Miami Beach Commissioner Alex Fernandez is sounding the alarm about legislation he says could “irreparably harm” the city’s cultural and architectural composition by opening it up to unrestrained redevelopment.

He’s asking for the measure to be amended with “reasonable language” to mitigate the potential harm he says it could bring.

The bill, SB 1346 by Miami Springs Republican Sen. Bryan Ávila, has been quietly advancing this year amid a wave of attention-grabbing culture war measures. Along with its House analogue (HB 1317), the measure has just one more committee stop left.

SB 1346, dubbed the “Resiliency and Safe Structures Act,” would allow private developers to demolish buildings in high-hazard coastal areas, including recognized historic sites, with limited interference by local governments.

The buildings would either have to be:

— Located within a half-mile of the coastline, inside designated FEMA flood zones and nonconforming with requirements for new construction issued by the National Flood Insurance Program.

— Determined to be unsafe by a local building official.

— Ordered to be demolished by the local government that has jurisdiction over the property.

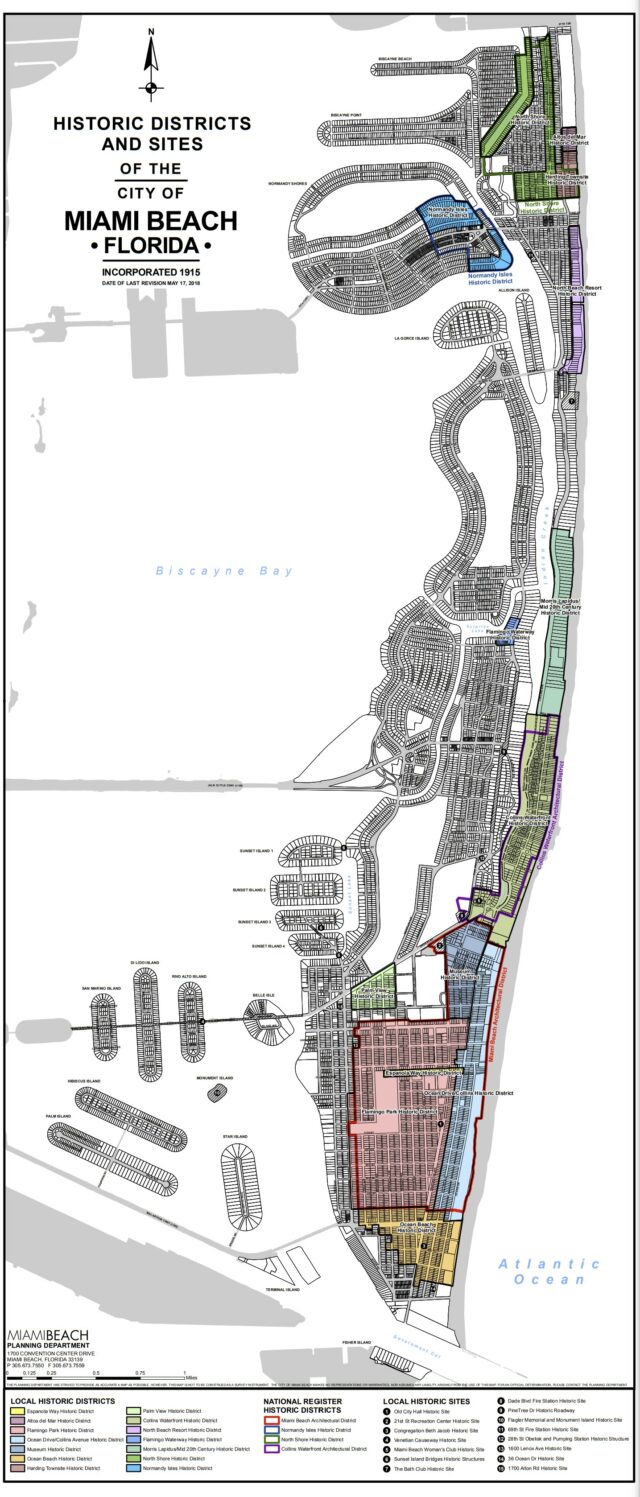

Most of Miami Beach is inside those flood zones, Fernandez noted, including an enormous share of the city’s historic assets.

After tearing the building down, developers would automatically be authorized to build a new structure on the site at the maximum height and density for which the area is zoned. Local governments would otherwise have little to no say in what the building looks like, including whether it’s a replication of the original structure.

That would undo an ordinance the Miami Beach Commission passed Dec. 14, which created a presumption that historic properties demolished due to neglect would be replicated.

In a Monday letter to Ávila, Fernandez warned that while the measure will bring “several determinantal effects” to more than 80 communities statewide with historic districts and sites, it will cause disproportionate damage to Miami Beach, which as Miami-Dade County’s fourth-oldest municipality is packed with notable buildings.

“I respectfully urge you to please reconsider eliminating the city’s ability to protect historic and architecturally significant structures,” Fernandez wrote. He noted that the city’s ability to set design, height and square footage requirements on replacement construction in the city helps to protect property owners who “paid a premium” to invest in historic districts based on those local powers.

“Allowing incompatible new buildings out of scale and out of character with the surrounding properties will ultimately negatively impact the value of adjacent historic properties.”

Fernandez also expressed concern that the bill could incentivize some property owners to deliberately neglect their buildings in order to profit from redevelopment.

“This will likely cause an increase in crime, vagrancy, vandalism, and trespassing, significantly degrading the quality of life for nearby residents, businesses, and visitors,” he wrote.

While the bill includes protections against demolition if it is determined that razing a building poses a threat to public safety and exemptions for single-family homes and sites on the National Register of Historic Places, Fernandez said there are still more than 2,600 buildings identified in the city’s historic preservation regulations that the bill would imperil.

Among them: the Soho House, Raleigh Miami Beach, Lincoln Theater, Eden Roc, Betsy Hotel, Casablanca Hotel, Versailles Hotel, Shore Club, Park Central Hotel, Essex House, Delano Hotel, Ritz Plaza, numerous buildings on Lincoln Road, the former Versace Mansion, all of Española Way, nearly every building on Ocean Drive and in the Art Deco Historic District, and many others.

Just eight sites — the Beth Jacob Social Hall and Congregation, Fontainebleau, Venetian Causeway, Ocean Spray Hotel, Cadillac Hotel, Giller Building, Lincoln Road Mall and North Beach Bandshell — are on the national register, city staff told Florida Politics.

“Our historic districts are internationally recognized and celebrated,” Fernandez wrote. “The loss of historic buildings will irreparably harm the cultural and architectural identity of Miami Beach resulting in a decrease in heritage and cultural tourism negatively impacting the regional economy.”

He added that permitting developers to construct as tall and big a structure as is allowed under an area’s zoning without allowing input from residents or city officials would give rise to projects “not consistent with the surrounding architecture within a historic district.”

“If passed,” he wrote, “this bill will preempt the will of the voters.”

SB 1346 and HB 1317 are among nearly 60 bills filed this Legislative Session seeking to wrest more control of local regulatory oversight from counties and cities across Florida. Some, including a measure banning local governments from enacting rent controls, even in declared states of emergency, have already received Gov. Ron DeSantis’ signature. Others, including a bill that would allow businesses to sue local governments to stop the enforcement of ordinances they deem “arbitrary or unreasonable,” are close to passing through the Legislature.

In its pre-Session briefing materials, 1000 Friends of Florida, a smart-growth advocacy group, described this year’s wave of preemption legislation as the “‘Session of Sprawl’ — the worst blow to sound community planning in more than a decade.”

The bill comes nearly two years after the collapse of Champlain Towers South, a 12-story condominium in the coastal town of Surfside that crumbled June 24, 2021, killing 98 people and igniting debate over building safety reform.

In June 2022, Florida lawmakers passed a law raising inspection and upkeep requirements, with added strictures for structures within three miles of the coast. Just two months earlier, the neighboring city of North Miami Beach evacuated residents from a five-story apartment building after officials deemed it “structurally unsound” during its 50-year recertification process.

Ávila did not respond immediately to a request for comment. As of 5:45 p.m. Wednesday, Fernandez said he has not yet heard back.

One comment

Arnold Becker

April 14, 2023 at 10:34 am

Alex Fernandez says the bill is “eliminating the city’s ability to protect historic and architecturally significant structures”.

Did Mr Fernandez think of:

a) financially incentivizing property owners to preserve?

b) purchasing the property and thus gain a personal right to decide if he wants it to be preserved?

Why does Mr Fernandez believe property owners rights should be infringed upon? There are other alternatives for him to consider.

Stating “eliminating the city’s ability” is far from being the truth.

Comments are closed.