Somewhere in a South Texas federal ICE detention center, a nephew of Dr. Eden’s Valentin awaits what, for all Haitians seeking asylum in the United States — and for their American relatives — must seem like impenetrable uncertainty for their fates.

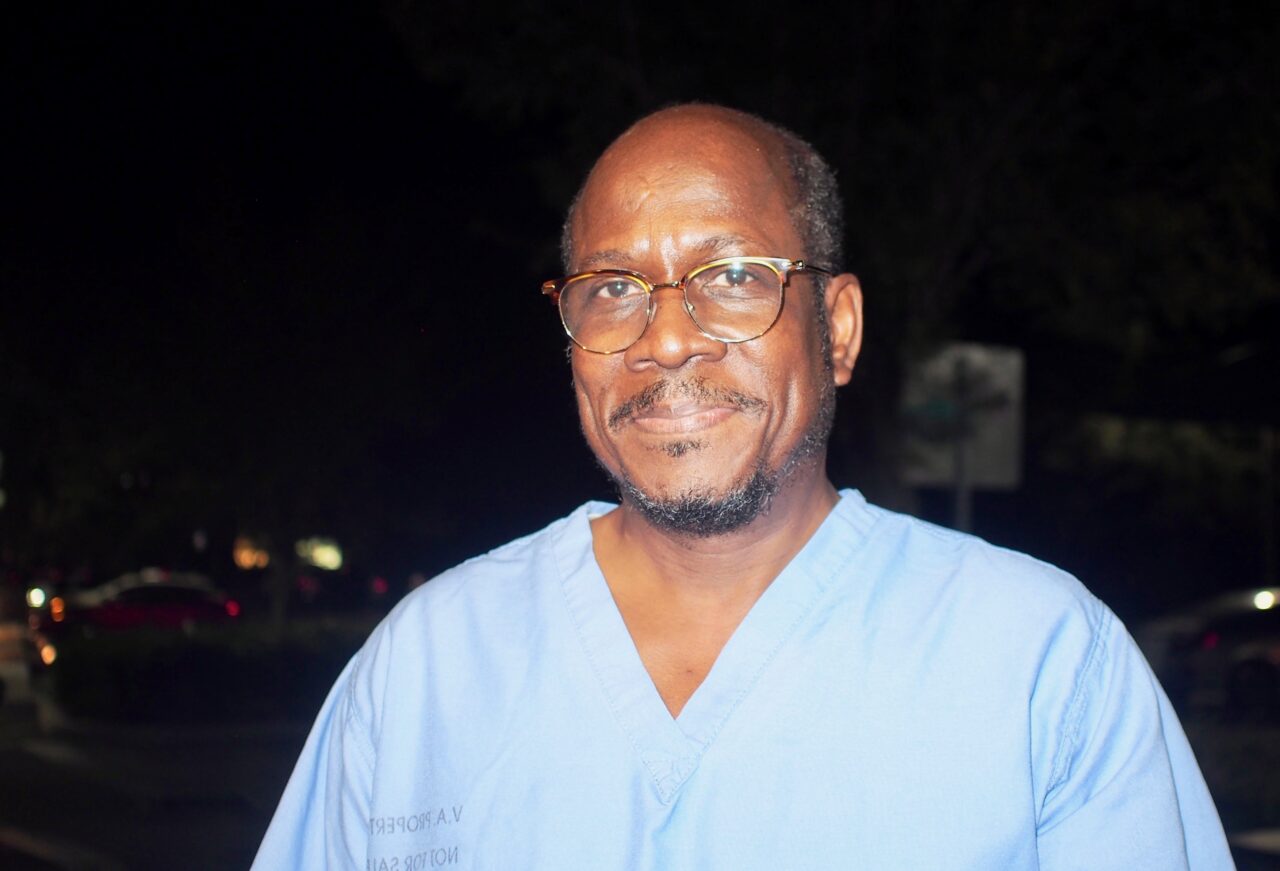

And yet, Valentin, an Oviedo internal medicine specialist, thinks his nephew, John Wesbert Alexandre, a 34-year-old construction worker who fled anarchy and despair in Haiti, is a lucky one, for now.

Since Alexandre was detained, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has flown thousands of Haitian refugees back to Haiti. Many of them were like Alexandre, trying to get to relatives in the United States. ICE allowed Alexandre to stay, albeit in what his uncle calls a prison.

“He’s young, and they might have favored the young people. Also, he’s by himself. He told me he (an immigration official) said, ‘That’s a guy with a good heart.’ Yeah, he’s got a good heart,” Valentin said.

Alexandre has been held in the South Texas Detention Complex in Piersall since Sept. 18. He was one of many thousands of Haitians whose treks from Haiti to the United States left them, after thousands of hard miles, much of it on foot, under a bridge in Del Rio, Texas, for weeks in September.

Valentin and his wife, Dr. Alexandra Alexis, also a Haitian American and an Orlando-area internal medicine doctor, are among thousands of Floridians who wait largely helplessly for U.S. immigration officials and courts to decide whether asylum claims will be accepted or whether detainees will be shipped, like thousands of others, back to Haiti.

As the world watches Haiti’s further decent into chaos, and as Americans debate whether the thousands of Haitians desperate to get into the United States are a humanitarian challenge or a menace, Haitian American Floridians like Valentin and Alexis experience the personal, family pain and uncertainty and anguish for their countrymen and women.

U.S. Census estimates say there are more than a half million Haitians in Florida, a mixture of American citizens like Valentin and Alexis, and refugees who are on hold in a variety of federal immigration programs. There are about as many Haitians in Florida as there are Wyomingites in Wyoming.

Alexandre has met with an American immigration lawyer and has been given paperwork to complete. He has been able to make occasional two- or three-minute phone calls to his uncle and aunt in Oviedo.

His uncle and aunt also have heard from his attorney. They have placed money in an account for him to buy things from the prison store and are filling out their own paperwork to sponsor him, providing documentation, paying his lawyer fees and waiting, but getting little information about his status or his chances, except that a preliminary hearing has been set in November.

“I do not know,” Valentin said of U.S. timetables for Alexandre and others there. “All I know is the conditions are real bad.”

And yet, Alexandre at least is still in the United States.

There were an estimated 17,000 Haitians under that bridge in Del Rio in September.

Most have been repatriated to Haiti. An estimated 7,000 are being held in U.S. custody, some released directly to family, and some in places like the South Texas Detention Complex, said Krystina François, executive director of Miami-Dade County’s Office of New Americans, one of the few state or local government agencies explicitly focused on aiding Haitian immigrants.

“It’s a very haphazard process at the moment with no clear guidance we can give to the community,” François said.

She said there is no available information on how many Haitians have been released to sponsoring relatives or how many more might be after hearings. Her office, she said, has provided assistance to many who’ve been released in Miami-Dade County, but those are only Haitians who have reached out, seeking assistance.

“We don’t necessarily have a number for folks who were able to successfully connect with a family and are getting their support. We are dealing with folks who have fallen through the cracks,” she said.

Those in detention get no word on whether they could get released any time soon, she said.

“It is a very long process. Unfortunately, it’s also a very discretionary process. You can’t necessarily say that at Step 2 you’re going to be released, or at Step 10 you’re going to be released,” François said. “It could be you could undergo your entire three-year asylum application process in detention. It could be you could do your entire three-year asylum process at home with an ankle monitor or with regular ICE check-ins. It’s very discretionary.”

She noted a lot of the Haitians they work with have been traumatized, if not back home in Haiti, than on their journeys.

“We’re dealing with folks with a lot of trauma, who have gone through, just the physical journey impacting on your body. The violence. The sexual violence. The exploitation. The being out in the elements. It’s not like you’re backpacking,” she said. “And then you’re exposed to criminal elements who are trying to blackmail you.

“And so to then make it to the U.S. soil, and then to be further traumatized and abused, isolated, and all those things, just compounds the situation,” François continued. “You’re coming for reprieve and relief. And really people are coming for safety and security. Often you hear the economic argument. But honestly, these are people who are seeking their human rights, to live in dignity, and they feel they can find that in this country.”

Two immigration options once available for Haitians no longer are an option. The qualification period for Temporary Protected Status expired for Haitians in August. Deferred Enforced Departure, being used for Venezuelan refugees, among others, is not being offered to Haitians now. That leaves, for Haitians, Humanitarian Parole, which is a temporary status for refugees, such as Afghans, who might be eligible for other programs but have not had time to apply. Asylum is also an option.

Many Haitians contend racism plays a role in how Haitian immigrants are treated, especially politically, viewed as a possible criminal element before they are viewed as a humanitarian crisis.

“Just to even label folks that have been detained … as criminals is false,” François said. “They are following a legal process. And that process, even when it has to do with law enforcement, is a civil process, not a criminal process.”

Their homeland, Haiti, has been through a disastrous period: Earthquakes. Hurricanes. COVID-19. Presidential assassination. A government losing control. An already weak economy all but collapsing. Increasing lawlessness. Mass kidnappings.

Valentin first came to the United States to do his medical residency in 1993. He stayed, married, became a U.S. citizen, settled in Oviedo, raised a family, and worked in hospitals from Sanford to Orlando. He remains passionate about his old country.

“I’m really sad. It’s a really a sad situation to see,” he said. “The one time that I had cried for Haiti, that was when they had that earthquake 10 years ago, when they were taking all these bodies because almost 200,000 to 300,000 people died, and they were putting all these bodies that day in trucks, and they were sending them to a communal grave somewhere. That was terrible for me.

“I cried again in that situation to see all those people under that bridge,” he added.