For good or ill, the world the today’s kindergartners will graduate into demands more of them than it did of their parents.

Florida’s antidote to that was supposed to be free preschool for every 4-year-old in the state.

The voter-approved initiative that launched voluntary prekindergarten said the program should be “voluntary, high quality, free and delivered according to professionally accepted standards.”

So far, the adults have been the ones struggling to keep up their end of the bargain.

— Funding for VPK is less now in real dollars than it was in 2005 when the program began.

— The program has only ever been funded to pay for three hours a day of instruction time.

— Consensus on how to measure “quality” has been hard to come by.

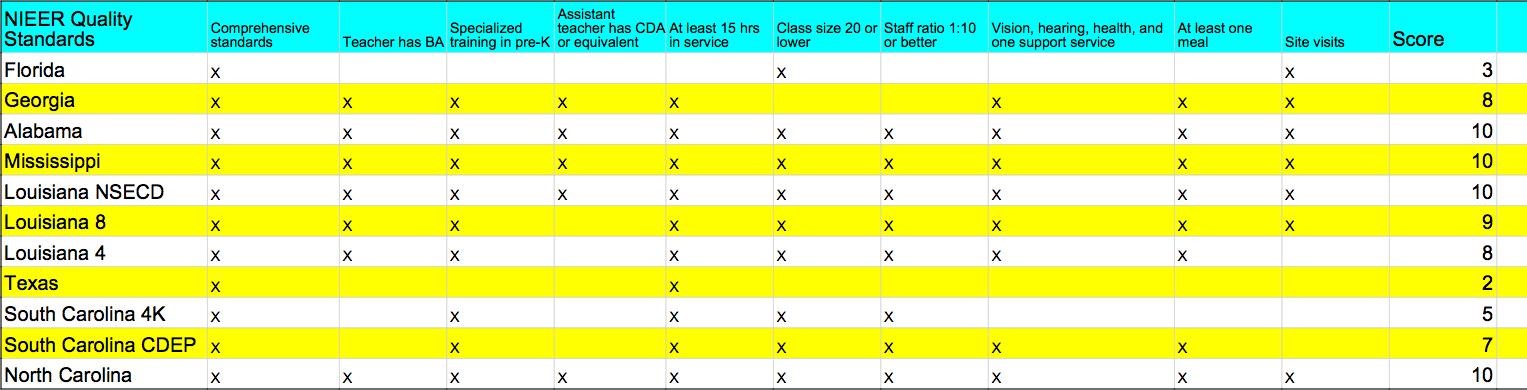

The National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University has been using reports on “The State of Preschool” since 2003.

On its quality measures, Florida earns a 3 out of 10, one of the lowest scores in the South.

State officials note that NIEER’s quality standards are “inputs” — teacher training, student-staff ratio, health and service screenings offered. It doesn’t measure the quality of interaction between the adult in the classroom and the 4-year-olds in her care.

Nor does it measure how ready for school those children are once they get to kindergarten.

Florida used to gauge kindergarten readiness by evaluating the early literacy and developmental and social skills of 5-year-olds.

But that evaluation — which also was used to measure the effectiveness of individual VPK providers — has been altered multiple times, meaning readiness rates have not been issued since 2013.

So much for tracking the “outputs” reliably over time.

Into the breach has stepped the Early Learning Coalition of Escambia County. The “Stars Over Escambia” program is being rolled out among the 165 child care providers contracted with the Coalition.

The Coalition is the financial gatekeeper for two programs meant to boost early learning outcomes:

— School Readiness: A program that pays for subsidized child care for children ages 0 to 13 as long as the parent works at least 20 hours a week and makes less than 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. For example, a family of four with an income of $36,375 is eligible for the program.

This year, Escambia County got $13.6 million for School Readiness from the state. For next year, the amount is the same. There are just under 3,000 children in Escambia County in the School Readiness program.

— VPK: Escambia County’s funding for next year is about $5.4 million. This school year, 2,080 4-year-olds are enrolled in VPK in Escambia County; 500 attend a school district run VPK. The rest attend at private centers. There are 85 contracted VPK providers in Escambia County.

Stars Over Escambia has lots of things going for it. It tracks the “inputs” like staff development, education and training of teachers. It requires a center to use an assessment tool called Teaching Strategies Gold to earn its highest ratings — one that aims to combine the social, emotional, and developmental milestones a child should meet with the early language and number skills they’ll need for school later on.

It rewards centers that make sure art, outdoor time and “messy play” are still import parts of the preschool day.

My favorite part — it tries to make sure parents are brought into the fold.

To earn the system’s highest marks, a center must engage parents.

In writing. Face to face. In family conferences. By offering family education and outreach tools. By giving parents a voice in how the center is run through an advisory board.

Measuring how engaged a parent is can be tough. Short of going into someone’s home to watch how they talk with, play with and treat their child, it’s hard to know what the metric for that is.

But making child care centers track which tools and supports they offer families — and by tying it to a rating of quality — is a place to start.

The Stars program is voluntary. No bonus or stipend comes with a three- or four-star rating.

There are many reasons that centers give for not participating in the existing, voluntary state-level efforts meant to track quality.

Some objections are based on religion. Some bristle at the idea of state influence over how children are assessed. Some don’t find the effort required for the Gold Seal Quality Program, for example, is worth it because state funding doesn’t keep pace with the cost of doing business.

Peer pressure to follow the program, the desire to be recognized for doing more than just what the letter of the law requires, will have to be the motivating factors.

Here’s hoping that more adults find the internal motivation to follow the Stars.

It’s the first step on a long journey of ensuring all of Escambia County’s children get the chance they deserve to follow their dreams — wherever they lead.

___

Shannon Nickinson is a fellow at the Studer Community Institute, a Pensacola nonprofit dedicated to using journalistic strategies to improve the quality of life in the community, and is editor of www.studeri.org. Follow her on Twitter @snickinson.