We’re all familiar with the story of the Marquis de Lafayette, whose troops and efforts helped change the course of the American Revolution. Most Floridians, except those with extensive knowledge of Tallahassee, have no idea about the intermingling of fates between the Marquis and the young territory of Florida.

At the heart of the story is the $200,000 that Lafayette paid out of pocket to finance his efforts to aid the American experiment, for which he refused compensation or reimbursement.

After the war, Lafayette returned home and assumed a military role for several years. In the early days of the French Revolution, he played a central part, serving in the National Assembly and drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

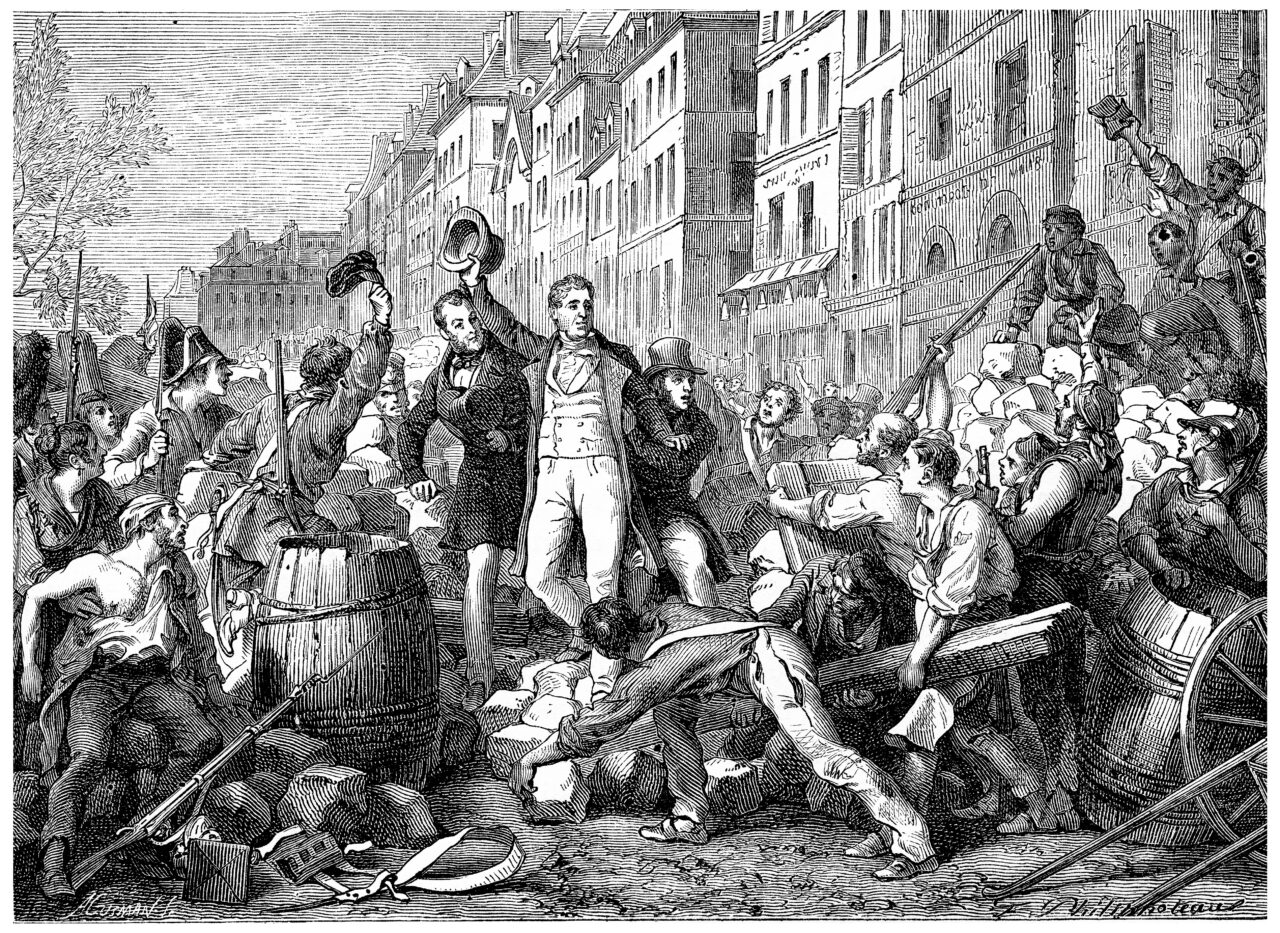

But Lafayette was a moderate who advocated for a constitutional monarchy, and when the Revolution turned violent, he saw little in his French future that didn’t involve a guillotine. Dubbed too conservative for the revolutionaries, he fled across the border to Austria, where he was immediately arrested and imprisoned as a radical and enemy of France.

Revolutionaries seized his lands and fortune during his incarceration, leaving him and his family in economic straits. Pressure mounted on both sides of the Atlantic for America to come to his aid. It was only fitting for the fledgling country he’d helped establish to respond in kind, and Americans wholeheartedly agreed.

In its first effort, Congress granted Lafayette back pay in 1794 at a General’s rate of slightly more than $24,000. Realizing that this amount did little to solidify Lafayette’s family’s financial state and that the amount was a poor return on his investment, Congress tried again in 1803.

America was cash-poor but wealthy in newly gained territory, and Congress could only make a gift of property. They allocated 11,520 acres of public land in the new Louisiana Territory with the expectation that the General could liquidate some of the property quickly, live on the remaining portion and use the funds to shore up his financial situation.

The unspoken idea was that residing there would make the surrounding areas more attractive to land buyers. After multiple battles over clear title and ownership, he was able to sell enough land 11 years later to put him in a position of security. He also never lived on his lands, choosing to remain in France.

Again, time and life in France weren’t kind to his fortunes. As an older man, he often took comfort in the memory of the republic he’d helped found, and his American friends looked to Congress to help him see America while he still could.

They passed a resolution to declare him an honored guest of the country and provided a ship for his journey. But word reached America that Lafayette would rather have the money for the boat, and requests went back to Congress for more help. Congress provided the ship for his passage and went to work on larger pieces of the plan.

Debate in Congress over how much money to award the Marquis for his service went back and forth. One representative, attempting to downplay his contributions and minimize compensation, proposed a halt to negotiations while they took time to “find out the extent of his services.”

In 1824, Congress allotted LaFayette $200,000 and a township of land (approximately 23,000 acres) in any unsold public domain to call home. Thomas Jefferson convinced Lafayette to keep most of his money in U.S. Treasury bonds as “nothing was safer,” thus slowing the flow of funds from the treasury. Once was a coincidence, twice a habit. Each gift presented to the Marquis came with a means of feeding the federal coffers hidden inside.

Then it was time to find the Marquis some land.

Florida was America’s latest territorial jewel and it takes some gymnastics to follow the process of how it was acquired. The U.S. purchased Florida from Spain by assuming $5 million worth of debt owed for damages to Americans by Spain. These damages would not exist had Americans not illegally invaded Florida in a botched attempt to take the territory by illicit means.

The rush to recoup the cost of acquisition via land sales was on.

Florida’s most vocal cheerleader was Territorial Representative Richard Keith Call, former aide to Military Governor Andrew Jackson and future civilian Governor of Florida. Part of Call’s job was to speed those land sales for the federal government.

He also had the ear of Lafayette. If he could convince the Marquis to accept his township grant in Florida, using the Louisiana model as a template, land near the estate of such a prominent figure would undoubtedly increase its value. There’s also a distinct possibility that you could benefit from the process if your name is R. K. Call.

After declaring, at Call’s urging, Florida the place best suited for the Marquis, James Monroe tasked Colonel John McKee, a Congressman and land speculator from Alabama, with finding an estate for Lafayette in the new territory. It’s worth noting McKee played a prominent role in the Patriot War, a filibustering effort that incurred the earlier-mentioned $5 million in damages against Americans.

The area of choice was abutting Tallahassee, the territory’s new capital, a site newly wrested from Enemaltha, leader of the Tallassee people, by Gov. William Pope Duval. This site, which Lafayette never saw, suited him. At the time, the area surrounding Tallahassee was some of the finest growing lands in Florida, a fact that raised the cache and potential value of the plot.

Despite many encouragements throughout this land-gifting process, Lafayette never intended to expatriate himself to the U.S. and viewed the land as something to sell rather than settle, the same as he’d done in Louisiana.

There’s a strong possibility those pushing for the Tallahassee location were counting on this idea. Lafayette’s good friend Call even put a lowball bid on half of the township, which Lafayette turned down, unwilling to take anything short of $150,000 for its entirety.

Not attaining his desired price, Lafayette launched an experiment with his new land. An unabashed abolitionist, he was disturbed by the growth of the plantation system in the U.S. and disgusted by chattel enslavement. Except for the brief British ownership of the colony, enslavement of the antebellum sort had not existed in Florida before the U.S. annexation.

He believed that he could build a more economically feasible replicable model, using “free, White, and on the whole cheaper labor” in the form of European immigrants. Rather than cotton, they would grow grapes, olives and mulberries in addition to raising silkworms as they had in Europe. Call, with lands nearby, gave at least a passive endorsement of the project.

As with many Eurocentric plans in Florida, the new settlers from Normandy were woefully unprepared for the climate and challenges awaiting them here. The colony fell apart in less than two years due to poor decisions in crop selection, the lack of a physician and general intolerance of heat and humidity.

Lafayette died shortly after, and the family trusted the lands in the care of a group of speculators in 1834. This group tried for 10 years to build the value of the land to the agreed-upon price Lafayette had set years earlier. But national economic woes and the Second Seminole War left the heirs of Lafayette with only two-thirds of the price the Marquis had set and the speculator group bankrupt.

There are no records of direct involvement on Call’s part to benefit from Lafayette’s land, but given the circumstances, it’s certainly not a reach.

First is the closeness to Tallahassee, the western edges of the property abutting the town, which should have made it quite valuable. Next is the proximity to The Grove, Call’s plantation, which, combined with Lafayette’s township, would present a sizable parcel for development.

Third is the involvement of McKee, who, along with George Mathews, had launched a covert war to wrest Florida from Spain to gain land and human property in the form of escaped enslaved people living freely in Spanish Florida. Although no implications of direct participation on McKee’s part exist, Mathews was a prominent figure in the Yazoo Land Scandal while serving as Georgia’s Governor, with McKee serving as an “Indian Agent” of the area in question.

Finally, there’s the knowledge that Lafayette’s primary concern was to sell the land. Association and prior knowledge provide motive, means and opportunity for a land grab. Only Lafayette’s stubborn insistence on $150,000 hampered the probable efforts.

Although he never laid eyes on Florida, Lafayette’s name endures throughout Tallahassee. For his part, Call went on to become Florida’s third and fifth civilian Governor, establishing the precedent for those who followed in that attempting to enrich oneself via the federal government was not only accepted but embraced and often rewarded with public office.