- ACLU

- American Civil Liberties Union

- Byron Donalds

- Chuck Clemons

- clerk of courts

- Crime and Justice Institute

- Dartmouth College

- driver's license suspensions

- Eileen Higgins

- FFJC

- Fines and Fees Justice Center

- Grover Norquist

- Harris Levine

- HB 397

- House Bill 387

- Insurance Research Council

- Ker-Twang

- LendingTree

- miami dade county

- National Bureau of Economic Research

- Peter Jones

- Revenue Estimating Conference

- Ron DeSantis

- Sarah Couture

- Steve Leifman

- Steve Mello

- The Zebra

- Tom Wright

- University of Alabama at Birmingham

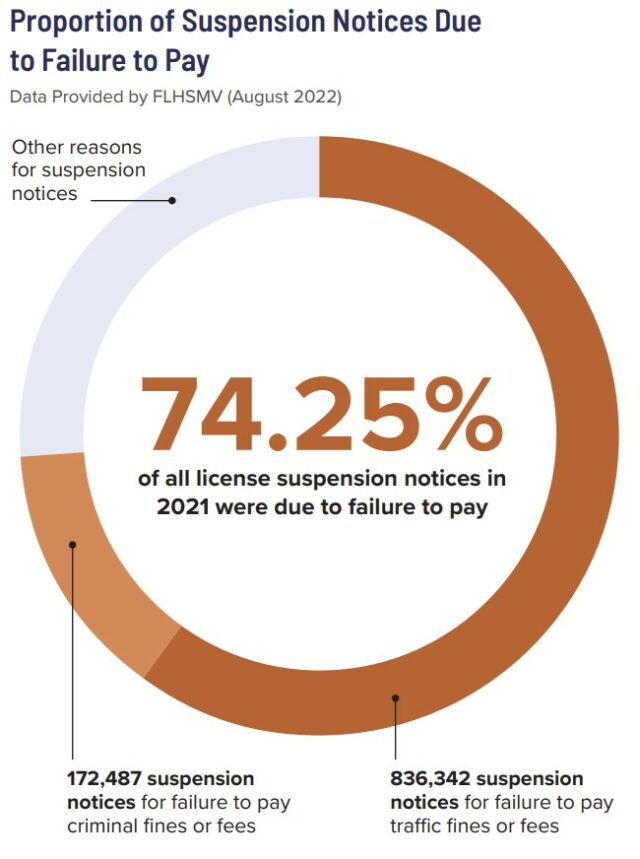

As last year ended, more than 716,000 Floridians — one in 24 driving-age adults — had suspended driver’s licenses not due to dangerous roadway behavior — but for nonpayment of fines and fees.

Without a policy change, most will not regain their driving privileges for years. The Fines and Fees Justice Center (FFJC), whose Sunshine State office is in Tampa, found more than two-thirds of the driver’s license suspensions Florida handed down in 2016 remained in effect in 2019.

Over that stretch, economists estimate Florida missed more than $1 billion in consumer spending. Florida’s most vulnerable residents also disproportionately lost money and faced related hardship.

Suspensions for fine and fee nonpayment make up the preponderance — 75% — of all suspended licenses in Florida. Just 3% are for dangerous driving, including DUIs.

It’s a problem with a clear solution but a complicated road ahead, according to FFJC Florida State Director Sarah Couture and a new report the group published Wednesday. Florida needs to eliminate its debt-based driver’s license suspensions policy, she said, which is nothing close to the “velvet hammer” proponents of keeping it believe it to be.

“It’s more like Thor’s hammer,” she said. “They think it’s a tool to compel people to pay, but we know that’s not the case because people’s licenses are staying suspended for a long time.”

Impacts on the state

Florida loses nearly half a billion dollars in consumer spending annually due to suspended debt-based driver’s license suspensions, Steve Mello, an economics professor at Dartmouth College and faculty researcher at the National Bureau of Economic Research, told state lawmakers in a 2021 letter.

People who have their licenses suspended spend 2.2% less annually. Using state and credit bureau records and data from the American Community Survey, Mello found that Florida’s yearly consumer spending shortfall now is roughly $491 million.

The state also forgoes sales-based income. Take one quantifiable revenue stream: gas taxes. Alabama, which has a license-suspension policy like Florida’s, forwent about $140 per driver in 2021 due to lost gas taxes, according to a January 2022 study by Peter Jones, an assistant professor in budgeting, finance and econometrics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Court costs associated with handling license suspensions in Florida were $40 million last year alone, the James Madison Institute found in a collaborative study with the Reason Foundation.

Prior reporting by the FFJC revealed Florida’s driver’s license suspension policies especially impact the poor and people of color. The group said an analysis of state records showed “Black people have a suspended driver’s license on average 1.5 times the rate they are represented in the general population.

Speaking with Miami Today in September 2020 about the issue, Miami-Dade County Judge Steve Leifman, who rules over traffic and criminal cases, said Florida has “reached a tipping point” on the issue.

“They’ve put the burden of taxes on some of the lowest-income people who cannot afford it, so they don’t pay their ticket, continue to drive, and end up having collateral impacts like jail and other issues,” he said. “It’s costing the state more money than if we lowered the cost and collected the money.”

Impacts on residents

Florida’s less well-to-do residents face a confluence of difficulties. Beyond just having less money with which to pay fines and fees, they are less likely to be homeowners and more likely to move often, which can lead to missed tickets and court notices in the mail.

Without the ability to commute to work by car or use their vehicles for vital tasks such as taking their children to school and going to the doctor, poorer Floridians face what Harris Levine of low-income aid company Ker-Twang calls a “debt spiral.”

Earlier barriers beget others. Florida drivers pay the third-highest premiums in the U.S. behind Louisiana and Michigan, according to a January study by a subsidiary of online lending marketplace LendingTree. On a related note, it also has one of the highest rates of uninsured drivers (about 20%).

The result is a chicken-or-the-egg predicament.

Florida’s suspension practices are a major contributing factor to the state’s high insurance premiums. When a Florida motorist has their license suspended — you guessed it — insurance companies raise their premiums, on average, by a jaw-dropping 67% for at least three years regardless of the reason for the suspension, research by Austin-based insurance comparer The Zebra found.

“The uninsured rate in Florida is costing all Florida drivers,” the FFJC report said, citing data from the Insurance Research Council, which estimates that “uninsured drivers add an average of $78 to insured driver premiums each year.”

“Ending debt-driven license suspensions in Florida will reduce everyone’s auto insurance premiums by eliminating a significant cause of uninsured drivers,” the report added.

Spinning a revolving door

The policy also contributes to recidivism. According to a July 2022 report by the Crime and Justice Institute (CJI), Florida has one of the largest supervised populations — people on probation or parole — in the country. Forty-eight percent of that group today will end up back in prison due to a probation or parole violation.

Most violations are based on technicalities, not added crimes, a fact that prompted the Florida Department of Corrections to engage the CJI for solutions in 2019.

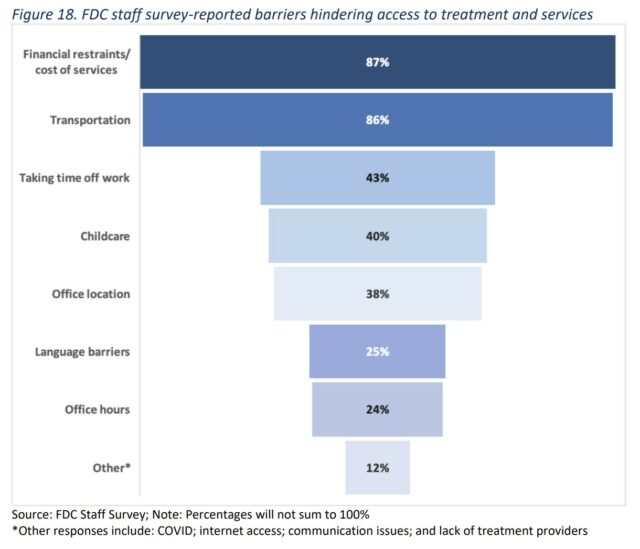

Stakeholder interviews the CJI conducted on behalf of the department revealed that driver’s license suspensions are a significant barrier for Florida’s supervised population. Eighty-six percent of respondents cited transportation difficulties as a factor preventing parolees from accessing services and staying out of the system. Only financial difficulties ranked higher, at 87%.

Probation officers, in turn, reported during focus group interviews that their supervisees have limited access to public transportation — a problem widespread in Florida, including its dense, metropolitan areas — or that public transportation is accessible but not a realistic possibility due to time constraints.

In its recommendations to the Department of Corrections, the CJI said Florida lawmakers “should adopt legislation to mitigate or completely avoid driver’s license suspensions that occur for non-driving related behaviors.”

The institute noted that in 2021 alone, Governors in Arkansas, Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, Utah and Washington signed legislation curbing or dropping debt-based driving restrictions.

State and local lawmakers here have tried for years to do similarly. In 2020, two Republicans — Sen. Tom Wright and U.S. Rep. Byron Donalds, then a member of the Florida House — filed legislation to end debt-based license suspensions. The measures died in committee.

The next year, Miami-Dade Commissioner Eileen Higgins led a task force to brainstorm local workarounds; the resulting report came out in July.

There was a minor breakthrough in 2022 when Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a new law (HB 397) by Republican Rep. Chuck Clemons easing how local governments can offer payment plans to indebted motorists. Rather than having to pay all costs upfront, people who owe money for fines and fees can pay the greater of either $25 per month, or 2% of their annual income, divided by 12.

Some counties like Pinellas and Hillsborough already have payment plans or suspension-preventing programs in place. Palm Beach County has enacted policies to reduce its rate of suspensions through the use of digital hearings, payment plans and changing how it informs motorists of a pending suspension.

While eliminating license-for-payment policies may seem a liberal concept on its surface, several states with conservative-led Legislatures — including Idaho, Montana, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming — have enacted or considered statutes either stopping or significantly limiting the practice. In 2018, the first full year California rolled out its own such policy, revenues from fine and fee collections grew nearly 9%. Others like Georgia, Maine, Vermont and the District of Columbia have ended automatic license suspensions for nonpayment of costs unrelated to traffic violations.

Numerous conservative and libertarian advocacy groups have called for the change. Among them are Americans for Prosperity and the American Legislative Exchange Council.

Americans for Tax Reform President Grover Norquist said the criminal justice system should punish lawbreakers, but it must give people a chance to work, pay their debt and move on.

“The status quo does not put public safety first; it traps people in a government debt system and wastes police time on tax collection. It is time for all states to end driver’s license suspensions for court debt,” he said in a statement.

The clerks’ conundrum

The natural question readers may ask themselves at this point is, “Why hasn’t Florida already fixed this problem?” The answer is uniquely Floridian.

Florida’s biggest obstacle to fine and fee reform is the funding formula for all 67 court clerks throughout the state, which is in the Florida Constitution. And yes, their primary source of funding is court fees, including fees related to licensing suspensions. The Constitution also provides that the Legislature may apportion “adequate and appropriate supplemental funding from state reserves.”

According to Couture, that funding model is the main reason lawmakers cite in opposing legislation to end debt-based driver’s license suspensions.

Clerk offices in Florida, which keep county records and perform thousands of public and governmental duties, have faced funding issues for years. But the divide between what they need and what the state gives them based on projections by the Revenue Estimating Conference is widening.

“It looks like the stock market crashing,” Couture said. “My counterparts in New York, Nevada and New Mexico — this isn’t something they have to deal with in their work. It’s an added layer here in Florida.”

Changing the funding model soon will require a three-fifths vote by both chambers of the Legislature or a voter initiative. The Taxation and Budget Reform Commission and the Constitution Revision Commission, which next meet in 2027 and 2037, respectively, can also make the change.

Studies have shown clerks’ offices collect more revenue when their states do not suspend driver’s licenses for unpaid fines and fees. That includes a 2021 analysis comparing Texas municipal courts that issued license renewal holds for nonpayment with those that didn’t. The courts that didn’t withhold license renewals collected $45 more per case than their stricter counterparts. A separate study in Tennessee reached a similar outcome.

A January 2020 memorandum from the Florida Clerk of Courts Operations Corporation, which helps to oversee clerk offices statewide and make recommendations to the Legislature, estimated that ending debt-based license suspensions could reduce funding by $21 million to $49.5 million. But the memo also noted that allowing people to drive to work could improve compliance with fine and fee payments and reduce workloads for courts, which together would create a positive fiscal impact.

In its 2021 report on the issue, the American Civil Liberties Union pointed out the Florida Clerk of Courts Operations Corporation analysis “did not estimate the potential savings from no longer administering and enforcing more than 1 million license suspension notices on an annual basis.”

Couture added that doing away with driver’s license suspensions will not erase what people still owe in fines and fees.

“The people are still responsible for paying,” she said. “This just gives somebody their license so they can go to work. A lot of jobs just require a license even if there’s no driving involved. They see it as a reliability mechanism.”

One comment

Richard Bruce

February 21, 2023 at 2:09 pm

I have a family member who owes fines before getting license renewal. It’s a burden on many people. If forgiven, what’s the point of the fine? Also, the time to pay the fine shows the offender the value of the license and maybe they will follow the law.

Comments are closed.