Florida’s twice-updated Live Local Act is delivering affordable units and faster approvals, but not for a major category of renters it promised to help.

A new report from Florida TaxWatch says the 2-year-old law is falling short for “missing middle” renters — households that earn too much to qualify for affordable housing subsidies, but not enough to comfortably pay market rents in their area.

In Florida, that generally means households earning roughly 80% to 120% of the area median income (AMI).

The nonprofit, nonpartisan watchdog group says a major problem with the legislation is that its main incentive to help “missing middle” renters — a 75% property tax exemption for 80% to 120% AMI rentals — can be opted out of by eligible local governments.

Thirty-four of 49 counties eligible to opt out of the exemption this year have done so, citing the risk of revenue loss.

The legislation also doesn’t provide for pass-through to tenants, meaning landlords receiving tax breaks don’t have to lower rents. And many lenders ignore the exemption at underwriting, Florida TaxWatch found, because it kicks in only after a development’s completion, reducing the project’s feasibility.

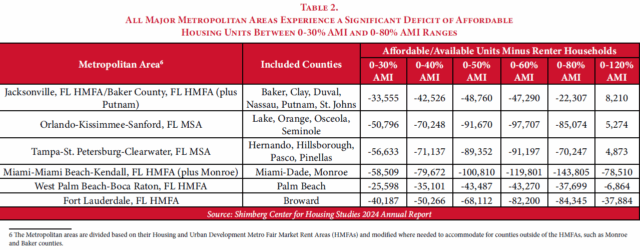

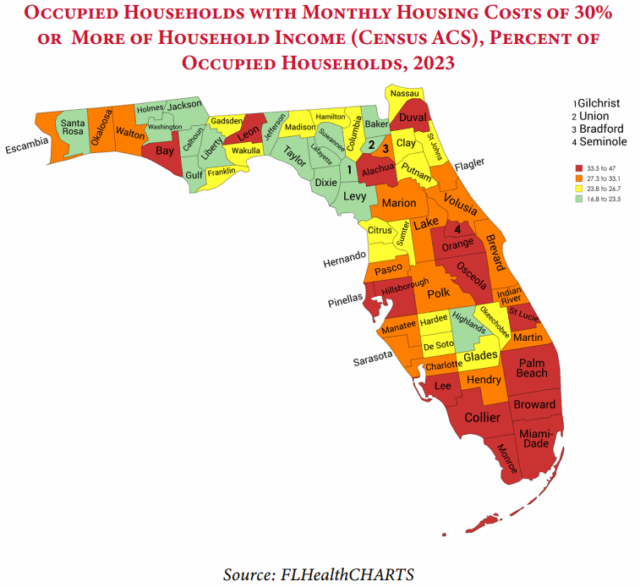

Florida TaxWatch found that 35% of Sunshine State households were cost-burdened in 2022, meaning they spent more than 30% of their income on housing and related costs. By 2024, the state was short more than 323,000 affordable units for households at up to 30% AMI, and in 16 counties, at least a third of households are cost-burdened.

“As the 2026 Legislative Session approaches, Florida TaxWatch urges legislators to continue to work with stakeholders to pursue measures to address the provision of affordable housing, especially for the missing middle,” Florida TaxWatch Vice President and General Counsel Jeff Kottkamp said in a statement.

“These are our teachers, firefighters, police, and other professionals who cannot afford to live near where they work.”

Sponsored by Sen. Alexis Calatayud and Reps. Demi Busatta and Vicki Lopez, all Miami-Dade County Republicans, the Live Local Act passed in 2023 and was updated in 2024 and 2025 to address Florida’s growing demand for affordable housing.

Among other things, it provides developers with financial and regulatory incentives to build more housing units, requires local governments to prioritize affordable housing development, streamlines the approval process and mandates that a substantial portion of new housing units whose development benefited from Live Local be available to a wide range of income levels.

The measure also prohibits local governments from imposing rent controls, permits housing development on land owned by religious institutions and requires local governments to reduce parking requirements for transit-adjacent projects.

Since the law went into effect, 3,171 affordable units across 23 Florida properties have been added. Massive mixed-use projects served by transit are leading the way forward.

In Orange County, Catchlight Crossings by Wendover Housing Partners is bringing 1,000 units of which 600 will be set aside for 30% to 60% AMI households and 400 will serve the “missing middle.”

In Miami-Dade, the recently approved HueHub will deliver 4,032 units — the largest Live Local project to date — in the unincorporated West Little River area with substantial workforce set-asides. Another project in Midtown Miami proposes 598 apartments, with 40% reserved for households at 120% AMI or lower.

So Live Local is indeed “moving units,” Florida TaxWatch says, but still not at a fast enough pace to adequately serve “missing middle” households.

To do so, the group’s report calls for additional state incentives and more consistent local implementation, including:

— Creating a state corporate income tax credit for homebuilders that produce attainable single-family homes.

— A state low-income housing tax credit for rental properties to augment the federal credit.

— Providing tax credits to projects that adapt existing structures, including historic properties (a recommendation sure to rankle preservationists who fought similar provisions in Live Local’s 2025 update).

— Encouraging uniform administrative approvals and discouraging retroactive local code changes that derail qualifying projects.

— Maintaining and enforcing expedited litigation timelines and public reporting.

Live Local has drawn ample criticism over the past two years. In a June column, the TC Palm editorial board lambasted the measure as “the mother of all unfunded mandates” because it erodes home rule and forces local governments to handle growth impacts without new revenue while developers get state-backed zoning advantages.

A lengthy report the Palm Beach Post published the same month highlights how loopholes in the law and local preemption let developers build pricier “workforce” units without ensuring true affordability, which is what prompts many jurisdictions to opt out of the 75% “missing middle” tax break.

Others — including industry voices like the Florida Housing Coalition, Live Local’s sponsors and former Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, who oversaw its initial passage — argue the updated framework is essential to cutting red tape, channeling capital and making a dent in Florida’s short affordable housing supply.

“It’s working in many, many places,” Passidomo told the Post, adding that county and city officials must step up to maximize the legislation’s efficiency and efficacy. “It’s all about leadership on a local level.”

One comment

LexT

August 13, 2025 at 7:56 am

The Legislature has identified the problem, but they really have not identified the solution. What they need to do is force each county to designate a percentage of its upland area as high-density, akin to the missing middle. Give the Counties and cities the ability to decide where to put them, but make them make decisions. Local governments can make these choices better if the choice is forced upon them.

Comments are closed.