“I walked through the morgue and into the cooler yesterday. That slams life and its realities home to you.”

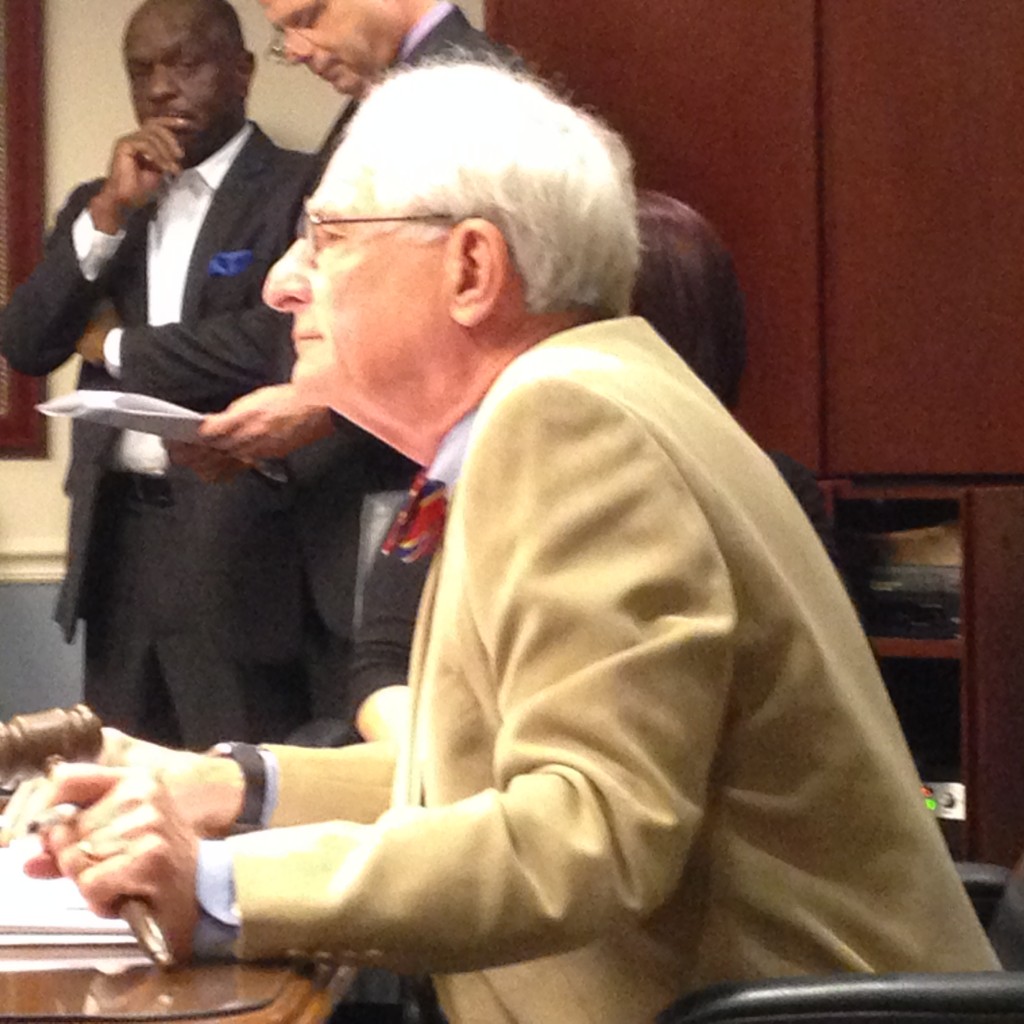

Councilman Bill Gulliford — a man who ensured, despite pushback from much of the Jacksonville City Council, that the overdose-racked Northeast Florida metropolis would attempt a pilot treatment program to deal with the wave of opioid overdose deaths in 2017 — was talking about the issue that has come to define the twilight of his long political career.

Or rather, he was talking about the people swept up in the issue: casualties to toxic pharmacological cocktails in the last week.

Two pregnant women: mothers perished as they carried life within them, and children who would never draw their first breath or see light outside the womb.

A medical student. And the daughter of a doctor.

A rhetorical question from Gulliford: “What’s the value of a life like that?”

Gulliford has seen it all: he arguably has as much “institutional knowledge” as anyone in Jacksonville politics. But the scale and ferocity of the current wave of drug deaths is like nothing else: “so horrifically bad … we’re plowing new ground with addiction.”

And answers are elusive thus far; when discussing the mothers who passed away, the Councilman wondered if they could have been Baker Acted if they had OD’ed before.

In fact, solving the problem of compelling people to accept treatment is one that preoccupies Gulliford: the opioid program is still beginning, and it will be months before success can be measured.

Treatment or jail, Gulliford said, could be a choice compelled by legislators down the road, if people prove to refuse treatment over the course of the program in Jacksonville.

“If 75 percent refuse,” Gulliford said, “we have a story to tell the Legislature.”

With cannabis becoming accepted in some jurisdictions as a non-lethal alternative to opioids, we asked Gulliford if perhaps that should be an option locally.

Gulliford questioned whether those addicted would be interested in cannabis, given that many of those who overdose on opioids first encountered them via pharmaceutical prescriptions.

“I don’t know if it would necessarily help,” Gulliford said, “but I’m all in for anything that might help.”

While some cities have decriminalized possession-level quantities of cannabis, Jacksonville thus far has not seen legislation to that end.

Gulliford also took issue with our contention that the treatment program was off to a “slow start,” noting that with six people having accepted treatment and 24 in contact with peer specialists, the program is doing “better than we expected” at launch.

The real test, however, will be after it’s in place for a few months.

One comment

James O'Donnell

January 14, 2018 at 11:54 am

Why is ‘institutional knowledge’ in quotation marks in the article?

Comments are closed.