If you want to better understand this year’s presidential election, you should read about a campaign almost 200 years old.

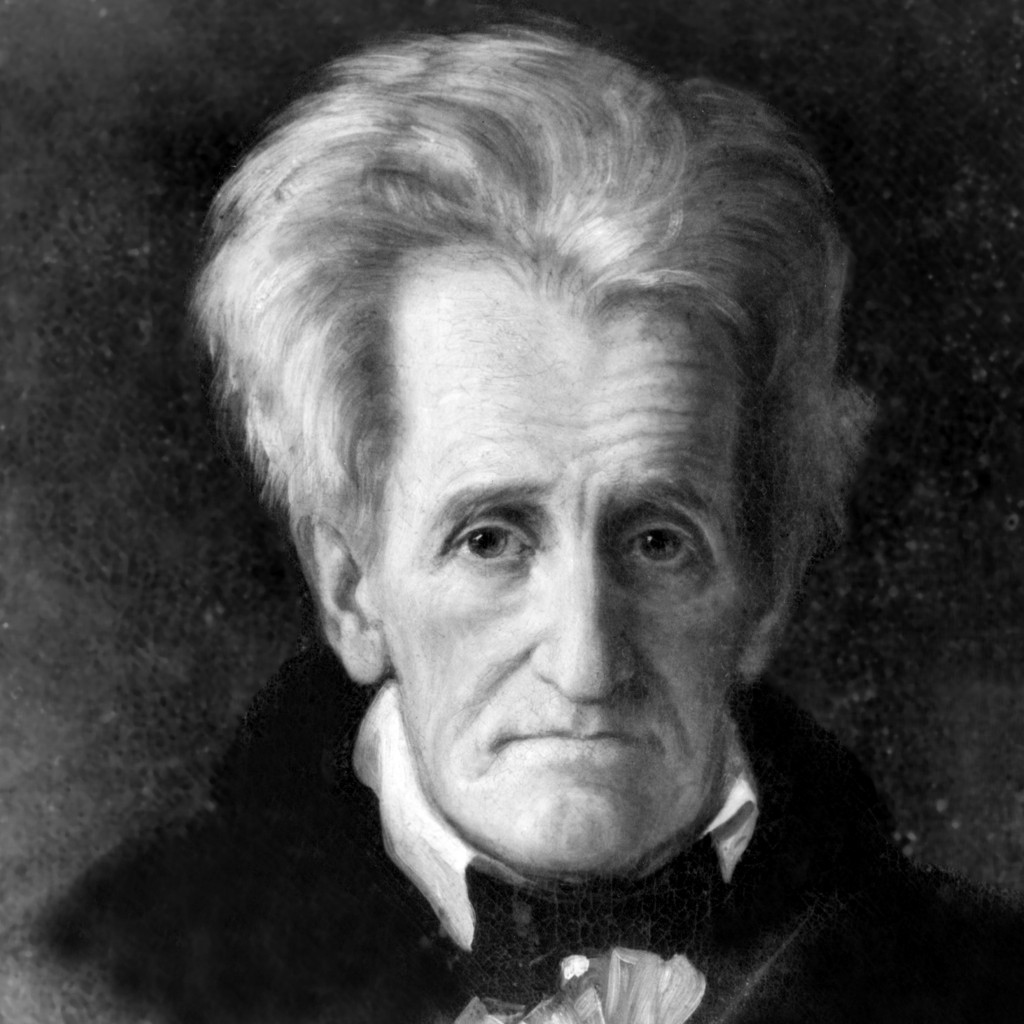

In 1828, Andrew Jackson became the first president of the United States who wasn’t a founding father or son of a founding father. Jackson rode a wave of anti-Washington sentiment all the way to the White House. His path was paved mainly by the actions of the House of Representatives in 1824.

In that election, Jackson won a plurality of the popular vote, but a deal cut between John Quincy Adams and Speaker of the House Henry Clay put Adams in the White House. Adams then repaid Clay by appointing him Secretary of State.

Although Jackson wouldn’t be sworn in for four more years, his campaign started that day. It became a four-year crusade against what he and his supporters called “a corrupt bargain” that stunted the people’s will.

Less than 50 years after the Revolutionary War ended, Jackson became the first candidate to spread an anti-Washington message. Gone were the young republic’s elder statesman revered even when they made mistakes. Now Washington’s second-generation power elites desperately tried to hold that power by nominating one of their own: John Quincy Adams, Harvard professor, U.S. senator, ambassador to England, secretary of state, and son of President John Adams.

He represented everything those elites wanted in a president, but by defying the will of the people they set up the first real presidential campaign.

The ’28 campaign was particularly nasty. Adams did everything from challenge Jackson’s literacy to calling him a “jackass.” Jackson responded famously by saying, “It’s a damn poor mind indeed that can’t think of at least two ways to spell any word.” Jackson also changed his campaign mascot to a donkey in a show of defiance still used today by the modern Democratic Party.

Every attack Adams and the elite threw at Jackson made him stronger. Even if the attacks were real and legitimate, the American electorate no longer trusted the messengers. Jackson won with 56 percent of the popular vote, almost double his 1824 total, and beat Adams by nearly 100 votes in the Electoral College.

They say “past is prologue” and if you look at this year’s presidential race, it’s easy to see the connections to the modern-day electorate. Americans have spent most of 40 years watching the decline of trust in the politicians who run this country. The perception is the elites in both parties have put their own will before that of the American people time after time after time, and have hoped no one would notice. Maybe they hoped just a state of apathy would allow them to continue in power.

That has changed.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump are running effectively on the same message: “Washington is broken, the system is rigged against you, and I’m going to fix it for all of us.”

Those two have shaken their parties’ systems to the core, and that should scare every party and elected official across the country.

No, the parties aren’t dead, but they’ll have to adapt.

It seems likely the Democrats will stem the tide one more time and get Hillary Clinton through to the convention on a combination of outsize support from African-Americans and Hispanics, and her almost insurmountable lead with so-called “Super Delegates.” The Republican nominee is almost certainly going to be Trump.

That should scare Democrats way more than it scares Republicans.

As Van Jones mused on CNN, he’s hearing from liberals who are trying to decide between Sanders and Trump. While ideologically that may seem strange, think about their shared message: “Washington is broken, the system is rigged against you, and I’m going to fix it for all of us.”

That’s not a message Clinton can carry into a general election. Americans don’t trust her and she’s been in the public eye so long that she’s now an embodiment of the Washington power elite.

Trump also may cut into Democrats’ core constituencies of left-wing anti-government types (think the voters who elected Jesse Ventura in Minnesota) and blue-collar workers who’ve lost jobs because of globalization and the U.S. manufacturing decline. That puts swing states such as Ohio, Pennsylvania and Florida squarely in the GOP’s sights, and puts historically blue states like Wisconsin, Minnesota and possibly even New York into play against Clinton.

Trump, though, will be able to carry that banner through to November. Although some Republicans claim they’ll never vote for Trump, their numbers are small. I’d argue that every time a GOP donor or consultant is quoted saying they’ll never vote for Trump, it only makes him stronger. It justifies the us-versus-them mentality.

Talk of the GOP establishment cutting deals for VP spots and Cabinet posts to consolidate the field against Trump strengthens him as well. It’s too late to stop him, and most Republican voters view such a deal as the “corrupt bargain” of 1824 that sealed John Quincy Adams’ fate.

Trump isn’t the war hero Jackson was, but he has tapped into the same disdain for the power elite that propelled Jackson to his 1828 electoral landslide. If things continue this way, I have a feeling Trump may win a similar victory in November.

The only question is, what does a Trump presidency do to America?