After years of legislative inaction, Miami Lakes is poised to take a legal stand to protect its residents and their properties from home-shaking blast mining.

Town Council members will consider a measure by Steven Herzberg to challenge the constitutionality of Florida Statute 552.36, which prohibits residents from pursuing legal claims in court for damages by the use of explosives at nearby limestone quarries.

If approved, the item would authorize the town to file a lawsuit — or join existing litigation against the state law — that has effectively blocked property owners from seeking redress for cracking walls, rattled foundations and emotional distress stemming from mining detonations in northwest Miami-Dade County.

Herzberg told Florida Politics on Thursday the item is likely to receive sufficient support June 17, noting that he and three other members of the seven-seat Council have served on the town’s Blasting Advisory Board. It was also a top issue for candidates in the town’s election last year.

“While the Council is almost brand new, that Council also said, ‘Yes, this is a roadmap. We have to do this. Enough sitting around,’” he said. “I’m confident it will move through, and we’ll see where it goes from there.”

Florida law today, under the statute in question, requires claims about property damage due to blast mining to be handled exclusively through the state’s Division of Administrative Hearings, which generally adjudicates administrative and workers’ compensation disputes.

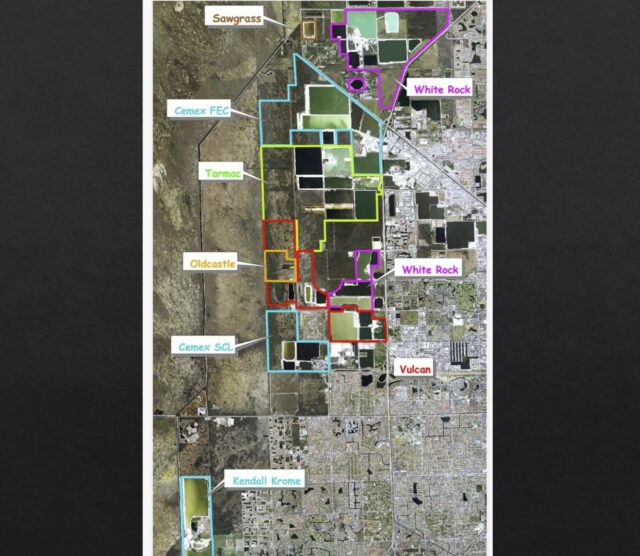

That setup essentially blocks Miami Lakes and other quarry-adjacent municipalities like Doral, Miramar and Palm Springs North from taking the state’s numerous mining companies, which operate eight quarries in northwest Miami-Dade, to court over infrastructure and financial harm.

Herzberg argued the statute “strips an entire class of claims from the court” and reroutes what is clearly a judicial issue to an administrative process under the executive branch.

He also made clear that his goal is not to shut down or imperil the mining industry, which Miami Lakes recognizes as “essential” to Florida’s economy and infrastructure.

“We are not calling for operations to stop,” he said. “We are calling for equal protection under the law for the accountability of actions of the industry.”

Efforts to reform state policy on blast mining have repeatedly stalled in Tallahassee. A February 2024 workshop in the House on a bill aimed at limiting the strength of explosions failed to produce any formal committee hearing.

Lawmakers heard from industry professionals who maintained that while quarry explosions may cause cosmetic damage to buildings close to dig sites, including small cracks in drywall and other comparatively weak materials, they’re not strong enough to cause structural damage at the currently allowed level.

Residents and members of the Blasting Advisory Board argued that any damage, including photographed cracks in the concrete, floors and roofs of their homes, is unacceptable.

The bill died unheard, as did related legislation this year by Hialeah Gardens Sen. Bryan Ávila and Miami Lakes Rep. Tom Fabricio — the latter of whom has filed bills in each of the past five Sessions to tackle the blast mining issue.

“Our view is pretty simple. We believe that the limestone quarry blasting limits in the state are generally fine,” Fabricio said during the workshop. “However, in situations where we are about 1,000 yards from a residential community, where the homes are shaking every day and causing damage to the homes, it’s a problem.”

Herzberg’s item challenges “blanket immunity” that it says Florida law provides for “activities which may be causing harm to residents and properties without affording them an opportunity to be heard in a court of law.”

He said it shouldn’t take long for the city to sue after approval of the measure, which he estimated would cost the town $50,000 to $100,000, depending on whether other municipalities join in on the suit or welcome Miami Lakes onto theirs.

That’s markedly less than what the companies mining limestone, which is used in virtually every construction project in Florida, have made in state-level contributions to elected officials and political committees.

Cemex, a Mexico-headquartered building materials company operating in Miami-Dade, made $347,0000 worth of in-state political donations between 2001 and early 2024.

White Rock Quarries, the largest mining company in the county, contributed $480,000 since 1996. Nearly half of Florida’s 40 sitting Senators and a fifth of its House members have accepted contributions from the company.

Herzberg said the Blasting Advisory Board has sought meetings with the mining companies to no avail for years, during which the companies and trade advocacy groups like the Miami-Dade Limestone Production Association spread “disinformation,” including claims that slamming doors and kids jumping on beds damaged homes more than subterranean detonations.

The current setup and approach simply isn’t working, he said.

“We’ve never really spoken with the (Attorney General) or the Governor’s Office; we’ve always been focusing on the CFO’s Office (which, in its dual capacity as Fire Marshal, regulates and monitors the rock mining industry),” he said. “The law is structurally flawed. The mining industry is the only industry that has this protection. Why should it be protected unlike any other industry?”

3 comments

Hope

June 12, 2025 at 2:11 pm

Thank you for the article about agenda item 16 C coming before the council on Tuesday, June 17, 2925… We are blasting mad and we won’t take it any more!!!

Hope

June 12, 2025 at 2:12 pm

Thank you for the article about agenda item 16 C coming before the council on Tuesday, June 17, 2925… We are blasting mad and we won’t take it any more!!!

anjing

June 12, 2025 at 2:57 pm

I have fun with, lead to I discovered just what I was looking for.

You have ended my four day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye

Comments are closed.