Tuesday was budget night for the Jacksonville City Council. Arguably, the most interesting segment of the whole evening came at the very end, when Councilman Scott Wilson proposed a stunning floor amendment: de-appropriating $2.1 million from the Jacksonville Journey program — 50 percent of its funding — due to a lack of crime data provided for the 10 zip codes targeted.

The motion failed. If it had passed, the Journey would have been fully funded for six months, giving the program time to marshal its data and make the case for its continuance as it is currently.

Journey programs target the Northside and Northwest Jacksonville; across the river from Wilson’s district on the Southside, which includes myriad neighborhoods that time and economic incentives have passed by.

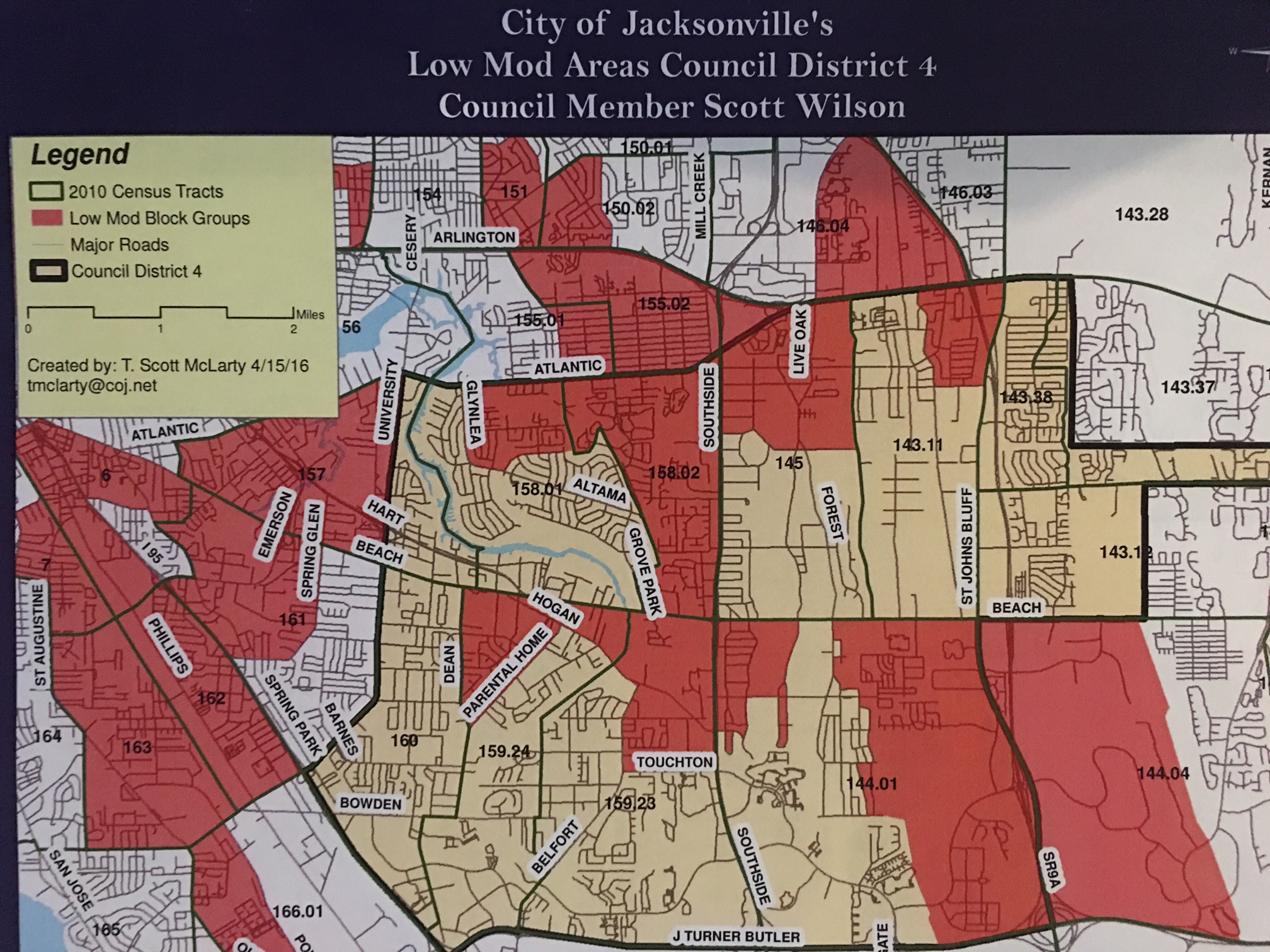

Wilson’s contention: that parts of zip codes in his district (32216 and 32256) have more violent crime than areas targeted by the Jacksonville Journey, such as 32205 (which includes some crime-ridden parts of the Westside but also the tony enclaves of Avondale and Ortega) and 32202 (which has crime stats artificially inflated by incidents at public buildings, such as the pre-trial detention center and EverBank Field, where a game experience has been compared to pre-trial detention by some jaundiced observers).

The hour was late when Wilson made his play against over $2 million in the Journey budget, and the discourse was heated.

The goal of the conditional removal of allocation, Wilson said, would have been to “give us more time to evaluate it.”

Wilson’s frustration: he had wanted crime stats for areas in his district to do a direct comparison with areas getting Journey funding.

Furthermore, he had requested those stats originally in March. Ironically, given the Journey’s avowedly data-driven approach, these stats weren’t provided to Wilson’s satisfaction.

Instead, they were only offered on the district level, which didn’t tell the story he felt needed to be told.

After months of trying and failing to get meaningful data, Wilson found an important ally on budget night: Council President Lori Boyer wanted to know when useful information could be provided.

“We don’t want a generic ‘we’ll work on it.’ Give me a time frame … how did you select the 10 zip codes?,” Boyer asked Community Affairs Director Charles Moreland, adding a pointed question regarding the data: “When are you going to come back and get more granular?”

Moreland vowed to bring more refined data within 30 days.

****

Wilson has become something of a crusader when it comes to how the city uses data; he has taken aim also at how data is used for economic incentives.

Jacksonville offers competitive economic incentives for businesses operating in underperforming census tracts, where especially high unemployment and low income are the criteria.

Wilson, during the subcommittee that formulated this policy, noted that when the metrics were more robust, including measures such as high school graduation rates, many Southside neighborhoods were in peril.

“Windy Hill is the poorest neighborhood on the Southside … Sandalwood is not what it once was,” Wilson said.

Also on the brink: Parental Home Road. Hogan Road. Grove Park. The northern stretch of Touchton. Windy Hill.

There is a stereotype of the Southside of Jacksonville promulgated largely by those who are never on the ground there, who never see the strip malls hovering around 50 percent capacity, who never see the sad-faced mothers walking their kids on the cracked sidewalks, who never consider the crime and the decrepitude.

They seem to believe those neighborhoods are stable, like they might have been in 1974 or 1984.

But Jacksonville has changed. And big chunks of the Southside have “evolved” also, from ownership neighborhoods, to neighborhoods dominated by rental houses, many owned by absentee landlords.

And just as anywhere else, where poverty rises, crime spikes.

****

After the council meeting wrapped, Wilson discussed his motivations for his floor amendment, which he told media he didn’t go into the evening expecting to make.

“If I ask for something,” Wilson said about the data, “I should be able to review it.”

Wilson called the Journey a “great program,” adding he never wanted to stop funding, but to use data more meaningfully to address problems.

In short, his critique of the zip code data being used for the Journey allocations was of a piece with the use of census tracts, rather than blocks, for economic development incentives and Community Development Block Grants.

When asked if the zip code allocation of funds was political in nature by Florida Politics (a politicization that sees at least one well-connected preacher benefiting from Journey programs), Wilson disagreed.

“I don’t think it’s political,” Wilson said. “I just don’t think zip codes are the way to [measure] violent crime.”

Wilson mentioned the Block by Block study as a “great place to start” in analyzing the true stresses of neighborhoods.

The Block by Block study looked at neighborhoods not in a homogenous way, but as a mosaic, one with different characteristics sometimes from one block to the next.