 hours of instruction at any career center or state college would be waived for him should he choose to enroll in classes.

“There’s no reason we should punt it,” said Learned, one of the Florida Legislature’s preeminent criminal justice wonks. “Is $1.9 million a lot of money? Yes. But anybody who balks at that, I would just ask them candidly, ‘Would you trade 37 years of your life for that? I don’t know anybody who would say, ‘yes, sign me up. I want to go sit in an unairconditioned cell for 37 years, some of it on death row next to Ted Bundy.’ It’s an easy question when you frame it like that.”

DuBoise hopes to receive the money. It would be life-changing, but he’s not waiting on it. He’s taking renovation and repair jobs, doing electrical work, plumbing, installing the odd ceiling fan — getting on with his life as best he can for now. But it’s hard.

“I don’t really have a business,” he said. “I’m just going by word of mouth. They see my work; they pass it on to the next person, and they call me.”

Adjusting to a world nearly 40 years in the future from where he left off has been challenging.

“They didn’t have cell phones when I went to prison, and they didn’t have Walmart and Home Depot and all of these places, so it’s a lot to take in,” he said. “It’s like coming to a whole new world and readjusting. Everything’s changed.”

Still, DuBoise’s eyes are set forward. He’s moving on. With the money he hopes to receive from the state, he plans to buy a house and settle into his new life.

“Then I don’t have to worry about will people rent me an apartment again,” he said. “And secondly, I want to help my family and do what I can to invest, save and try to build a future for myself.”